July 16th.

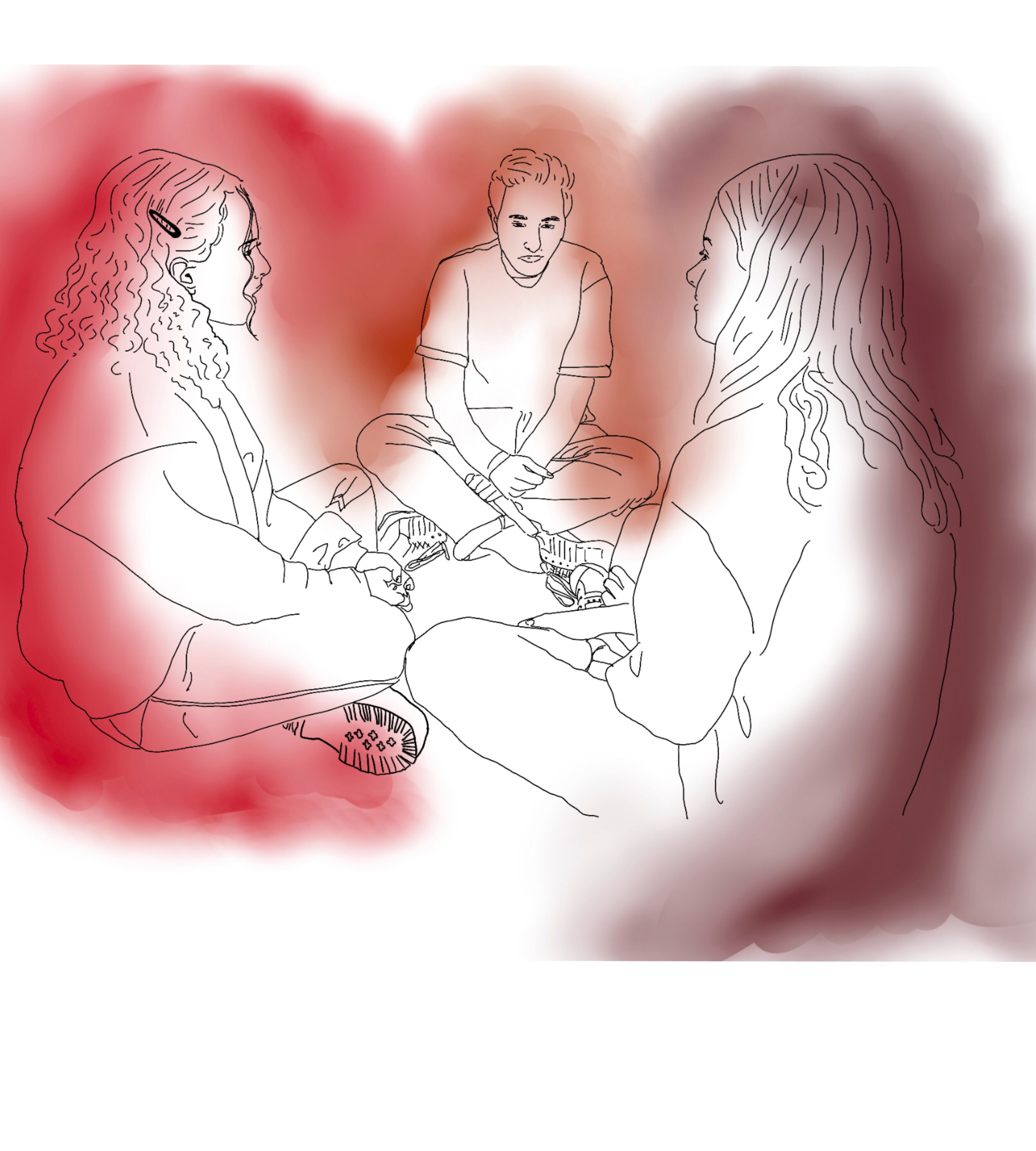

I rested my head against Emerson’s shoulder and felt the rumble of the words in her chest as they cascaded from her lips. I closed my eyes and let the words of “Goodbye Columbus” lull me into a half-sleep. We laid in my twin bed, cuddled together despite the thickness of the summer air. My curtains danced with the warm breeze and ruffled the stack of sketchbooks and loose drawings that cluttered my desk. As I listened to my sister read our bedtime book, I braided a strand of her hair.

At 13, I was a bit old for bedtime stories, but “Goodbye Columbus” was the exception. It follows the story of Valerie Rhode, an adventurous, independent and candid protagonist who decides to leave home on her 17th birthday to find her absent sister.

Valerie rides a Greyhound bus from Columbus, Ohio, to a worn-down bus station in Port Gibson, Miss. There, she is reunited with her lost sister.

