“Down and Out in New York City” by James Brown floats through the room and bottles clink in the minibar as Malcolm prepares a drink to toast to an evening of success.

He yells to Marie from across the house, “You look good tonight, baby.”

“What?”

“I said you look beautiful tonight!”

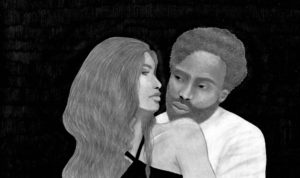

Malcolm, played by John David Washington, dances from room to room in celebration, sweeping through the stunning house in bliss. As he arrives in the kitchen, Marie, played by Zendaya, joins him to hastily make a pre-bedtime meal of boxed mac and cheese. As Marie prepares their food, the facade of exhaustion on her face melts into resentment as Malcolm begins to reminisce on the evening.

“Malcolm & Marie” is the story of a long night of soul-searching conflict between a young couple, Marie and Malcolm, after they return home from Malcolm’s movie premiere. This 1hr 45m conversation dissects the pair’s dysfunctional relationship, Marie’s role in the creation of Malcolm’s film and how Black art is critiqued in Hollywood.

“So much is told, not shown.”

Off the bat, it is apparent how the two person cast and singular setting shrink the possibilities for storytelling techniques. Most of the plot is conveyed solely through dialogue. At times, the main characters seem flat and underdeveloped due to the limited perspectives and context. Any essential background information is forced into the script awkwardly. It lacks fluidity and makes the dialogue even more unrealistic. So much is told, not shown.

The majority of the film’s run time is spent on dialogue between the couple, which tires quickly. Malcolm and Marie exchange vehement mini-monologues with each other without climax as one of them walks off or a half-hearted, passive-aggressive solution is reached. The breaks between the arguments are short-lived, though; it isn’t long before a new comment arises to set them off, and the cycle continues. While fights do wax and wane in real relationships, the choice to make them argue in real time in a singular setting makes it all feel maladroit and claustrophobic. It reads like a cheesy one-act play that drags too long.

The cinematography is a major highlight of the movie. Paired with the minimalist set and lighting choices, the black-and-white color scheme beautifully emphasizes shadow and depth in each scene. The main shooting location of the film is the Caterpillar House, an open, modern, ranch style house located alongside a picturesque desert background in Carmel, CA. In addition to the location and cinematography, the acting stands as a strength of “Malcolm & Marie.” Zendaya and John David Washington deliver career-defining performances, both giving unparalleled energy and passion throughout the entire film. Their on-screen chemistry is phenomenal, bringing life to the otherwise tedious script.

Director Sam Levinson’s voice is strongly present in the film through his characters, especially during Malcom’s rants.

Malcolm goes on a variety of rants throughout the film, but the most memorable and controversial of them is about critics. Throughout the film, Malcolm frequently references (and ridicules) a complimentary yet superficial review written by a “white lady from the LA Times” years prior about his previous works. Malcolm elaborates on the tendency of reviewers (like this one) to project politics into their interpretations of Black films, rather than acknowledge a Black filmmaker’s merits in the art of directing and writing.

While the critiquing of Black art is a relevant issue within Hollywood that needs to be examined, the question arises as to whether Levinson is the right person to lead the conversation. As a white person in Hollywood, is it his place to write a Black character who’s speaking on this experience?

This is especially true when a lot of his points look much more like personal grievances than genuine introspection into the system. With research, it becomes more apparent that this heavily-mocked “white lady from the LA times” character seems a lot like real-life LA Times critic Katie Walsh, who left an unfavorable review of Levinson’s 2018 film Assasination Nation. He covertly belittles Walsh and reviewers in general through Malcolm’s rants, declaring their inability to understand nuances of character and other aspects of filmmaking.

The film presses forward through this contentious rant, and the fights between Malcom and Marie continue to swell and dissolve. As time passes, it becomes increasingly clear that a 20-minute short film would have been more viable to tell this love story than a full-length feature, given the flimsy structural development.

The couple finally decides to go to bed after Marie goes through a moment of emotional catharsis that leaves both with a lot to consider. They leave their fight unresolved and the fate of their relationship undecided.

“I’m sorry,” Malcolm whispers from his side of the bed.

Marie clicks the lamp off and hesitates to reply.

“Thank you.”