The sun has just set, and darkness is beginning to fill the sky when Grant senior Sidney Jones, then 13 years old, prepares to run away from home.

Without hesitation, she grabs a thumbtack that’s jammed into her wall and proceeds to quietly cut a hole out of her window screen. She then climbs down the drain pipe from the second floor of her house and makes her way to the street.

With only a few articles of clothing and her stuffed panda in her backpack, she takes her shoes off – feeling more stable with her bare feet on the pavement – and walks off into the dusk to find safety at a friend’s house. There, they take photos of the places where her mother had bitten her earlier that day.

Coming from an abusive household, Jones’ only option was to find refuge away from home. Throughout the majority of her life, depression, anxiety and a hostile living situation controlled her well-being. She has attempted to take her own life multiple times because of it.

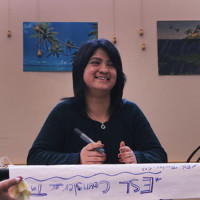

Finishing high school and going to college, was never a priority for Jones. But with the support of her best friend and his family, she got back on her feet. Jones is now on track to graduate and attend a four-year college.

As a senior, she has turned her rough past into motivation for others. Jones helps with the Reconnecting Youth group at Grant, a counseling group to support students on their personal goals related to emotional management, drug and alcohol control and school achievement. As a peer guidance counselor, she’s a mentor for other students who are going through struggles similar to hers. Jones’ goal is to be the light in someone else’s life – something that she didn’t have growing up.

“I want to be the safe place for people that my friends have been for me,” says Jones. “We have so many different teenagers going through so many different things that having therapeutic support can mean the difference between graduating and dropping out for a lot of people … the difference between having hope and completely losing everything.”

. . .

Jones was born on October 29, 1998 to her mother and father who were both Quakers – a branch of Christianity. She was raised in a household centered around religion.

As a young child, Jones and her family attended church frequently. They also fostered a close friendship with the pastor of the church, and Jones and her brother spent a lot of time with him.

But when Jones was 5, her mother found out that the pastor they had known for so long was sexually molesting children. Her fear for her children overtook her, Jones recalls. She quickly became emotionally unstable, having multiple breakdowns in church and getting kicked out. She eventually was arrested.

“She would talk to angels, she saw Jesus on a slice of toast every day, she thought she had visions,” says Jones of her mother. “It became such a part of her everyday life that the supernatural side was calling her to fight a holy war that kept her from functioning like a normal person.”

Jones’ mother believed that she was meant to overturn the Catholic Church and bring justice to the issue, even though her faith in God stayed strong. The struggle became a strain on the family. In 2004, Jones’ mother decided to file for divorce. Jones was given a visitation schedule for both parents, but oftentimes conflict between them would prevent Jones and her brother from going to each house.

Jones was stuck devoting countless hours to her mother’s pursuit and had no way out. Her mother could not get a job and didn’t have any friends that she could go to because she had lost herself along the way due to her obsession.

Parents of Jones’ friends no longer wanted their children around Jones and her family. Jones was left to her own thoughts, feeling overwhelmed and confused. This quickly began a long chain of depression and anxiety for her.

At 11 years old, Jones stopped going to church. But this only made her relationship with her mother even more hectic.

“My mom and I used to have a lot of fights about it,” she says. “She very much wanted to keep me in church, but at some point … when I was coming into my own and developing my own opinions – I was pro-choice and queer – I realized that I wasn’t necessarily fitting in.”

Throughout all of this, starting when Jones turned 7 years old, her mother would physically abuse her.

At times when arguments between them became heated, her mother would push her to the floor, throw her down the stairs and even bite her. The abuse happened sporadically – sometimes once every few months, sometimes once every week.

As a former psychiatric nurse, her mother justified her behavior by telling Jones that Jones needed psychiatric care. Jones found it hard not to blame herself for the abuse because everywhere around her, she saw what she thought were perfect families and felt that she was a burden to her parents. In fear of being put into the foster care system, Jones stayed silent.

“There’s so much guilt,” says Jones. “When you try to think of your parent and recognize the fact that they’ve made some mistakes and did things that they should not have done, that were hurtful, that no parent should do to a child, you feel like you’re betraying them.”

It came to a point where Jones felt that she had only one way out.

“I was 11 the first time I attempted to commit suicide,” she says. “I would, every once in awhile, look back on the past few years of my life and think about how nothing had really improved and how all the bad things were still happening.”

She also points to the stories that her mother told her about the times that she had personally tried to kill herself as a child. The stories left an insurmountable impact on Jones, triggering her to think more about suicide.

Eventually, she couldn’t handle living with her mother anymore. So one summer night near the end of her seventh grade year, Jones snuck out of her second floor window, looking for safety at her friend’s house. She then transferred to her father’s.

“I felt frustrated, I didn’t want to be involved with it anymore,” says Jones. “I needed something to change … so I left, I just left.”

But after a month, she was forced to return to her mother’s house because of a court mandate. Coming back only made things worse for Jones. As an eighth grader, she tried to run away a second time, this time with the intent of dying.

After climbing up onto the kitchen counter, grabbing a fistful of sleeping pills and swallowing them all at once, she walked out the front door with no destination. “I wanted to stop living the way that I was living … trying desperately to leave it all behind, feeling like there’s no way I could possibly be free of everything that had ever happened,” says Jones. She survived and found safety at her father’s house once again.

Although staying with her father and stepmother wasn’t ideal for Jones, they still provided more emotional stability for her. She ended up living with them for the next four years.

But Jones still struggled with her mental health, and she suffered from frequent anxiety attacks. Her father and stepmother would often kick Jones out of the house in the middle of the night after listening to intense nights of hyperventilating and crying.

