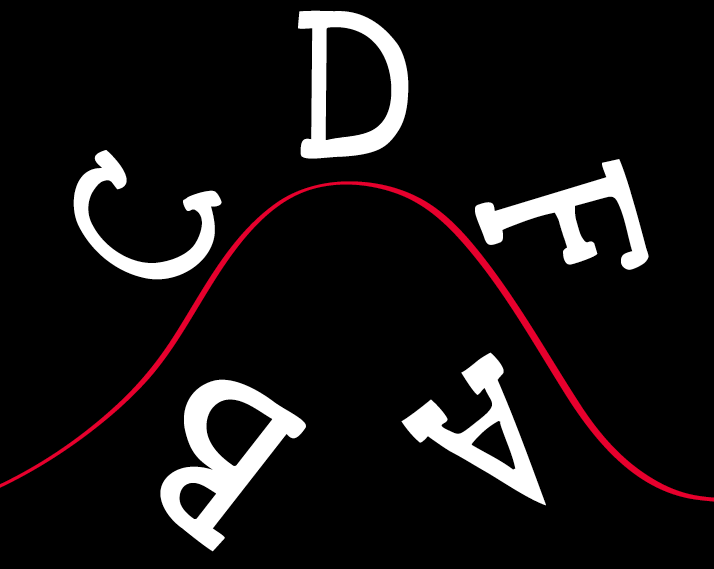

The author questions motivations for educational success as students face pressure to fulfill the concrete standards of a system designed to build boxes.

“Ring-ing!” Students flood out of Grant’s classrooms and walk to their last period of the day. I walk down the bustling main staircase and head to my classroom in the basement. As I enter, a rush of cold air hits me, invoking a whole-body response. I sit down at my desk, overwhelmed, and look up at the whiteboard ahead.

In black crisp Expo marker, it reads “Test day, no notes.” I groan. In this class, tests are weighted as 60% of our grade. This also happens to be my worst subject. I failed the last test and even with a slight improvement after my single allowed retake, my grade hangs by a thin thread, wavering between two letters.

My GPA hinges on this moment. The exam commences and I look over the questions carefully, answering them each to the best of my ability. I press submit, somewhat confidently, but unfortunately, the results disappoint. I stay after class to retake the test. Still unhappy with my score, I decide to give it another attempt. Everyone has left at this point. I am alone and confused. I try again and finally get full points.

Even after improving my score after multiple failed attempts, something doesn’t sit right with me. It doesn’t feel like I have learned anything. It doesn’t feel like I have made any true progress. It feels like forced repetition, with nothing but trial and error until I am finally deemed acceptable. The relief I feel this grade brings me has nothing to do with a sense of accomplishment, but rather the feeling of being set free after so much drilling and memorization.

After reflecting on the emotions I felt, I thought back to conversations in classes where the majority of students share similar thoughts about the pressures they face every day in school and the anxiety and discomfort they feel when being assigned grades or taking tests. I came to an understanding: motivations for doing well in school are flawed.

The flaws are systemic, rooted in teachers having to assign numbers to students in order to test intelligence, and final performance as opposed to attributes of effort, creativity, or emotional intelligence. This process overall puts great emphasis on the relationship a number assignment has to our worthiness as well as our understanding of personal aptitude and intellect.

More choice material needs to be introduced to students so that they can find and utilize methods that fit best for their learning. I believe that more hands-on projects and fewer standardized tests would also greatly benefit students and move them a step closer to rejecting harmful standards, boxes and rankings.

I feel that a lot of students can relate to feeling non-constructive pressure directly linked to grades with intentions that lie not in succeeding or doing well, but rather in meeting a set expectation. I experience unhealthy associations and ties to self-worth based on grade performance which leads to an extreme drag on my mental health.

Therefore, so much of my work is a reflection of how I value myself, so when I do poorly, my image and self-worth suffer. My earlier years of education encouraged creativity, curiosity and self-expression which resulted in increased engagement and learning. In high schools, the primary focus is on restrictive ways of measuring intelligence in a mission to prepare students for the workforce which leads to less engagement and input from students.

Author and Harvard professor of neuroscience, Todd Rose, states, “In higher ed we have a brutally standardized system. It doesn’t matter what your interests are, what job you want, everyone takes the same courses in roughly the same time and at the end of the course you get ranked.”

I would like to acknowledge that most teachers are not at fault. The system overworks teachers and doesn’t provide reasonable pay, resources and recognition. These things are further exacerbated by current staffing issues related to the pandemic.

Teachers teach state requirements for curriculum. These requirements are not set up for individual freedom and growth. In the article Bored Out of Their Minds, Zachary Jason says, “By designing for the average of everyone, the classroom is ideal to no one. And in this design, boredom runs rampant, and there’s no room for a cure.”

When students are disinterested or frustrated by either their performance or the way they are being taught, they disengage, which causes them to fall behind as work begins to pile up. A Grant freshman talks about their experience in physics class saying “I haven’t done well in physics for a while and I’ve lost so much motivation knowing it’s just not something I understand. I fall behind further and further till there is no point in even trying to make it happen which disappoints my family and myself.”

This is a common struggle. When I get to a certain low point, it is often difficult, if not impossible, to pick myself back up. A Grant sophomore touches on the root of this discouragement, “We are taught from such a young age that good grades equate to intelligence. This is completely false … school is designed for teaching hundreds of students the same lessons in the same exact way.”

In the past couple of years, Gallup has conducted over 5 million surveys for students in grades 5-12. Their findings have been stark . In an article on their website, they write, “Almost half of students who responded…are engaged with school (47%), with approximately one-fourth ‘not engaged’ (29%) and the remainder ‘actively disengaged’ (24%).”

A pattern in engagement by grade level also reveals itself in these reports. “Engagement is strong at the end of elementary school, with nearly three-quarters of fifth-graders (74%) reporting high levels of engagement. But similar surveys have shown a gradual and steady decline in engagement from fifth grade through about 10th grade.”

Some people may argue that grades are, in fact, good motivators and significant confidence boosters. The opposite is true. A 2019 study found that intense academic pressure is directly associated with mental health struggles, with symptoms such as anxiety, depression, increased substance use, burnout, and depersonalization.

I feel a constant weight knowing how my well-being so heavily depends on my academic performance and the sacrifices I make to succeed and fit these set expectations. This has much to do with the amount of pressure that kids are put under by schools to do their best in an atmosphere that is extremely unrealistic for the majority to achieve.

The system is completely based on a linear understanding of the “average” student. The reality is that there is no average student. We are all unique and learn differently and the way we are taught needs to be changed so that we are able to reflect these requirements for every individual. There needs to be more freedom in the setting of education in order for progress to be made.

In the end, much attention needs to be brought to this issue so that reworking can commence and more specificity for each learner can be forged, enhancing our ability to stay engaged, keep on top of our work, and keep us forever growing.