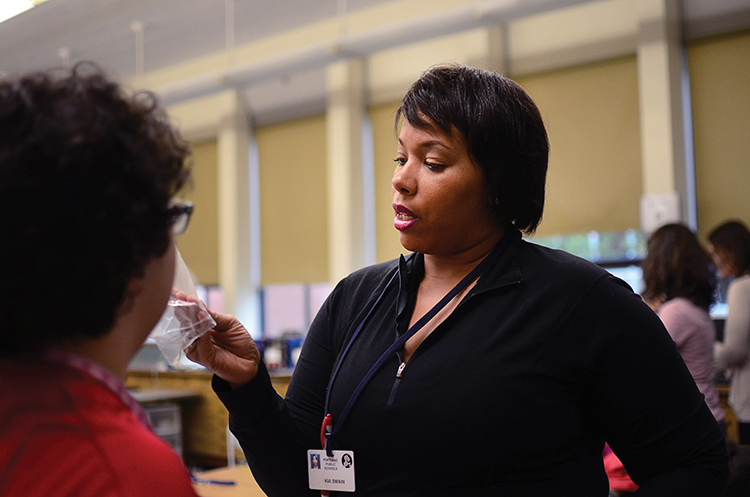

“Good morning sistas!” Kia Swain says as she turns up the dial on her portable speakers. She rolls up her sleeves, singing and dancing along to Mary J. Blige, while a few girls walk into room 209. A display of fruit, muffins, fried chicken, egg sandwiches and juice sits on a table in the middle of the room.

Outside the brightly lit classroom, the November sky is still dark. It’s 7 a.m. on a Thursday, and “Super Soul Conversations for Sistas” – a group for girls of color at Grant – commences. Swain makes her rounds to the girls as they settle in. “How has your week been going, sweetie?” she says to one girl. Her soft but affirming voice encourages the girls to open up.

She then makes her way to the front of the room with a paper fan in hand. For the next hour, their conversations, reflections and decompression create an important space for the girls.

“She has helped me so much,” says sophomore Jada Manns-Wadsworth, a student who participated in the group. “When we are in that room, we are sisters. And when we leave that room, we’re still all sisters. We all have each other’s backs.”

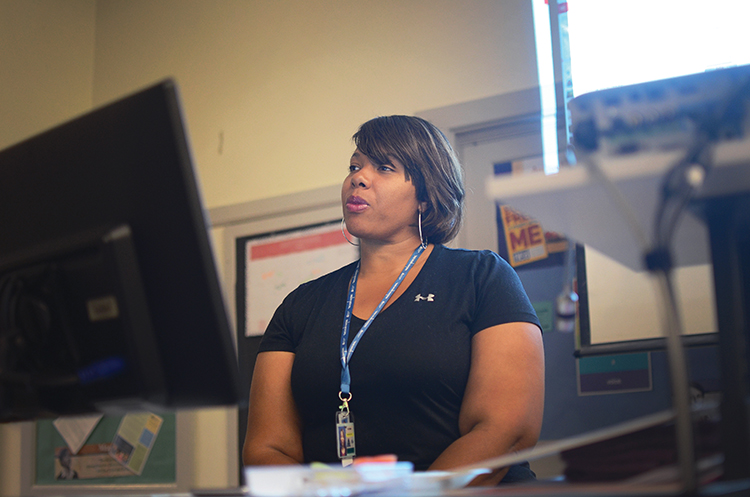

Currently, Swain works as a paraeducator at Grant, working with students with special needs. Her path to get there hasn’t been easy. Growing up with an absentee father and being the primary caretaker for her mentally ill mother, Swain wasn’t supported. And once she graduated high school, her rough childhood led to a string of domestic abuse and bad decisions.

Swain credits mentors who have stepped in along the way, and Oprah Winfrey’s talk show, as the forces that set her on a positive path. “It’s the best therapy I ever had in my life, and it’s free,” she says about “Oprah.”

After being hired at Grant in 2014, Swain stepped in as a mentor figure for girls of color and created “Super Soul Conversations for Sistas.”

“Kia has done a really good job of providing a space for young women of color,” says Grant Principal Carol Campbell, who has supported the group since it started.

By sharing her life experiences, Swain hopes to make a difference in students’ lives. “There’s a common theme and thread that we all share,” she says. “I wish I had a group like this when I was these girls’ age.”

