In the Hollywood Theater, a bustle of side conversations, the crinkling of popcorn and the fizzle of pop fill the air. It’s my first Wes Anderson film in the theaters. As I lean back in the creaky red seat, dust appears, lit sporadically through the projection light. I see the operator peer through the window to the film room, and I realize it’s been a year since I last experienced a film on the big screen.

I missed the feeling of the collective viewing, reactions in real-time with complete strangers. As the buzz of the Hollywood wanes and the lights dim, I anticipate “The French Dispatch” on the night of its release in Portland.

The eponymous French Dispatch magazine is based on the early operations of the New Yorker. The iconic magazine is present in all aspects of “The French Dispatch’s” function: the focal storyboard, the ode to the city through the cover art, even adaptations of real-life stories. The New Yorker’s momentous impact on New York City is reflected in the symbiotic relationship between the French Dispatch and the mid-20th-century fictional city of Ennui. The publication writes stories on the rumors and the latest events of the city to ensure all residents are acquainted with the heart of Ennui. Each French Dispatch writer is inspired by actual journalists from the New Yorker, emulating the bustling continuity of a magazine publication.

“The French Dispatch” is Anderson’s love letter to French cinema. French New Wave films are spontaneous and personal, often utilizing handheld camera techniques and seemingly unrelated storylines that are only thematically-linked. Not limited by the boundaries of a traditional plot, they can experiment with abnormal flow and transition. Fragments of the New Wave lay the foundation of the film.

Even though this is Anderson’s most experimental film to date, his signature style effortlessly shines through “The French Dispatch.” Anderson’s films are detailed in symmetrical and pastel storybook perfection, ruled by idiosyncratic characters and vivacious dialogue. In “The French Dispatch,” his peculiar directing is radiant. It’s present in the meticulous camera positions, aesthetically sublime sets and humorous repetition like the continually referenced “No Crying” sign plastered on the wall of Howitzer Jr’s merciless office played by the incomparable Bill Murray.

Though Anderson is known for his mastery of artful storytelling, in “The French Dispatch” his use of various visual mediums can be overwhelming. Alone, the Tin Tin-inspired animation, still action shots, split screens, rotating sets, theatrical acts and the conventionality of black-and-white’s simplicity could have inspired awe in anyone. But, all the mediums intertwined become a whirlwind of a visual headache.

In the Dispatch’s final issue, “The Concrete Masterpiece,” strikes me the most. In black and white, a nude woman poses gracefully as a gruff man spattered with paint hides behind a canvas capturing her essence in a visual cacophony of pink. Contrary to my assumptions, the intrepid muse, Simone (Lea Seydoux) possesses all the control over the painter, Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro). Anderson elegantly disguises their true personas. Rosenthaler swiftly puts on a straitjacket, and Simone, a prison guard’s outfit. It closely resembles a scene in French New Wave film “Jules and Jim,” directed by the efficacious François Truffaut, where Catherine (the love interest) dresses masculine, drawing on a mustache to disguise herself for the day.

From the aerial shot of Simone and Rosenthaler atop a pile of clean laundry to the unlikely dynamics of the two, Anderson’s cinematic character choices in “The Concrete Masterpiece” enthrall me.

The remaining stories of “The French Dispatch’s” final issue include a history book of Ennui, a love story, a kidnapping and the pursuits of a chef.

