On Oct. 9, 2018, a draft of an intergovernmental agreement between the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) and Portland Public Schools (PPS) was presented to PPS’s Board of Education. The intergovernmental agreement proposed that the district pay over $1 million per year of personal funding to maintain school resource officer (SRO) presence in schools, instead of the city, who have provided funding for SROs for over a decade.

According to the National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO), an SRO is a “career law enforcement officer with sworn authority who is deployed by an employing police department or agency in a community-oriented policing assignment to work in collaboration with one or more schools.” Since Columbine High School’s 1999 massacre, police presence has steadily risen in schools across the United States. NASRO states that, as of 2018, about 30 percent of American schools employ at least one SRO, up from 10 percent two years before the Columbine shooting.

Following the proposal, many students and families raised concerns surrounding this use of funding, claiming it could be better used in other ways. “We could be using that funding for so many other things,” says Lincoln High School student Mayah Garcia-Harper. “I have holes in my ceiling at Lincoln from tiles falling down.”

Additionally, community members came together over concerns of the disproportionate effects of SROs on students of color, worrying that they are subject to the same racial biases as regular police officers. “Captain Hager, the person who kind of oversees the SRO program, seemed pretty adamant about denying that SROs contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline in Portland. And the SROs kind of echoed that sentiment as well, that ‘Portland’s different, we don’t contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline,’” says Grant parent, Aoi Mizushima.

Grant’s data in PPS’s yearly Discipline Referral Report shows disproportionate punishment of students of color versus white students in terms of expulsions and out-of-school suspensions — in the 2017–18 school year, 5.8 percent of Black students and 4.8 percent of mixed students were expelled or suspended, while only 1.2 percent of White students received similar disciplinary action. As of the 2018 report, Grant was 72.2 percent White.

SROs are specially trained to prevent biases such as these, but some believe racial bias is inevitable when it comes to police interaction. “I’ve had experiences when I was younger … walking around the store and not being allowed to touch certain things while my White cousin was able to play with all the toys he wanted,” says Garcia-Harper. “So I know how it feels, and it’s not a good feeling and I would hate for people to go to school where they’re supposed to feel safe, secure and have that pent up anxiety, like, ‘Am I going to potentially be in a conflict (with police) today?’”

Following the initial Board of Education vote, Garcia-Harper joined the activist group “NoSROsPDX,” which criticizes SRO presence through social media and student interaction.

However, not everyone has concerns surrounding armed officers in schools. Board of Education member, Paul Anthony, is an enthusiastic proponent for SROs. “People want to think that it’s an armed person who is there to stop someone who’s coming in to shoot up the school … (SROs) are not there for that. They are certainly not there for enforcing student discipline at all,” he says. “Our school resource officers are there to address threats to our students that are happening outside of school. Students who are being abused, students who are being molested, students who are having a hard time accessing the social services, the physical services that they need.”

The debate around the benefits and risks of SROs in schools is a highly contentious and multifaceted issue, due in part to the lack of information surrounding their place in schools. A 2009 issue of the Journal of Criminal Justice says that research around this topic is limited and often based on speculation, leading to confusion around whether or not having police in schools is actually effective.

“When I got on the Board, the district had its own police force,” says Board member Julia Brim-Edwards. “We went through a major recession, and at the time PPS was one of the few school districts in the state that was actually paying for law enforcement services.”

Over a decade ago, because of a shrinking budget due in part to the nationwide recession, the district could no longer afford to fund their own police services. The City of Portland began to provide officers to schools at no cost to PPS. When PPS’s superintendent took office, he and the police chief felt the need to formalize the rules of engagement between PPS and PPB.

Prior to the Board vote to implement full-time SROs funded by PPS, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Oregon asked the district to either delay or cancel the vote altogether.

In a letter addressed to the Board, ACLU Oregon reported that members of the PPS community had reached out, concerned over the Board moving the intergovernmental agreement through without adequate opportunities for public comment. ACLU Oregon reminded the Board that their Staff Analysis and Report showed that input was not sought out until late in the process and was with a limited number of student representatives.

