Adrenaline races through the veins of firefighter Bradley Blocker as he arrives at a harrowing scene; smoke billows through the windows as a raging fire consumes a two-story house. Inside, a woman gasps for air, hangs her head through a foggy window as the flames approach.

Adrenaline races through the veins of firefighter Bradley Blocker as he arrives at a harrowing scene; smoke billows through the windows as a raging fire consumes a two-story house. Inside, a woman gasps for air, hangs her head through a foggy window as the flames approach.

Blocker rushes to the scene, hurls an industrial ladder to the ledge of the house. As the woman cries for help, looking as if she is just seconds from jumping, Blocker swiftly ascends the ladder.

In sheer panic, the woman climbs down the ladder face first, paralyzed by fear. As Blocker extends his arm to grab onto the victim, she loses her grip and falls to the ground. Blocker’s arm plummets with her.

“That was the end. That was the big injury that hurt my shoulder,” says Blocker.

In an instant, his firefighting career was over. After tearing every soft tissue in his shoulder, Blocker needed a complete reconstruction, making it practically impossible for him to do the job ever again.

The career-ending injury marked the end of a chapter in Blocker’s life. For over a decade, firefighting had formed an integral part of his self-identity, producing an unrivaled sense of purpose and fulfillment.

“Having been a firefighter, you’re always kind of trained to know what to do when something’s wrong, and so it felt very helpless to me,” says Blocker, who is now a teacher at Grant.

In a moment of uncertainty, Blocker turned to what he knew best: finding hobbies to fill his time.

Through childhood and adolescence, Blocker had turned to physical activities and sports to cope with family conflict and struggles in school. Yet after the injury, unable to fight fires or even be active, Blocker relied on newfound, unconventional hobbies for a source of fulfillment and personal growth.

“I realized the growth and it became infectious … Once I see growth … I want to feel that. I want to get better,” says Blocker.

As a child, Blocker was not initially interested in the idea of a career in firefighting. Coming from a third generation military family, in which his parents spent over three decades combined in service, his parents hoped that he would follow in their footsteps. Yet, after spending his early years on a military base in Germany and relocating to Eagle Point, Oregon with his mom, Blocker began to take an interest in a different area of focus: baseball.

After setting up a tee and mound in his backyard, Blocker established a consistent practice routine. When he was able to convince his brother to practice with him, the pair would spend hours on end playing catch. On other days, Blocker would simply throw a tennis ball against a wall and attempt to improve his skills as a catcher.

“It always felt like it was an expectation for me to be in the military, but when I was younger that wasn’t my drive. I was an athlete and I wanted to go to college and play baseball,” says Blocker.

Through baseball, Blocker also learned valuable life lessons such as dealing with losses and working selflessly on a team—skills that would be imperative in his future career.

“Sometimes you need to take the backseat to the greater outcome,” says Blocker. Even smaller elements of the game formed values that would stick with him for the rest of his life. “Later on I’ve kind of realized there are productive outs, there are productive failures I should say …. like a sacrifice but … you’re giving up your batting average in order to help the team,” says Blocker. “I think that’s a huge life lesson.”

Yet, Blocker’s childhood was not exclusively centered around baseball; in Eagle Point, Blocker also discovered a new hobby to channel his energy into, skateboarding. The activity provided him with an outlet to mitigate stress in challenging times.

“I was a big skater when I was in high school …. it was just somewhere I could disappear into, especially skateboarding you just go outside, put some headphones in, you have a rail and you’re just trying to perfect it.”

His connections in skating also introduced him to new pastimes like music and art. In high school, along with a few of his skater friends, Blocker began playing bass in a punk band. Despite palling in comparison to the vocalist and other instrumentalists in the group, he recalls thoroughly enjoying the change in pace.

Blocker says, “I picked up the bass pretty quickly and that’s when I realized like I might have a knack for guitar … it was mostly just for fun and hanging out. (Going) skating and then (playing) some music.”

Yet, his participation is these activities could not shield him from the obstacles in other aspects of his life. During his freshman year, Blocker dealt with a family conflict, resulting in missed classes and lost hours of instruction. The experience had a devastating impact on his grades and graduation prospects.

“It felt like I couldn’t catch up and so why try? It’s kind of the mindset I had in high school. It was an uphill battle and one of the darkest periods of my life, so it just felt unreachable, so I just stopped trying,” recalls Blocker.

During challenging days, Blocker turned to his pastimes outside of school for stability and fulfillment. “Baseball and weightlifting were my escapes, those were my escapes because I can go set up a tee and just go hit for hours and throw it against the fence and just work on my arm,” says Blocker.

However, struggling in school and other aspects of life, Blocker lacked purpose and an intention for his future.