Valerie was everything Emerson longed to be. She was fearless and determined. Outspoken, she voiced every thought in her head while maintaining a kind character.

“Goodbye Columbus” was Emerson’s prized possession. It became the centerpiece of her nightstand after reading it twice. When I turned 13, I convinced her to make it our new bedtime book.

Since before I can remember, we read a book together every night. She tried to show me worlds vastly unlike ours, with some relatable characters, and others who I never understood.

Each night, she would flip through the pages until she fell asleep, book in hand, softly snoring.

Tonight, however, we planned on staying up until midnight of Emerson’s 17th birthday.

Tired but content, we read late into the night, determined to finish the book.

Close to the final pages, she paused mid-sentence. Her abrupt stop jolted open my heavy eyelids.

“What’s up, Em?” I asked, poking her arm. She gave me a smile and giggled.

Turning onto her side, she grabbed my hands. “I wanted to tell you last week, but I didn’t know if I was going for sure.”

“Going where? Can I come?” I asked.

“I’m taking a Greyhound bus all the way to Port Gibson. Just like Valerie!” Emerson grinned.

My mouth hung open. “No way. Em, that’s awesome! Can I come with you? Please? ” I begged.

I knew that this was her book, but I hoped it could become ours.

Sitting up, she sighed. “I wish, Adriana. But this is a trip I have to do by myself. I’m leaving before dawn. I know Mom and Dad wouldn’t let me go otherwise. But maybe when you’re 17,” she said.

I tried to conceal my disappointment by hugging her. I buried my face in her shirt. My lip quivered, and I felt pools of tears form. I blinked hard to resist letting them stream down my face.

“Hey A, don’t be sad. You’ll have your adventures too,” she said, brushing a strand of hair behind my ear.

“Yeah, but I don’t want an adventure without you,” I said. Her wanderlust made me want to explore the world. If it wasn’t for her, I knew I would spend all of my time curled up in my room with a sketchbook.

“That’s sweet, but I’m not always going to be around. In a year, I’m going off to college. Soon you’re going to have to learn how to live without me, A,” she said.

I understood. This was Emerson’s story, a book that she had read countless times and been in love with since she first cracked open the cover.

I turned my head around to catch a glimpse of the clock: 11:59 p.m. “One minute!” I said to Emerson. I held her soft hands as we counted down from 60.

At 12:00 a.m. I whisper-shouted to her, “Happy Birthday!” and we jumped out of bed and danced around my room.

Twirling as if we had no control over our bodies, we fell over into a heap of tangled legs. Laughing, I looked at her and took a mental snapshot of her face.

With a quizzical look, she stood up and gave me a hand. Then, Emerson tucked me back into bed and pulled the blue sheets up to my chin. She kissed me on my forehead and whispered in my ear, “I love you, A. I’ll see you in a week.”

I hugged Emerson so tightly that she laughed. She brushed my hair back and stood up. In the doorway, she paused and turned to whisper to me, “Goodnight,” then quietly shut the door behind her.

I grabbed my sketchbook from the nightstand and began to draw us dancing in the middle of my bedroom. Even though it hurt that she was taking this trip without me, I could never really be upset with her for long.

“Only a week,” I said.

July 17th. Four years later.

Reflecting on my yellow walls, the sun peeks over the horizon. I watch the sky outside start to tint gray and orange. Slowly, the darkness seeps away into the trees.

This time of day was always Emerson’s favorite. The time of quiet and calm. She would say that she could hear the trees think.

I put on my yellow shirt and cowboy boots, formerly hers. Today, more than anything, I need her strength.

Gently, I touch the photos stuck in the edge of the mirror. One is a photo of my parents, Emerson and me standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon, another of us swimming in Lake Erie in the summer. But the one that makes me pause is a photo of Emerson and me on the first day of school, me starting second grade, her starting sixth.

Being a shy kid, I didn’t have anyone to eat lunch with, so I hid in the classroom during recess. Emerson found me curled in a ball under a desk, drawing with crayons.

“Whatcha doin, A?” she asked me, sitting down underneath the desk as well. “Mind if I draw with you?”

For the first two weeks, we spent every recess and lunch hiding out in the classroom until I mustered up the courage to face the cafeteria.

I smile at the memory, but, as always, it’s tinged with heartache.

Exactly four years ago, Emerson walked to the Greyhound bus stop on her way to Port Gibson.

But she never made it on the bus.

As she walked across 12th Street, she was hit by a semi truck. The driver fled the scene, and my sister died alone on the pavement, her blood spilled on the concrete, her yellow dress stained red.

They say it was a freak accident, but it’s hard not to have anyone to blame. The driver who struck and killed Em left before they could face punishment. And for no reason at all, she is gone.

