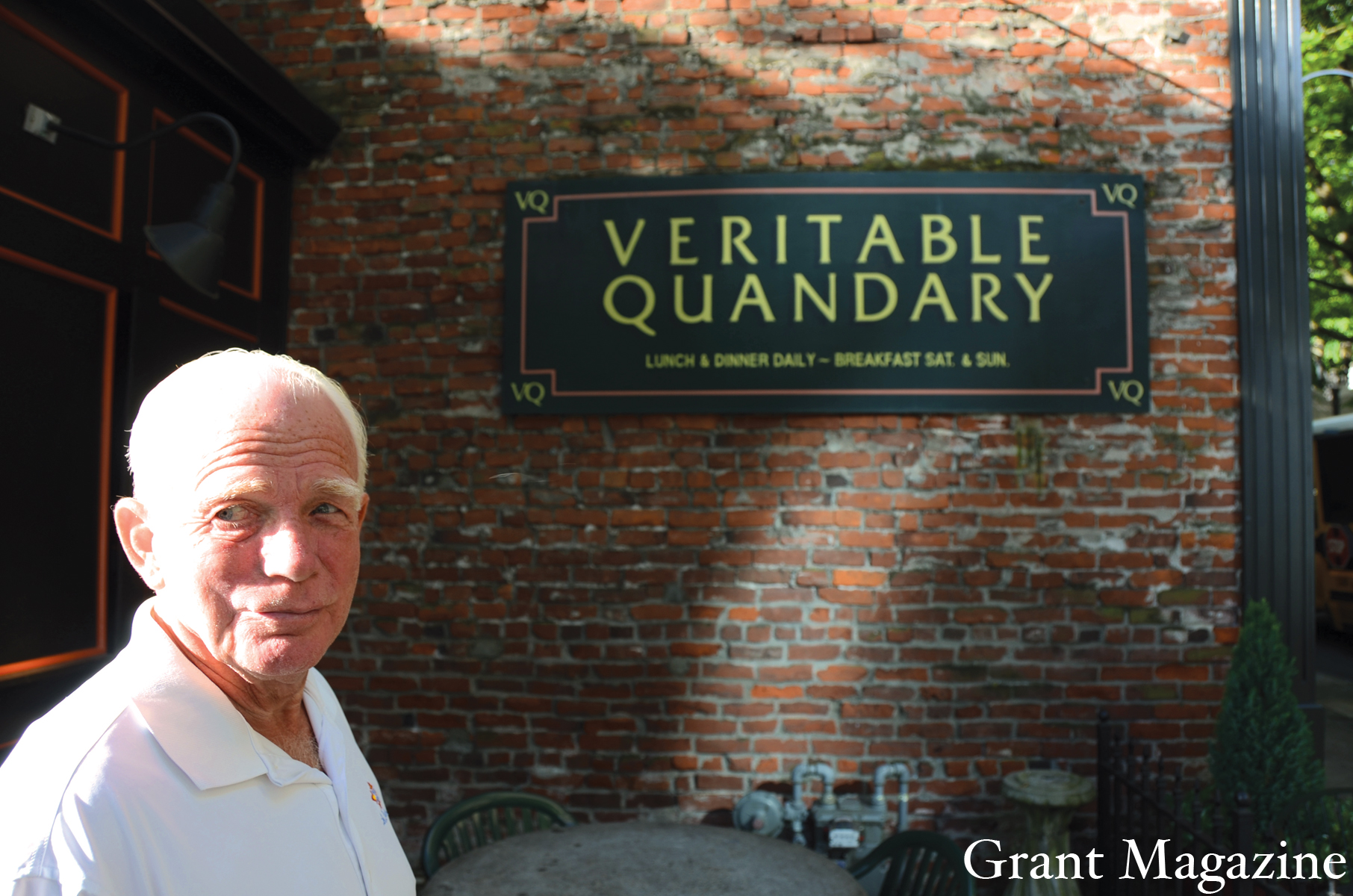

It’s just after 6 a.m. and Denny King is in the garden of his restaurant, the Veritable Quandary. He takes a worn garden hose and waters the plants, taking time to examine some roses as he goes along. Next, in his cluttered office, King goes over the books for the previous night. Staff members come by and he pauses to chat.