Swain was born in Portland on January 6, 1974 to Moses and Sharon King as the youngest of four siblings. She grew up in a Jehovah’s Witness household in Northeast Portland and attended Applegate Elementary School in North Portland.

Her parents separated when she was in first grade, and her father left the family. She didn’t see or speak to him again until she was a sophomore in high school.

After her father left, Swain’s mother developed Schizoaffective disorder – a mental illness which caused her to lose control of reality. She could no longer take care of her children.

Swain clearly remembers the day she was taken away from her mother as an 8-year-old.

After a disagreement between Swain and her mother over which outfit to wear to school in the morning, Sharon King called her daughter home from school in the middle of the day. When Swain arrived at home, her mother was waiting with a switch – a small tree branch – in hand. She hit Swain repeatedly, leaving bloody welts and bruises. Moments later, Swain’s grandmother came to check on the house.

“I just remember the house was messy, the lights were turned off, no water, and I was not looking very good,” Swain says. “My grandmother took me at that point.”

Her grandmother was already struggling to take care of herself, so Swain didn’t have anyone to watch over her. Her neighbor, who she called Ms. Lewis, was one of the only people in her life that consistently checked in on her.

But that wasn’t enough. With the risk of being placed in foster care, her brother Wiley King, who was 20 years old, stepped in to raise her.

“I had to be a brother and a father at the same time,” said Wiley King in an interview before he passed away in February of this year.

Throughout elementary and middle school, Swain says she didn’t feel like she was seen. “Being a black girl, being raised in Northeast Portland, you’re not seen. You’re invisible,” she says. But she had to push forward.

When she entered high school, her mother was stable enough for Swain to move back in with her, although Swain still had to help be a caretaker. On top of the normal stressors of life in high school, Swain felt helpless.

“That was a very traumatic thing in my life. You’re going to school, and you have teachers that didn’t see me,” she says. “They didn’t know that I was struggling, and I definitely didn’t feel comfortable telling them.”

Eight months after graduating from Benson High School in 1992, where she received her Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA) license, Swain moved to Atlanta, Georgia to attend Clark Atlanta University. There, Swain became involved in an abusive relationship and dropped out of school after only one year.

Two years later, she decided it was time to move back to Portland to get away and help take care of her mother. But, her boyfriend moved as well. “He followed me here,” she says.

Then, in February of 1998, Swain gave birth to her first child, Eathen. Seven months later, she followed her boyfriend to Lima, Ohio. “I went to Ohio because of him. And even though he had abused me … I still went. I was misguided,” she says.

Less than a year later, Swain found herself running barefoot down the street one night to find help after being beaten by her boyfriend. She left her baby asleep in the house. “He almost killed me,” she says. She stopped at the first house she could find. “I remember knocking on a door, and this man came,” she recalls.

He saw the bruises on her face and took her in, giving her a warm blanket as she huddled in the corner of his kitchen. After calling the police, the man walked her outside to the police car. “Ma’am, you’re gonna be OK. You just need to get home,” he said to her.

That night, after retrieving her baby from the house, she called Wiley King. He heard the distress in her voice and immediately bought her a ticket for a flight home the next day.

She returned to Portland in 1999 with a one-year-old child, looking to decompress. “I came home, and was trying to feel good about myself again,” she says. “There was a time in my life when … I really wasn’t sure if I was even going to be living.”

In Portland, life remained difficult. “The childhood trauma I had been through with my mother, absentee father and just the instability of my life, then meeting a man that beats you,” says Swain. “I developed severe panic attacks for a while.”

One month after her return, she met the man who would become her husband, Christian Swain, as they were working out at Matt Dishman Community Center in Northeast Portland. They got married within the year.

In 2001, they had their first child Johnathen, and six years later gave birth to a daughter, Shelby. They have been together ever since.

Swain went on to study Human Services at Chemeka Community College in Salem. Despite the newfound stability in her life, Swain still felt like she hadn’t found her purpose.

What ultimately helped set Swain in the right direction was the past advice of her neighbor, Ms. Lewis.

“Asking me things like where I saw my life. Helping see things with a different perspective, helping me see myself,” she says of her neighbor. “And she was a big Oprah Winfrey fan. She said: ‘You should watch Oprah!’”