I quietly pad down the creaky stairs with my bag slung over my shoulder. I’ve packed light, just the essentials: a change of clothes, my glasses and “Goodbye Columbus.” And, of course, my sketchbook, wrapped in yellow duct tape, and a graphite pencil.

Today, on the anniversary of Emerson’s death and what would have been her 21st birthday, I will finish the journey she started.

I peek into my parents’ room. I see my dad standing by the window, watching the sun come up. The glowing light sinks deep into the wrinkles on his face.

“Bye, Pops. Give Mom my love,” I say, and give him a hug.

“Be safe, A,” he says. I know he’s worried.

The brisk morning air feels refreshing on my face, and the morning sun warms my goosebumps. Walking down Town St., I cannot help but feel a wave of grief wash over me. The type of pain that flows through you from head to toe: aching and to the bone. There is no way to hide from the fact that Em died here. Even though it has been four years, it hurts as much as it did when we got the phone call.

I look both ways for cars and cross 12th St. The second I reach the other side, I can breathe again. I turn around and swear I see a flash of a yellow dress, but it’s just a flag outside of a storefront, fluttering in the wind.

My eyes peer ahead of me as I hear the Greyhound bus pull into the station with a gust of wind.

I board the bus, and find a window seat toward the back. As we pull away from the bus station, I only look back once. My thoughts are locked on what lies ahead of me.

I open my canvas messenger bag and retrieve my glasses, rest them on my sloped nose and pin back my long hair. The world refocuses, and I open “Goodbye Columbus.”

On the inside cover, I sketch a detailed portrait of Valerie. But my graphite pencil can’t capture her long black hair, striking blue eyes and yellow corduroy jacket.

I watch the towns and grasslands blur together and wish that I had Em beside me.

Staring out the window, I suddenly feel a presence in the seat next to me. Invisible, untouchable, but there.

“Honey, are you OK?” the woman across the aisle inquires. “Your face is white as a sheet!” I blink, and the ghostly presence is gone. I smile and nod. With a jolt, the Greyhound screeches to a halt. “Last stop! All of you folks get off my bus!” shouts the irritable driver. I pull my messenger bag onto my shoulder and shove the book inside. I clomp down the aisle and plaster on a smile as I exit the bus.

I step down onto the uneven sidewalk. “Made it,” I whisper to myself. I look around, hoping for a place to linger while I finish the novel.

Page 384. Valerie reaches her final destination: “The Gibson Grub Cafe.” She pushes open the glass door of the cafe, and her eyes meet her sister, sitting at a booth with a steaming cup of coffee.

Despite our similar ventures, I find it hard to come to terms with my reality. Valerie had the privilege of reuniting with her sister. She was able to hug her and tell endless stories from their time apart.

I don’t have that luxury. My sister won’t be seated at the Gibson Grub Cafe. No matter how hard I wish, Emerson will never again kiss my head, call me little sister or laugh at my immaturity.

I stroll through the streets, or more accurately, the one street of Port Gibson. I begin to feel a cramp in my right foot from my snug cowboy boots. Despite my discomfort, I will not allow myself to rest until I have arrived.

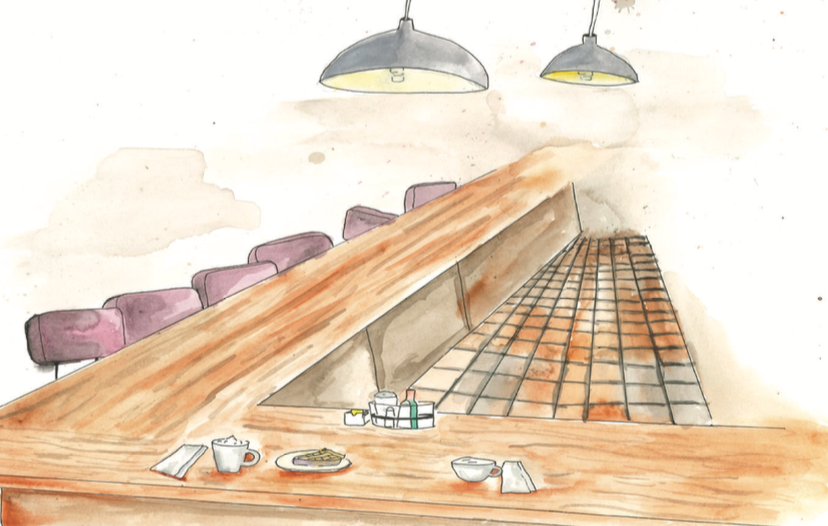

4:23 p.m. On the corner of Briarwood Road: “Gibson Cafe. Breakfast, Lunch, Coffee.”