By 11 a.m., the staff has taken over. King sits down at the bar and orders some food, watching customers enjoy their meals. The energy of lunchtime picks up rapidly and the day moves forward.

King, 71, is a member of Grant High School’s Class of 1961. He has spent the majority of his life managing the establishment known around Portland as the VQ. Since it opened in 1971 as a small “college tavern,” the VQ has evolved into an upscale dining institution. And it’s all due to King’s strong work ethic.

At times, King says, the VQ “was all I had to my name. I was on the verge of bankruptcy so many times, but I just fought to keep going.”

Even now, King still works at the VQ every day, but he’s beginning to slow down. After several decades of work, he finally has time to enjoy the fruits of his labor.

Even now, King still works at the VQ every day, but he’s beginning to slow down. After several decades of work, he finally has time to enjoy the fruits of his labor.

King was born as the younger of two children on Jan. 19, 1943. He grew up on Northeast 24th Avenue and Clackamas Street in what’s now the Sullivan’s Gulch neighborhood. His family lived in an old, beautiful house – one of the nicest in the neighborhood, he says – that King’s father, Donald King, bought for a bargain price of $6,500.

“It was all brick and it had ivy on it, and was surrounded by azaleas and roses,” King recalls. “It looked very much like it should be sitting in the country by itself.”

At an early age, King was diagnosed with rheumatic fever, a now treatable condition that plagued him with heart problems. It kept him at home for much of his childhood. There were years when King attended school as few as 80 days. He would spend time listening to the radio or doodling on a notepad, if he wasn’t busy fighting off a fever.

“It affected me a lot in my inability to interact socially,” says King, who was introverted most of his childhood and even up to college. But he remembers his peers often wrote him letters full of school updates and messages saying “Miss you” and “Get better soon.” In the third grade when he was especially sick, some friends helped him with his assignments so he could move on to fourth grade the next year.

Aside from being ill, King led a traditional post-war, baby-boomer American life. He would pass his time drinking milkshakes at Robertson’s, the local pharmacy, or getting burgers across the street at Riddle’s Café. He and his friends would collect baseball cards and analyze baseball statistics from King’s favorite team, the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Baseball was one of King’s favorite pastimes. At age 9, when King began to outgrow his fever, the first thing he did was sign up for Little League. “I played centerfield and made the All Star team my first year,” he remembers. “I was so proud.”

King’s home life wasn’t a breeze. His father worked as an accountant and his mother worked at an insurance agency. Even with both parents working full time, there was little income. “We didn’t have any extra money,” King recalls. “On Saturday night, the four of us would scrape together 45 or 50 cents and get a quart of ice cream and watch TV.”

To help with his family’s financial situation, King got his first job at 9. “In my family, everybody had to earn their own money,” says King, who delivered newspapers after school, making as much as $30 a month. It was challenging, but King got used to it. “You didn’t know that it was hard. It was just something that you would have to do,” he says.

King’s family didn’t go on many vacations, but he recalls one vividly. When he was 13, his family drove from Portland to Michigan, where King’s father was from. They stopped in Chicago and heard the Dodgers were playing a double header at Wrigley Field. With money saved from delivering newspapers, King bought himself and his father tickets to the game.

He remembers walking into the ballpark. “I had all my heroes in mind: Don Newcombe, Gil Hodges, Duke Snyder, Jackie Robinson,” he remembers. He had all their baseball cards, but seeing them live was different.

A year later, King was out of middle school and off to Grant. Though he remained shy throughout high school, he had a great experience.

At the time, Grant had a lofty reputation. It was one of the top schools in the country academically, and it was a big name in the Portland social scene. “If you were from Grant, you were something,” King recalls.

It was at Grant where King became interested in issues around social inequality. While he loved Grant, he noticed bigotry throughout the school. King remembers protesting the school’s fraternity. The fraternity had a clubroom in the cafeteria, but only members could enter, a rule King despised. “I thought, ‘No, I am not going to go in there, leave everybody else and act like a big shot,’” he says now.