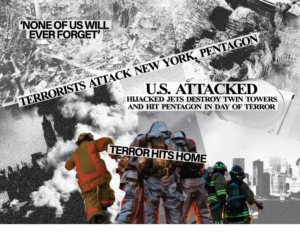

That all changed on Sept. 11, 2001. The day not only affected the course of his life but rather the whole world around him, giving Blocker a newfound sense of purpose that would carry on into adulthood.

‘We’re being bombed,’ Blocker’s mom said, racing into her son’s room.

It was 6 o’clock in the morning, around the time when Blocker, then a junior in high school, normally got ready for school. Blocker bolted out of bed and switched on the TV. He stared in horror at the scene unfolding 2,000 miles away.

“I woke up and I remember seeing smoke billowing from the building … in the shape of an airplane … it was very eerie. It didn’t seem real,” says Blocker.

While he surveyed the aftermath of the first crash, he saw a second plane come into view, its nose on a collision course with the second tower. Blocker watched in disbelief as the plane sliced into the building.

“Then you just see the blank stare of the firefighters, climbing the stairs … while everyone else is just trying to get out and they’re going up to who knows (what). They didn’t know (if) they were going to come out,” says Blocker. ”But you could see it in their face, they knew it was not okay.”

343 firefighters died that day. The number remained ingrained in his mind ever since.

The day forged a new world view for Blocker. At the time, he considered pursuing a military career to fulfill the wishes of his parents, but after Sept. 11, firefighting came into the picture.

While some of his peers waged a call for revenge and war, Blocker saw an immediate need in his community for protection and service—public servants willing to sacrifice their lives for a greater cause.

“That was life-changing for me, honestly. I was kind of a punk little kid at that time, not caring about school at all … it was kind of the first time that I felt like I had a calling … I felt like I had a purpose,” says Blocker.

While Blocker held on to this dream of one day becoming a firefighter, other priorities took precedent for the time being.

Due to the extent of his time away from school, Blocker was missing a considerable number of credits and his graduation prospects were grim. This not only threatened his educational opportunities but also his baseball career. After dropping out of high school in his senior year, Blocker lost his scholarship offer at a Division I school, UC Riverside.

“Losing the scholarship at that young of an age made things a lot harder. And (college) took me longer and put me into more debt,” says Blocker.

After high school, Blocker faced a harder route to receive a college education and play athletics. He enrolled in a community college to get his general education diploma (GED), later transferring to Montana State University to play baseball.

Throughout college, Blocker remained undecided about his future, changing colleges and majors repeatedly. However, during this shifting period in his life—with his firefighting dream on hold—athletics remained a constant.

Through baseball, Blocker not only found a supportive community on campus, but it also allowed him to realize his full potential and foster the work ethic and drive required to succeed as a firefighter.

“Out of high school, if I tried going into firefighting at that time, I probably wouldn’t have made it. It took a lot more work to get to that higher level, and kind of realizing that you have to push yourself in order to get what you want out of it,” he says.

After finishing up his degree in pre-therapy at Oregon State University, Blocker began applying to graduate schools along the West Coast. Yet, he felt a piece of himself was missing; the childhood dream of firefighting lingered in his mind.

While working as a personal trainer and fitness instructor at a local gym in Corvallis, an opportunity arose. Blocker struck up a conversation with a customer and close friend who happened to be a firefighter at Salem Fire Department. After discussing the job for hours on end, it became apparent that his dream to become a firefighter was indeed plausible.

“As soon I realized that it was attainable, that’s all I wanted to do,” says Blocker.

After he quit his job as a personal trainer, Blocker began to work as a resident intern firefighter in Polk County, spending his days and nights in a firehouse.

Living with eight other firefighters, three to a room, the job posed quite an adjustment at first. Blocker had to be ready to pull on his gear and go on call at a moment’s notice. Shifts sometimes extended as long as 72 hours.

The nature of the job was also highly variable and subject to change by the day. While the majority of calls were medical, one might never know when a fire call would throw a jumble of departments into action.

Despite the danger and potential for injuries, Blocker lived for the fire calls. “The actual act of fighting a fire is really fun. There’s a lot of moving parts that have to come together … and then you have to be all in unison working together cohesively for the common goal, and that’s kind of beautiful to be a part of,” says Blocker.

Regardless of the long hours and sleep deprivation, Blocker embraced the adrenaline-rushes and spontaneity of the job. While the time commitment of the job meant that Blocker was not able to continue playing baseball, firefighting provided aspects of athletics that kept up his motivation.

“Running calls, you get a workout in every day, you drill every day, which … it was kind of like being in athletics again … it’s very family-oriented … You work out together, you eat together, you drill together,” recalls Blocker.