I approach the door as I’ve envisioned hundreds of times. I grab the handle and push. It swings open and the tiny bell overhead jingles to announce my presence. The aroma of french fries and coffee fills the room. “At Last” by Etta James plays through speakers from the corner of the cafe.

I scan the ‘50s style eatery. The floors resemble my dad’s vintage chessboard, and the booths and bar stool cushions are tattered with age. An elderly couple in the corner looks up at me, but the rest of the customers seem more interested in their food.

Behind the counter, the waitress nods and asks what she can get started for me. I order a cup of hot chocolate and a piece of marionberry pie.

After I pay, I look around to find a place to sit. Despite my practicality, I cannot help but hope that by some miracle, Emerson will be seated at a booth, a cup of coffee in hand. But the booths are devoid of a curly brown-haired girl.

I take a seat at the bar and grab my sketchbook from my bag. I begin to draw Emerson, focusing on her delicate eyes and untamed hair.

On the other side of the L-shaped counter, a girl with muted black hair in a yellow corduroy jacket reads a comic book. She looks up at me, and my gaze meets her unflinching blue eyes. Her face is shadowed by her long hair, yet her features are clear and distinct.

I blink in awe as I stare at her.

Distracted by her familiarity, my hot chocolate slips out of my hands and spills onto the floor.

My clumsiness catches the girl’s attention. “I hate when that happens,” she says with a wide toothy smile. “Good thing you didn’t drop it on your sketch.”

I give her a shy nod and look back down at my drawing.

“Whatcha drawing?” she asks curiously.

“I’m drawing my sister.” Embarrassed, I look back down at my sketch. I continue, trying to draw Emerson’s crooked nose.

My focus is broken when I hear a quiet laugh. The laugh’s similarity to Emerson’s is almost uncanny. Startled, I peek at the girl around the corner of the bar. We make eye contact instantly.

“What’s so funny?” I ask.

“It’s hard to explain, this book is just hilarious,” she replies.

“It’s weird. Your laugh sounds like someone I know,” I say.

“Who?” she asks, looking intrigued.

“My sister Emerson,” I reply. I lift up my sketchbook to show her.

“Are you two close?” she asks, turning towards me.

“Yes. She’s everything to me,” I say, almost forgetting her absence.

“Is she here with you in Port Gibson?” she asks as she rests her chin on her hand. She seems genuinely interested.

“No, she isn’t,” I reply, breaking eye contact and looking back down at the drawing.

“So, what are you doing alone here?” she asks, ignoring my obvious discomfort.

I replay her question in my mind for a minute before I respond.

“For closure. I thought that coming to Port Gibson would help me make amends,” I say. I remember stepping off the bus just hours ago, and the hope I felt that somehow my sister would be here. That, in some way, she would show herself.

“I don’t mean to pry, but why are you trying to make amends?” she asks. It seems weird to tell a stranger the truth, but for some reason, I trust her.

“I lost my sister four years ago in an accident.” I set down my pencil and close the sketchbook.

“She always wanted to visit this town.”

Sympathy flashes across the girl’s face and softens her expression. She stands up and walks to sit on the stool next to me.

“That’s rough,” she says, “I know what that kind of loss is like.” She looks reflective, lost in her own past. “But, what made visiting this town so important to her?” she asks.

I pause. “Emerson was always the adventurous one. She wanted to be independent. She

wanted to see the world,” I say.

“Ah, yes. Independence,” she laughs. “That used to be my first priority.”

“This town was going to be the first stop on her journey,” I explain. “She never made it all the way, she never got the chance. So I wanted to try to complete her adventure.” I fiddle with my rings, avoiding her eyes.

“It seems like you might be trying to live her life instead,” she says bluntly.

“Maybe you’re right,” I say. “Emerson’s death left a hole in my life, and I’ve just been trying to fill it. I feel like everything I do has to be for her, because even after she’s gone, she’s still the most important person to me.”

She looks at me with knowing eyes. “You know, someday you’re going to have to start living for yourself again,” she says. “Your sister would have been proud of you for making it all the way here. But whatever you decide to do next, you need to get some independence of your own.”

I hope she’s right. I know the pressure that I feel to live my life to the fullest stems from

Emerson’s passing, and her loss of the chance to fulfill her many desires. But I can’t help feeling this way.

I look at her for a moment. Feeling more at ease, I squeeze her hand. “Thank you,” I say. I hop off the stool and place both feet on the cafe’s floor. Turning to say goodbye, I look back to the counter.

But my eyes meet only two empty seats. No coffee and no girl.

Gently, I set the book down on the counter, tracing the letters with my hand one more time. Perhaps someone else will read this story and it can help them find their way.

I nod, and under my breath, I whisper, “Goodbye, Valerie Rhode.”