However, the Board continued with their planned vote at the Dec. 11, 2018 meeting. Though five student engagement sessions had been scheduled for the week leading up to the vote, many students still felt that they arrived at the Board meeting feeling excluded from the decision-making process.

Claiming that the decision to implement SROs was rushed, Board member Scott Bailey proposed pushing back the vote until 2019 to allow for more community input. However, this idea was rejected by the Board and Bailey made the decision to vote “yes” at the Dec. 11 meeting. “Who do we want responding (to 911 calls at schools)? Do we want a regular police officer, or do we want someone who really likes kids, and that’s why they got into being a school resource officer?” says Bailey.

Board member Amy Kohnstamm abstained from the vote, citing the lack of input from students. “You know, I think (student input) is critical for everything the board is called on to decide. But this is an issue that, you know, directly impacts students everyday, an area where … students should have been right front and center in the conversation.”

But not all of the Board members were able to meet with students before voting on the intergovernmental agreement. Dr. Julie Esparza Brown, the only Board member to vote against the resolution and the only person of color on the Board, was out of town in the time leading up to the vote; however, she says she would welcome the opportunity to sit down with students.

“My responsibility is to keep everybody safe,” she says. “I had a voice in developing the resolution and putting some protective measures in there, like really looking at the data segregated by race. What did the trends looks like? (But) ultimately in good conscious I couldn’t vote for it knowing what our students of color were feeling. It was a really tough one; it’s still a tough topic. I’m not sure what the answer’s going to be to it.”

