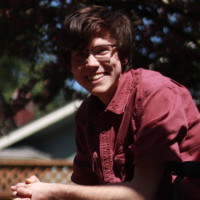

On the morning of Mar. 22, senior Stella Monteverde-Cakebread anxiously stood in front of the Grant student body packed into the crowded gym, waiting for the announcement of the 2019 Grant High School Rose Festival Princess. Before this year, she had never expected to stand on stage in front of an audience of her peers, let alone become the Rose Festival Princess.

Grant High School Rose Festival Princess. Before this year, she had never expected to stand on stage in front of an audience of her peers, let alone become the Rose Festival Princess.

But Monteverde-Cakebread has overcome her fear of public speaking. She stands tall, holding her head high in front of the audience at the coronation ceremony. Encouragement from her friends and family had helped her get to this moment, and she knew that they would continue to support her no matter the outcome. She was beyond surprised to hear her name called, crowning her as Grant’s 2019 Rose Festival Princess.

“I was very shocked. I was really close to crying,” says Monteverde-Cakebread. “I honestly didn’t know how to feel emotions … I was just really happy.”

However, her win did not come as a surprise to many Grant students.

“I think she is the kindest human being you’ll probably ever meet, and on top of that, really genuine,” says senior Mishya Mitchell, one of Monteverde-Cakebread’s friends. “She has a lot of energy. Even when she’s tired, she somehow exudes this positive energy.”

“I’m a pretty positive person when it comes to things. If a challenge comes up, I’m normally not one to back down right away. I’m just pretty positive all the time,” says Monteverde-Cakebread.

However, her life has not always allowed for this effortless positivity.

When Monteverde-Cakebread was 8-years-old, she began experiencing crippling headaches and discomfort throughout her body.

“For a few months, Stella had gone home early due to severe headaches and pains. Constant complaints of pains that would never go away. I thought it might have been growing pains, but as things got worse, we finally decided to get an X-ray,” says Dayna Cakebread, Monteverde-Cakebread’s mother.

As Monteverde-Cakebread’s health deteriorated, she began to realize that she was just not suffering from a regular sickness. Her affliction continued to worsen, eventually evolving into a fever. She remembers being in so much pain that she could not move her neck or arms. “As an 8-year-old, I didn’t know what was happening to my body, but I knew I was really sick, and that I needed to go to the hospital,” she says.

After visiting the hospital and undergoing multiple blood tests, Monteverde-Cakebread was diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). AML is a rare type of cancer — less than 1000 children are diagnosed in the US per year — that affects the blood, bone marrow and white blood cells of the individual.

“We went in on Feb. 2, 2010 to get a blood test. They sent us home, but we later received a phone call at eight p.m.,” Dayna Cakebread says. “We went to the hospital and received more testings to verify what she had. And that is when they told us, the doctors, that Stella had AML.”

The diagnosis came as a complete shock to Monteverde-Cakebread’s family. Her mother remembers feeling utterly lost.

According to The National Cancer Institute, the five-year overall survival rate for people with AML is only 27.4 percent. “It was devastating in the beginning, not knowing what the outcome was going to be,” says Dayna Cakebread.

“The cancer in my blood was deadly, so my parents never worried me with the percentage of my survival or that … I might not live,” says Monteverde-Cakebread. “They always kept me positive, and I had lots of friends and family who would visit me, and my room was very decorative.”

Luckily, Monteverde-Cakebread grew up in an encouraging home and always received full support from her family. They pushed her to try new things and strengthened her with their unfailingly positive attitudes. Throughout the ordeal, she remembers her family always being by her side.

“Family for me means everything. We are loud and loving. They have this energy with them that brings us all together,” Monteverde-Cakebread says. “They are always there for me.”

During Monteverde-Cakebread’s treatment, her parents dedicated their time to finding laughter and hope, creating a positive environment despite the unfortunate circumstances.

“She saw the smiles that she could bring when she had a positive outlook, and I think we just needed to lift others in order to have the strength to be hopeful that everything was going to be okay,” says Dayna Cakebread.

Friends from school would visit Monteverde-Cakebread in the hospital, helping decorate her room and playing games. It helped keep her connected to the outside world and made the hospital feel more like home.