Since then Swain has looked to Winfrey’s talk show for advice on how to navigate life. Throughout the ongoing struggle of caring for her mother, she credits mentors like Winfrey and Ms. Lewis for turning her life around. “When somebody just shows some interest and … support, it can be transformative,” says Swain. Feeling the impact of mentors reaching out and caring inspired her to do the same.

At Roosevelt High School – where her husband worked from 2009 to 2016 – Swain found her passion. Christian Swain worked as the athletic director, campus security coordinator, head football coach and most recently, career coordinator, and even though she didn’t work there, Kia Swain was a common face in the community, cultivating relationships with students. They called her “Mama Kia,” her husband says.

At one point, he and Swain noticed an athlete struggling. “He just looked terrible. Looked like he was sleeping outside, looked like he hadn’t brushed his teeth in a month, dirty clothes,” Christian Swain says. The couple decided that they had to do something to give the student an opportunity to be successful. They let him stay in their home, as they would for many other kids during this time.

“We just constantly had a stream of kids living in our home,” says Kia Swain.

Swain found herself gravitating towards conversations with the football players’ girlfriends and other girls at the school. “Girls, especially girls of color, so much pressure is put upon us,” she says. She hoped the conversations and her stories would help the girls get through struggles they were facing in their own lives.

Swain was still working as a CNA but says she always wanted to be a teacher. So, in 2010 she was hired at Benson High School, working with students with special needs.

After working at Benson High School, Prescott Elementary School and Lifeworks Project Network – a program for women who dealt with substance abuse and health issues – she was hired at Grant High School in 2014 as a paraeducator.

But through working in schools, Swain noticed something that didn’t sit easy. “The push in PPS (Portland Public Schools) is African-American boys, they’re failing. But you cannot deal with black boys without dealing with black girls,” she says.

When she got the job at Grant, she knew that she had a responsibility to continue having conversations with girls of color.

In Spring of 2016 she formed the group “Super Soul Conversations for Sistas,” named after Oprah Winfrey’s “Super Soul Sunday” talk show. “Watching her have all these conversations, it helped me to grow, as a mother, as a woman, as a black woman. So I just said, ‘OK, let me do it at Grant. Let me just go ahead and do what I’ve always been doing and do it here,’” she says.

Designed specifically for young women of color, the group was an opportunity for students to openly share and express themselves in hopes of providing a support system within the school.

“I feel like it changes us in a positive way … It makes you feel like you’re not alone,” says junior Jai’aja Winchester, who started attending meetings from the beginning.

At the end of last school year, Swain left Grant and decided to take a position at Multnomah Education Service District, working as the Lead Transition Specialist. But Swain only stayed until November of 2016, when she resigned from the position due to differences in opinion and work methods. She returned to Grant as a paraeducator and stayed with the group throughout it all. Swain couldn’t walk away from the relationships she’d fostered with kids at the school.

The development of the group came at a time of rising conversations around race. Starting in March of 2016, Grant has hosted school wide discussions in the wake of racist incidents at the school. And after the police killings of unarmed black men and boys such as Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Tamir Rice, discussions about race have also been at the forefront of national media.

Along with topics of cultural appropriation, colorism and more, young people are experiencing the impacts of these current events – and the girls point to this group as a place of decompression.

“It’s made me overcome bullying and teasing,” says Manns-Wadsworth of the group. “There’s a lot of stereotypes about women of color. I always thought there could never be a change, but … no. I can be the change one day.”

Although the group hasn’t met in recent months, in part because of the recent loss of her brother, Wiley King, Swain is devoted to creating a space for “Super Soul Conversations for Sistas” in the future. Every day, she still talks to girls from the group in the halls.

“I would like to restart the group. But right now … I’m still grieving,” she says after her brother’s death. “I love the relationship that I foster with those ladies.”

Swain hopes her story encourages the girls to be whoever they want to be. Her past struggles have allowed her to be selfless toward others.

“She used the dysfunctional situation that we came out of … as a motivating factor in her life,” said Wiley King.

“You will have obstacles to overcome, you’ll have challenges in life, you’ll have love, you’ll have loss, you’ll have death, you will have disappointments,” says Swain. But through everything she always holds out hope. “It is possible to overcome and thrive through anything.” ◆