They tried to give her up for foster care. They would take her to hospitals and tell the doctors that she was suicidal, delusional and could not be trusted.

“It felt horrible to be in the situation of being rejected, but I understand why. I didn’t make it easy for them. I felt like I was getting in everyone’s way,” says Jones.

It became increasingly difficult to come to school throughout high school. She would often turn around on her way to school because of anxiety attacks.

During finals week of her junior year, Jones had a panic attack while trying to get ready for school. She struggled to breathe, couldn’t see straight and was hospitalized later that night. “It’s like being trapped in the most miserable state you could possibly think of, and your body just starts rebelling against you completely,” says Jones of the experience. “You lose sense of direction, you have no idea where you are. It’s horrible.”

She had reached a point where her body had completely shut down due to anxiety.

Her father and stepmother didn’t understand what she was experiencing. It became too much for them, and Jones felt that she would be safer at her mother’s. In the summer of 2016, Jones moved back in with her. She began attending summer classes to pass her junior year of high school. Throughout the summer, she saved up a stash of prescribed sleeping pills under her bed and one day swallowed a handful of them at once.

But shortly after, Jones called 911 and hospitalized herself, knowing that she needed help. She then waited at the hospital for her mother to come and support her, but her mother never showed up.

Jones was transferred to subacute care, where she temporarily lived in a group home among other teens. There, she realized that the comfort that she sought was not going to come from her parents.

Jones decided that from then on she would live on her own. With the goal of learning a trade at a Job Corps center, she prepared to drive to Seattle to stay with her grandfather. However, a monumental thunderstorm forecast for the day of her departure kept her from leaving. Instead she decided to stay the night at her close friend Alejandro Barbosa’s house until the storm passed.

Barbosa had always been there for Jones. “She had really been the constant for me,” says Barbosa. “We just have so many years of being close with each other.”

The next morning she decided to stay a few days longer. Barbosa made sure that Jones took her medication and constantly checked in about how she was feeling. “He became sort of a safe place,” says Jones. “He was a friend I could trust and bring my issues to.”

Linda and Cuco Barbosa, Alejandro Barbosa’s parents, enrolled Jones back into Grant as a Title X student in October of 2016 in order to finish her senior year of high school. They then made the decision to let her stay with them permanently. “My motivation was definitely to have her finish at Grant,” says Linda Barbosa. “I think what freaked me out was when I took Alejandro to visit her, (at the group home) and somebody said that she was going to be released in three days and basically had no plan and no destination, and that sounded pretty scary.”

Jones has lived with the family ever since.

“I didn’t think that I was gonna be able to graduate, I didn’t think that I was going to be able to get into college, I didn’t think that any of this would happen,” says Jones. “I don’t understand how people who are not my parents can be troubled with doing so much for me as Alejandro’s family has.”

Now, Jones uses her experiences to help other students know that they’re not alone.

Coming back to Grant, Jones joined the Reconnecting Youth class. It’s officially taught by the school social worker Kate Allen, but it’s often led by students themselves. “Sidney … comes with so much self-awareness and care for others that it was a natural fit to have her in the class,” says Allen. “Other people have seen that it’s okay to talk about hard days, and it’s okay to be upset and that everybody goes through hard things.”

After being invited back to the class for the second semester of her senior year as a peer leader, Jones stepped into the role that she feels she is obligated to do. “I know that I can really try to help students who know what it’s like to have a tough time, and I find that when I try to help people through different situations, I have a better handle on what I need myself,” she says.

Becoming aware of one’s surroundings, breathing and meditating are all examples of the mindfulness that Jones practices and teaches every week. To an extent, it’s unplugging from a constant stream of detrimental thoughts. For Jones, it’s a coping mechanism, a reset button.

On a recent Thursday as students begin to shuffle into room 19, Jones is putting her finishing touches on the mindfulness cards that she has created for Reconnecting Youth for the day. The students are all here for a reason: to be there for each other and support each other through the challenges that each of them face outside of school.

It’s 9:51 a.m. and the group sits in a circle. “You get out what you put in,” says Jones to the group. “If you feel that you can set out to be a part of this activity … I feel that we can get a lot out of this. Ready?”

Each person grabs a card, and the group proceeds to head outside to follow the instructions given to them. “A place that calms you,” “an interesting scent,” “a place that brings up strong emotions for you,” among others, are things that each student is to search for in the park.

The group circles up for a team breath, then disperses. One student finds peace in the sounds of the birds chirping. Another feels immediate nostalgia for her grandmother after looking up into the sky to find chemtrails like they had done together when she was younger. Jones lets out a deep breath and smiles, taking a step back to see that everyone has reconnected and grounded themselves.

As everyone gathers again, Jones leads a final team breath. “Y’all can keep your cards, and if you’re ever out and about and you find yourself getting distracted by things that aren’t so pleasant,” she says, “look around for your list and see if that can bring you back to your surroundings.”

For Jones, mentoring the group has given her confidence that she will be able to cope with her emotional instability in the future.

On her time outside of school, Jones also volunteers and works at Spark Arts Center, where she teaches young children how to create art.

Next year, Jones plans to attend Mills College to double major in childhood development and psychology, which will feed into a master’s degree in infant mental health. In the future, she aspires to continue to help children who struggle through many of the same things she has been through.

“Trauma rewires the brain, sometimes it feels like I’ll never truly escape,” says Jones. “If it’s at all possible that I can help alleviate some of the difficulty for another person so that they can reach the goals that they want to reach and feel safe … it’s just incredibly valuable. It changes you.” ◆