The hospital was supported by foundations like the Children’s Healing Art Project (CHAP), which donated free costumes to patients, hosted bingo once a month and volunteered to keep patients company. Service animals and musicians also came to visit on occasion, spending time with patients individually.

Monteverde-Cakebread also remembers studying in a small classroom with other patients who were staying on her floor. Together, they learned math, reading and other necessary subjects that allowed them to keep up with their classmates outside the hospital. With lots of time to spare, Monteverde-Cakebread quickly became addicted to the “Magic Treehouse” novel series, which she read over and over again during her treatment.

“I was in the hospital long enough to where I was kind of adjusted to everything,” she says. “While some moments were scary, I had so much support that it wasn’t too scary to keep me in a trauma.”

The overwhelming positivity that surrounded her in the hospital helped Monteverde-Cakebread feel more comfortable and less afraid, even when she was isolated in her room. Patients like Monteverde-Cakebread are typically isolated when their immune system has weakened to the point that their bodies are unable to fight invading germs and bacteria. Because of the significant decrease in her white blood cell count, she remembers doctors coming into her hospital room dressed in full-bodysuits to examine her.

Monteverde-Cakebread was in and out of the hospital receiving radiation and chemotherapy for seven months. She underwent four doses of chemotherapy, each of which was five weeks long, and she remembers the treatment took a heavy toll on her body. She felt excruciating pain in her muscles and joints, and recalls nights where she could not fall asleep. She took medication to ease the pain, but as a third grader, she felt confused about what was happening to her.

For cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, one of the many side effects is hair loss. Growing up, Monteverde-Cakebread had long hair and recalls feeling reluctant to cut it short. But Dayna Cakebread, who is a hair stylist, encouraged her daughter to cut it because it would be easier to manage while her hair was falling out.

Monteverde-Cakebread was also allowed to dye her hair her favorite color, red. A photograph of her with her new red hair became the poster for Rock Star Stella, a fundraiser that Monteverde-Cakebread and her family started to help pay her medical bills.

“Rock Star Stella was an original fundraiser to help raise money to pay my hospital bills. It told my story,” she says. “And now it’s Rock Star Stella Gives Lights. We use my story now to raise money to buy nightlights and give them to my hospital floor for Christmas.”

Because the cancer was in Monteverde-Cakebread’s blood, a transfusion was necessary in addition to chemotherapy to replace the deficiencies within her bloodstream. However, because she is half-White and half-Latina, it was challenging to find a blood match, because only two percent of the population was eligible to donate. But after four months of waiting, she finally found a donor who matched her blood type. After the blood transfusion, her prognosis improved significantly.

“We felt relieved, and nervous not knowing if the match was going to work. But I knew I had to believe,” says Dayna Cakebread.

After seven long months in the hospital, Monteverde-Cakebread was finally cancer-free. “I had another chance at life. (AML) gave me a different perspective.”

But life was not entirely back to normal. During her treatment, she had developed a stress-relieving mechanism: She constantly rotated her wrists and ankles. Looking back, Monteverde-Cakebread remembers how her muscles tightened during the nighttime. She had to attend Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy for months, even after finishing cancer treatment. And because she missed so much school, she lost confidence in her learning abilities and needed tutors to help her catch up.

Although Monteverde-Cakebread was academically challenged in school after treatment, she had no trouble making new friends. She formed strong relationships throughout middle and high school and is known as an optimistic and loyal friend.

“She realizes that because she had cancer and there was a point where they did not know if she would live, she’s always been, even when we were young, she just tried to share that kindness and the opportunity she had with everyone else,” says Annalisa Caso, who has known Monteverde-Cakebread since sixth grade and continues to be one of her closest friends.

“Because there are people out there that didn’t have the same experience as her, and I guess she wants to be able to give them something in return,” says Caso.

“My freshman, sophomore year, watching all the girls up there representing Grant as Rose Princess, I was like, I am never going to stand up on that stage and represent Grant because I always thought only the popular girls do that. But after my junior year at St. Mary’s, I really opened up and I started pushing myself to try new things,” says Monteverde-Cakebread.

Monteverde-Cakebread transferred to St. Mary’s Academy for her junior year because of the move to Marshall campus. The culture at St. Mary’s challenged her academically, and she learned to try new things and be more involved with school activities.