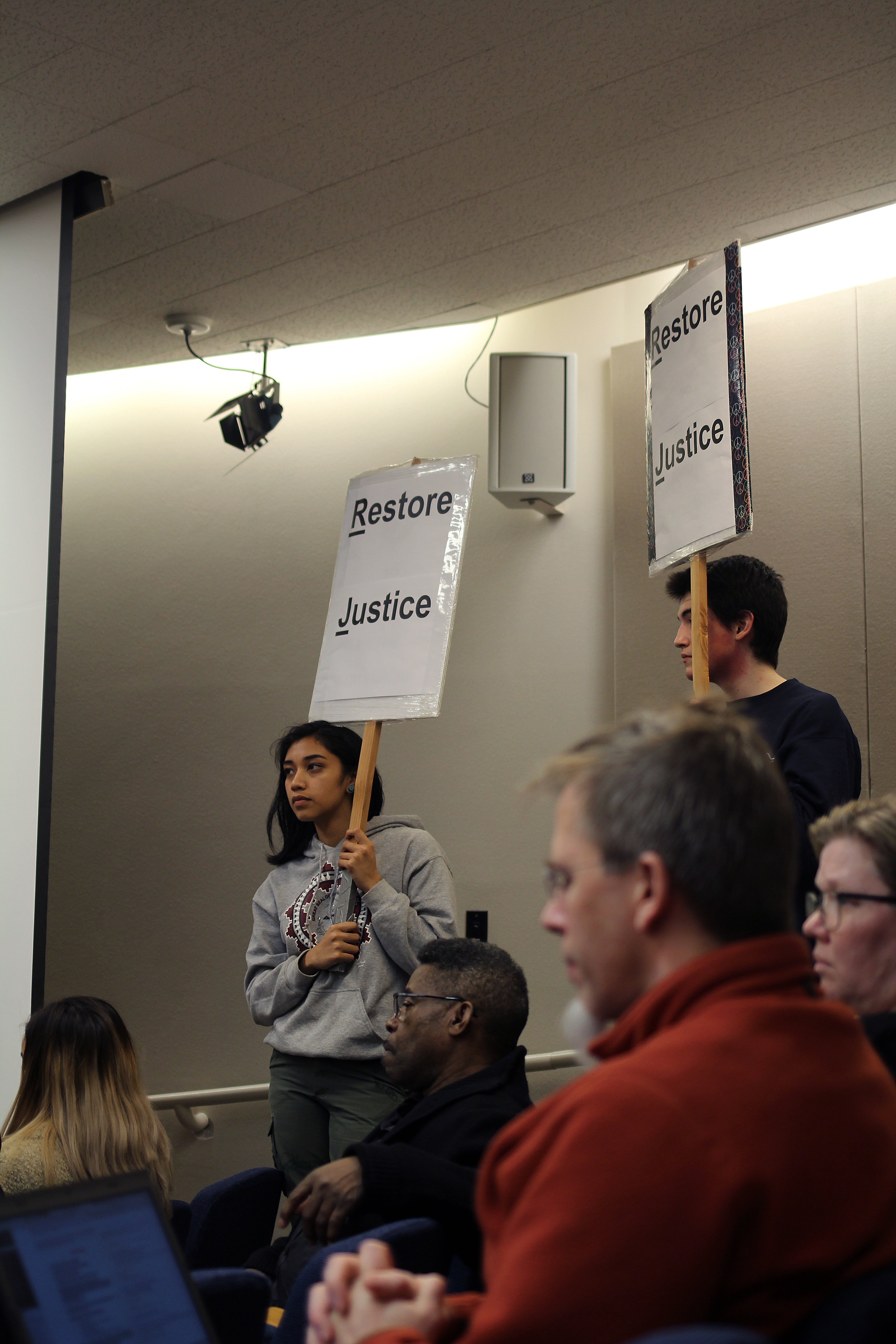

The intergovernmental agreement passed by a 4–1 vote on Dec. 11, resulting in prompt backlash and action from PPS’s anti-SRO communities.

On Jan. 2, students across the district held a press conference to protest the decision to implement full-time SROs in PPS. Eleven students, some with their family members or other adults, gathered on the steps of City Hall holding signs that read, “COPS OUT OF SCHOOLS.”

“(The conference) was a really interesting experience. I think that it demonstrated how the conversion around this issue has not really been made accessible for students,” says Jefferson High School student, Max Nathe. “There was a very limited turnout, which I think is entirely reasonable considering that it … was a Monday morning. I was only able to attend because I didn’t have a class first period that day. I think it demonstrates lack of awareness, but it also demonstrates the willingness that does exist among students to actually get out and say stuff and … make their voices heard.”

Student organizers across the district met with members of Don’t Shoot Portland — an accountability group formed by supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement — to examine the actions of PPB. The two organizations met to discuss next steps, and how to create a more efficient movement.

On Jan. 14, a meeting was held between the Board of Education Chair, Rita Moore, PPS’ Superintendent Guadalupe Guerrero and Mayor Ted Wheeler. Following the meeting, Moore made it clear that the intergovernmental agreement would not have the Board of Education’s approval and needed substantial revision. PPS was no longer willing to use their limited funding to pay for SROs, believing that public safety is essentially a city responsibility.

After meeting twice with Mayor Wheeler herself, Brim-Edwards introduced a resolution to suspend the ratification of the intergovernmental agreement. For Brim-Edwards, the tipping point was the amount of money the school district would be paying.

“The police bureau is saying, ‘We have these tactics which we think are much more appropriate for working with our students … and yet if we’re going to provide that better service in the school environments, you’re going to have to pay extra,’” said Kohnstamm at the Jan. 29 meeting of the board.

After Brim-Edwards met with Wheeler,, she says it became clear that the deadline the board was given was earlier than necessary, as the decision was not as time-sensitive as had originally been expressed.

Dr. Esparza Brown expressed the Board’s concerns surrounding the deadline and addressed the concerns brought by the community at the Jan. 29 board meeting. “We understand that the SRO issue is a critically important concern for students and the community and in particular students of color. And the board shares an interest in finding ways to preserve safety without sacrificing students’ civil rights or sense of comfort in community and their schools,” she said.