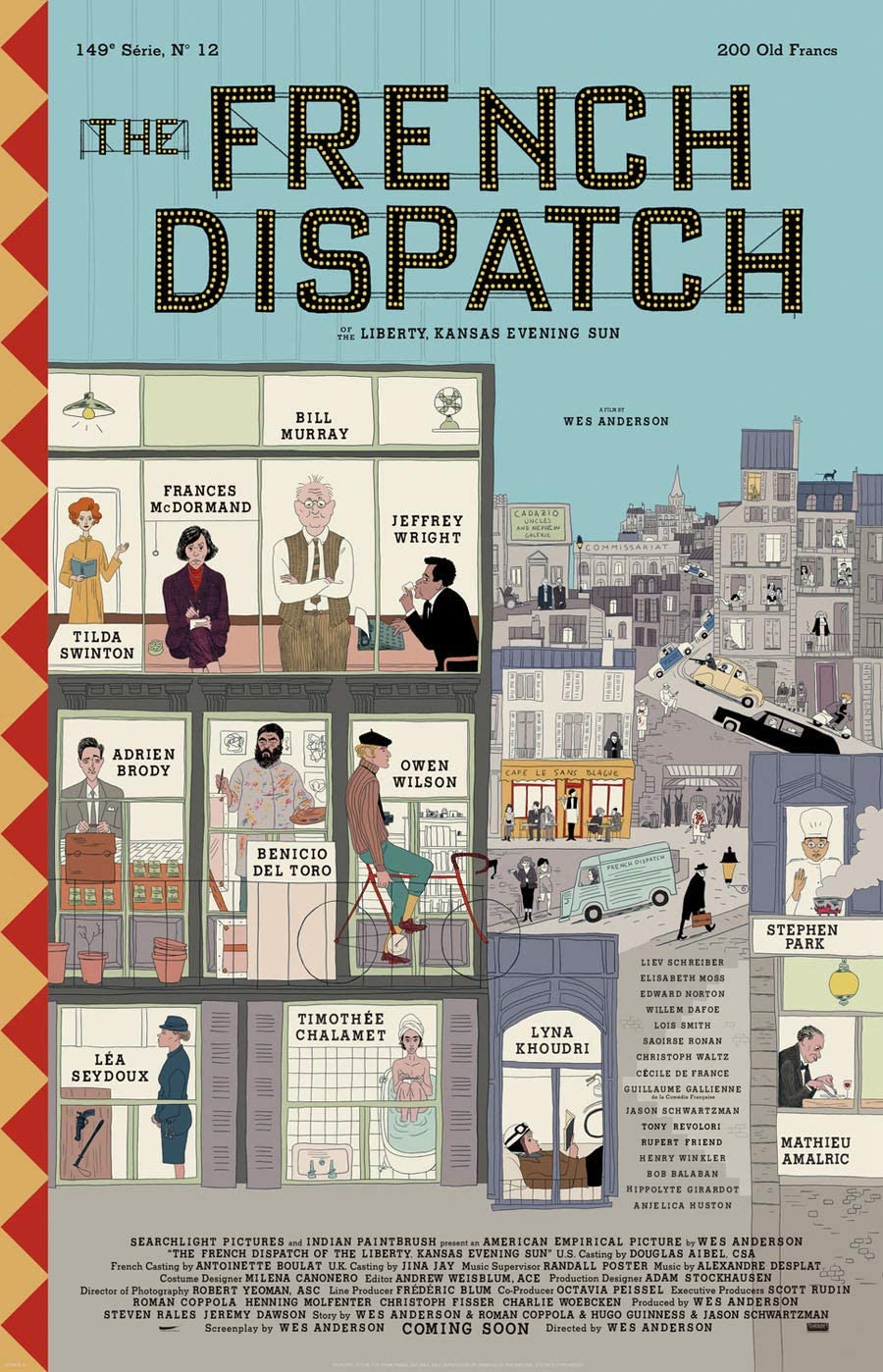

I heard in interviews that Anderson is driven by the connections he has with his actors. He casts the same group of people because he is purportedly shy. However, in one of his most stacked casts, with actors ranging from Benicio Del Toro to Frances McDormand, the struggle to balance every character is felt by the audience.

The thread that connects every piece of the visual magazine is the fictional French city of Ennui. But, with the rapid succession of each story, the theme shifts to chaos and spontaneity, which deserts me with no attachment to the characters’ lives.

However, in “The French Dispatch’s” spontaneity, there is a charming side to the chaotic nature of the stories of the Dispatch’s final issue. It is a treat to attend a film with the expectation of one story, but receive the gift of five.

I do not grant the characters of “The French Dispatch” enough credit—their odd sensibilities shape the film. As if the characters on screen emulate the strangers who pour out of the theater, I can picture the subjects and the writers returning home after their lives on screen conclude.

I believe Simone is at home basking in the company on her reconnection with her child. The French rebel girl is arguing just to argue. The Investigative reporter, Wright, is hunched over his desk, smoking a cigarette, ferociously solving the next riveting crime. Krementz is likely critiquing the appendix of a naivetes manifesto. And all the lonesome admirers, artists, punks, rascals, rebels, critics, lovers and friends that I witnessed depart the Hollywood are reveling in all “The French Dispatch’s” witty yet hurried glory.♦