“(St. Mary’s) showed me that there are things in life that we won’t connect with, (St. Mary’s) was one of them; I didn’t connect there like I did with Grant, but it was something new to try,” she says. “(St. Mary’s) helped me open up to taking in new opportunities, even if they don’t work out. You will still learn something from it.”

Monteverde-Cakebread decided to return to Grant her senior year because she felt a sense of belonging in the Grant community. After returning to Grant, both her mother and her friends pushed her to run for the Rose Festival Court.

“I had a few of my friends who worked for high schools (in Portland), and I was asking them what it was like to be a Rose Princess, and everything that I had heard was that it’s about giving back to their communities and not about (a) popularity contest on looks,” says Dayna Cakebread.

“Stella fits the description of being beautiful inside and out. She’s a great role model for all. I knew this would be an amazing experience to build her confidence and get more connected to a whole Portland instead of the cancer community.”

Monteverde-Cakebread was hesitant at first, but soon realized it was an opportunity to share her story.

After her application for Rose Princess was accepted, Monteverde-Cakebread went through the first round of the judging process. She presented a three-minute speech and was asked various personal questions by the judge. She recalls that it was a stressful experience, and memorizing the speech was difficult, but it helped her overcome her fear of public speaking.

After weeks of anticipation, the Rose Festival coronation finally took place at Grant.

Monteverde-Cakebread stood on the platform alongside the two other candidates, feeling a pit of nervousness in her stomach, but still beaming. When she heard her name called by Grant’s former Rose Princess, Melissa Torres-Duran. Monteverde-Cakebread was overwhelmed with joy and complete shock. She nearly broke into tears, not knowing how to react.

Her friends cheered from the crowd, unsurprised by Monteverde-Cakebread’s accomplishment.

“I am biased because I am her friend, but it’s a no-brainer that she did leave such a big impression, because she is just so genuine and honest and she is always so helpful and brave,” says Caso.

For Monteverde-Cakebread, representing Grant as Rose Princess was an especially rewarding achievement.

“Being able to come back to Grant my senior year made me feel whole again, being able to come back to a place I was familiar with and called home. I never thought I was going to be one of the girls to stand in front of the whole school and give a speech on why they should choose me … and then I did.” Monteverde-Cakebread says. “For Grant students to choose me, I was overcome with joy and happiness. I was no longer that corner kid. I became the Rose Princess of a school I loved.”

“I still get teary-eyed when I share the video of her winning,” says Dayna Cakebread.

“Witnessing her stepping into her light as a young woman makes that moment so much more powerful, that she gets to live her best life and enjoy life’s gifts. This a huge turning moment. I am so proud that she is embracing every moment.”

Monteverde-Cakebread’s last day of school was on May 1. She is now focusing on her responsibilities as Grant’s princess, along with the 14 other Rose Festival Princesses across the Portland metropolitan area.

The Rose Princesses will spend five weeks gathering at hospitals to meet patients, visiting senior centers to meet the elderly and touring the Portland International Airport.

“Rose Princess has given me an opportunity to give back to my community but also get to see Portland in a different way,” says Monteverde-Cakebread. “With all the traveling, I’m constantly learning about new things. So far, being on the court has taught me that I am capable of doing things, like speaking in public,” she says. “It was one of my biggest fears, but now I am able to do it more calmly.”

This fall, Monteverde-Cakebread will be attending Linfield College in McMinnville, Ore. Her goal is to pursue a bachelor’s degree in nursing. Her interest in the field piqued during her treatment because of the nurses who supported Monteverde-Cakebread and inspired her with their eagerness to help.

“When I was in the hospital, I got to see the nurses and see what they did on their daily jobs and the way they interacted with people and the machinery, and watch them go about their day,” she says. “It seems like a lot of work but becoming a nurse is definitely a way for me to give back to what was given to me when I was a kid, and it’s in a form that I feel like I can do.”

Monteverde-Cakebread continues to work with CHAP and other charities and hopes to encourage positivity — even when life takes unexpected turns.

“With all the love and support that was given to me, it kept me positive, surviving cancer kept me positive. It makes me want to give back and help others like I was helped, to spread joy and love to others.”