Later in the meeting, several students from various PPS high schools filled speaking slots, expressing concern for the way the intergovernmental agreement had been handled by the Board in terms of timing and lack of community engagement about the issue.

One student’s testimony stood apart from the others. Grant junior and SRO advocate Ben Snead was critical about the Board’s decision change. “I don’t understand how, just because there’s some controversy around it, we’re on the cusp of totally changing our position on this. That doesn’t make very much sense to me,” Snead said to the Board. “And I would hope that public officials would be stronger in their convictions about what needs to happen.”

The board expects to have revisions to the intergovernmental agreement in late February, but a specific timeline is unclear. “I think it’s a black mark on our board that we did not delay at that time (of the original Dec. 11 vote),” Kohnstamm said at the Jan. 29 board meeting. “There shouldn’t be a time when expediency trumps student voice in our decision making.”

Julie Esparza-Brown

Vice Chair of PPS’s Board of Education

She/Her

“As a person of color I have experienced at times, you know, challenges with police, particularly when I was younger, that caused me to actually have some anxiety around police. And that’s not uncommon for people in communities of color. So it’s a difficult position in that my role as a board member is to ensure the safety of all students. That’s one of my big responsibilities and that’s not one that I take lightly. So understanding now, with the increase of gun violence across the nation, particularly in schools, I mean it’s a tough question to have to address … I understand that for marginalized communities police presence — and particularly armed presence — then feels threatening. And you know, one of the reasons I became an educator over 35 years ago and on the school board is to change the educational opportunities for marginalized communities … For kids of color having those police or the SROs on their campus may put a barrier (to education) there that I’m trying to break down … Statistics show in too many cases there’s an overreach by the justice system, by SROs, by the police system, to kids that need other kinds of interventions other than punishment. That’s a huge concern for me.”

Mayah Garcia-Harper

Junior at Lincoln High School

She/Her

“I think we’re misusing our funding. We already have security guards and, to me, adding guns just fuels the fire … We already have enough going on, we all know that guns are dangerous, so why are we adding more? Especially giving (guns) to a person that has a lot of authority … that’d be very intimidating, very scary. I know for me, anxiety-provoking. One of the things that the board members were saying … (was that SROs) are going to be your counselors, they will be there for you, talk to you, do whatever you need, but that’s not really what’s happening. They’re very intimidating. They stand in the corner, they’re wearing bulletproof vests, they have a gun strapped to them. I wouldn’t go up (to them).”

Ben Snead

Junior at Grant High School

He/Him

“I think the idea of having school resource officers in schools is a good one, I think it would help foster a better relationship between police officers and students and the community in general … I think we all, as a city, every citizen in Portland needs to be able to rely on the police whether or not they interact with them on a daily basis. We all need to live in a city where each one of us — regardless of our identity — can be able to trust the police, and if we build relationships with the community with specially trained officers at a young age then I think that can make those relationships a lot better in the long run … Saying that there are issues with policing and school resource officers with some anecdotal cases across the country, I don’t think is a fair argument … It’s interesting to say that students of color feel uncomfortable around police officers … I think that it’s very important to focus, again, if there’s statistics to show that when we have Portland school resource officers in schools they disproportionately have some sort of reaction to students of color, then I’d be really interested in seeing those numbers, if they exist.”

Aoi Mizushima

Grant Parent

She/Her

“I think that (racial) bias exists and the studies across the whole country show that there is a disproportionate targeting of marginalized groups. I feel like it’s just really dangerous, actually, for Portland to think that we’re somehow immune, that our police officers are somehow immune to that (bias). The data shows otherwise … I think that allocation of resources is a major issue especially, I know all the basic things that schools are lacking in, some very basic materials and supplies and textbooks and the list goes on and on. And then I know that there was money taken away from restorative justice, I think that might have happened last year … I just feel like if there is going to be a use of this amount of money, there should really be solid data to back up … the goals and trying to define what their goals are, just because safety is very subjective. When you ask what creates a safe learning environment, it’s tricky because people have different views on that.”