“In my family, everybody had to earn their own money. You didn’t know that it was hard. It was just something that you would have to do.” – Denny King

Racial biases were not uncommon, especially regarding the small number of African-American students. During one assembly, King remembers an African-American student being barred from performing. “This little sophomore kid was going to come out and sing a Lou Anthony song,” says King. “The principal went out on the stage and said ‘You can’t sing it,’ because it was ‘black music’ – rock and roll.”

The student body booed the principal off the stage. “I was appalled that there was some sort of prejudice going on,” King recalls.

One conflict that really opened King’s eyes to the racial clashing happened in 1958 at a Grant basketball game. During the game, three African-American kids were harassing King. “They didn’t have anything against me personally,” says King, “but I was the one who was there, and they kept pushing me in the back, pushing me in the back, pushing me in the back for four quarters of the basketball game, and I wouldn’t move.”

After the game, the trio was waiting for King outside the gym. A crowd of students formed around them, expecting a fight. “One guy slugged me,” King recalls, “and I said, ‘If that makes you feel better, then go ahead and do it. But I am not going to hit you back.’”

The other kids were at a loss and the tension quickly evaporated. Although there was no fight, for King it was a victory. “It was of great significance to me,” says King. “I knew I wasn’t going to fight, and I knew we could be friends. That whole interaction just exploded in my mind as an awakening to the Civil Rights period.”

In 1961, King graduated from Grant and enrolled at Portland State University. There he studied political science and philosophy. A year later, King married his high school sweetheart, Jane Lodmell. By the time he was 21, they had two kids.

To support his family and pay his way through college, King worked in a warehouse, where he unloaded cargo coming in on trains. He hated it. It was “very, very hard work,” he recalls. “Filling out water heaters and carrying them on your shoulder 50 yards – those things were heavy. I got in great shape.”

The social bigotry King had seen at Grant was also present at work. “I learned that there was a side of the cafeteria that whites sat in and a side that blacks sat in,” says King. “So I sat on the black side.”

After a couple of years, King’s marriage began to suffer as the couple drifted apart. “We went different directions,” King remembers. “She was racing through school, and I grew my hair long and was kind of a protester.”

In 1966, their marriage ended with a messy divorce. Because King was too poor to afford lawyers, Lodmell received full custody of the kids, leaving King completely alone. “I never got to see those two kids,” says King. “She took them and ran away with them and that broke my heart.”

After the divorce, King slipped into a brief period of depression. He began to drink more and stayed out late. One day he woke up, showed up to work at the warehouse and told the boss he quit. “I had lost my family and I hated doing that kind of work,” he says. “I said, ‘I can’t do it anymore.’”

For one week, he was unemployed. He remembers it being the longest week of his life. “I had never not worked,” King recalls. “It was actually kind of scary.”

He got a job as a janitor at PSU, working the graveyard shift. At the same time, his interest in social movements intensified and it helped break him out of his shell.

“I was on my own,” King remembers. “I wasn’t going home every night to a wife and two kids. I was out with guys with PhD’s, philosophy professors talking about issues: the world and bigotry and racism.”

King started attending small demonstrations, including a failed attempt to occupy the newsroom at PSU’s campus newspaper. The most prominent demonstration King remembers was a march down Broadway to protest the Vietnam War. He marched along with 10,000 other protesters from the PSU campus to the waterfront. “Every office building was throwing their garbage on us out the window,” recalls King.

It was King’s interest in the social movements that inspired him to open the VQ. For a while, he and his friends would hang out at the Chocolate Moose, a bar King managed. By the time he graduated college, he wanted to run his own place.

So he decided to get a space and named it Veritable Quandary. He got the name from a book he was reading at the time, feeling a connection to the phrase. “That’s where I was in my life, coming out of college, truly confused,” says King. “So I thought that it applied.”

He spent five months hard at work inside the small building in Southwest Portland, demolishing the interior and refurbishing it with tables, a bar and a fresh coat of paint. King remembers wondering if anyone would come once it opened.

On 11:30 a.m. on Jan. 19, 1971, on his birthday, King opened the VQ to the public. To his surprise, 60 people had lined up outside his door, waiting to be served.

“The whole energy of downtown changed so much in the late 70s and early 80s. The high rises went up and all of sudden there are big firms and big companies. That had a lot to do with the evolution of the Quandary.” – Denny King

Originally, King planned on running the bar for a year, then selling it and moving to Paris. “Within a year,” recalls King, “it became so much fun.” But it wasn’t easy. King worked long hours, up to 20 a day, practically living in the bar.

“I had to go to the bakery, go to the butcher’s, clean the keg, clean the bathrooms, tend the bar, go sleep for a few hours and then do it again,” recalls King. “It was really fun because it was an endeavor. It was mine.”

Initially, most of King’s customers were his friends or fellow protesters, like PSU professors and students. “It was a place where like-minded people could enjoy the politics of the era,” he says.

But the VQ was also festive. “We would go to the park next to the restaurant and play volleyball, and we would invite other restaurants and bars (to) bring a team and play us,” says King.

Michael Hanlon, a lawyer who works downtown, has been going to the VQ for decades and is an old friend of King’s. He remembers it being a “typical college tavern” with a heavy dose of entertainment. Every Friday night at midnight, King would play Aretha Franklin’s “Respect.”

“It was a tradition,” says Hanlon. “People would rush from other bars at midnight. It was a rocking place. They would blast it and the whole place was singing along.”

On holidays, King would have the VQ donate a meal to a family in need. “Denny and I would pack up all the things that we would put together that we got from Costco or that the chef would cook,” remembers waitress Dale Maguire. “We would choose a family and make a Christmas or Thanksgiving for them. Money was never the object for that place.”

Maguire has been a waitress at the VQ since 1980. Besides King, she has worked there longer than any other staff member. She says King is an unusually kind boss, often encouraging his employees to move on to do bigger things.

In the late 1970s, the clientele began to shift.

“The whole energy of downtown changed so much in the late 70s and early 80s. The high rises went up and all of sudden there are big firms and big companies,” King remembers. “That had a lot to do with the evolution of the Quandary.”

The VQ was no longer a college bar. Instead, it became a hangout for lawyers, businessmen and politicians.

King still faced some rough patches. In 1987, business wasn’t doing well and King was prepared to close down. But what King describes as a “miracle” occurred. Peter Cook, a banker, lent him money to give the bar a boost. Within a couple years, things were running smoothly.

He had enough money to invest in a kitchen that turned the VQ into a functioning restaurant. Cook “was like an angel,” says King. “Why he would come, sit down and have coffee with me, I’ll never understand it.”

The VQ was stable for most of the ‘90s. But in 1999, there was a fire that damaged the infrastructure and completely destroyed the bar. “It broke my heart. I cried for half a day,” King recalls. “Then I started carrying out burnt wood. You just get right to work.”

All his time spent building up his business has cost King a stable home life. He’s been through three divorces, saying his devotion to his restaurant put a lot of strain on his marriages. If he did it all over again, King thinks the outcome would be the same.

“I would have stuck with the business,” says King. “Because without work, you don’t make it anyway.”

In King’s eyes, the VQ gives him a “purpose, and it identifies you. It is part of your personality. To give up your personality would be a mistake.”

But King still made time to be a father. Daughter Lindsey King remembers going to the VQ as a young child. “I knew all of the employees and I got to poach maraschino cherries from the bar,” she recalls. “While he worked, he would give me a flashlight and I would search underneath the bar and behind all the booths for quarters.”

Today, the VQ is wildly successful. King’s original three-person staff has grown to more than 70. The VQ now generates in four days the same amount of money it made in its first year, King says.

Inside the restaurant is a bubble of commotion. People file through the door, waiting to be seated. Waiters rush from table to table, serving food and drink. In the kitchen, cooks hurriedly prepare orders and the dishes are taken to the table.

On the patio, patrons bask in the sun, surrounded by the lush, kaleidoscopic garden. The Hawthorne Bridge towers above.

King has changed along with his restaurant. He seems to be more at peace. Although he officially works half days, he often stays for lunch. On some evenings, he goes to the bar for a drink.

Though King is aging, he doesn’t plan to sell the restaurant. “I am going to live it out because it is wonderful,” he says. “You get there and there is a line of people waiting for a table, and people are drinking in the bar and the dining room is full. It is just absolute poetry.”

He smiles and thinks about how far he’s come. “You feel so good about the whole thing. All the work, the years, have been worth it.” ♦