Unlike other times in his life, Blocker had a support system and family to turn to during challenging days. The comraderie of firefighting was a tremendous aspect of the job, and allowed the station to come together and work as a unit.

Blocker says, “We call mealtime family time and we take it serious, like you do not get up from family time. If you’re the first one to get up and put your dish away and no one is done eating, you’re going to get yelled at. You sit there and you build together … you build the camaraderie.”

After his years at Polk County and spending time as a paramedic with Pacific West Ambulance, Blocker applied to Tualatin Valley Fire and Rescue, which at the time, he recalls as being one of the most competitive fire districts around the country. After a thorough interview process, Blocker got the job.

The real challenge would lie ahead in training. While in his probationary period with Tualatin Valley, in a boot camp known as the “Recruit Academy,” Blocker suffered a serious shoulder injury on the job. Blocker recalls that it was one of the most grueling experiences in his life to tough out the injury.

Yet, around four months into the job, things began to look up when he met his future wife, Charlotte Blocker. She not only provided him with day-to-day encouragement, such as packing large lunches for Blocker on work days, but also with lasting support to help him preserve in the Academy and the years to come.

“He had just been in academy for a month or so when I first met him. Academy was really hard on him … . I remember one day he was gone for 16 hours … and he came home and he had heat rash on his ankles, wrists and elbows …it was really hard,” says Charlotte Blocker.

Despite the difficult experience in the academy, Blocker recalls thoroughly enjoying his time at Tualatin Valley. The action-filled days and the community were all rewarding parts of the job. Yet, for Blocker, the utmost fulfillment arose from serving the community. By spending the better part of a decade saving lives and helping others, Blocker had accomplished his childhood dream.

“What drew me to the job definitely was the sense of service … it definitely felt like I was being part of the community in a job that needs to be done,” says Blocker.

Eventually, the strain of the job and his past injuries caught up to him. After the career-ending accident, Blocker’s firefighting career had come to an end. Blocker’s source of purpose and gratification was gone and he would have to find new, unconventional ways to live contently and reconstruct his identity.

Five days after the surgery on his shoulder and just over a week since he last wore his now lifeless uniform, Blocker lied motionlessly on a snug couch as thoughts raced through his mind. He attempted to lift his forearm but was unsuccessful. He sat in anguish as the throbbing pain swept over his body. Firefighting, baseball, anything remotely physical, was a distant memory.

As he sat in silence, Blocker contemplated how his life has changed in a matter of days. It was just around the time when he was usually on call, sitting with his fellow firefighters at the communal breakfast table, anxiously waiting for the inevitable medical call or fire. Yet, Blocker was home—constrained in a cast.

He knew that the accident was almost certainly the end of his career, yet he struggled to acknowledge this new reality.

“I chose to accept (it) and I think that’s when I realized … I (needed) to find other hobbies … and I feel like I did it out of necessity just for my mental state … without that, I feel like I would have just crumbled in depression because my identity was kind of lost,” says Blocker

In a moment of uncertainty, Blocker picked up an untouched guitar and began strumming chords. With his arm restrained by a sizable cast, his motions were labored at first. Yet, he persisted, plucking a C to an F, then a C to a G, gaining strength and intensity with each strum.

Over the next few months, he would spend the hours fiddling time away, concentrating intently on the tone and timbre of the instrument, taking his mind off the difficulties surrounding his new reality. Guitar not only provided Blocker with a tool to channel his energy, but it also served as physical therapy, allowing Blocker to rehabilitate the muscles in his arm.

Despite successfully finding other hobbies to fill his time, the pain from the injury and his longing for physical activity consumed his thoughts. After spending two decades centering his life around physical activity and sports, a sedentary lifestyle posed a significant challenge for Blocker.

“I thought for sure that this was going to be the thing that got him down because … all his hobbies were just like taken away from him. His career was in the balance. I mean, it was a really uncertain time. And Brad just can’t do nothing,” says Charlotte Blocker.

In need of other hobbies to fill his time and distract from the day to day toil of the injury, Blocker experimented with other activities like acting. While he was originally apprehensive about speaking in front of others, he eventually overcame his stage fright and improved at public speaking.

“I’ve always had an appreciation for the arts, but I’ve never dove into it, so after my injury, I really tried to dive headfirst into anything I could like that. I (needed) something to focus on. It was a year and a half recovery, so it was a long time. It gave me a lot of opportunities to find new passions,” says Blocker.

During the recovery, Blocker was still employed by the fire department and spent a few months working a desk job for the station. Yet, after months of strenuous physical therapy and Blocker’s unrelenting efforts to return to the job, it became apparent that he would need to change his career.

Blocker initially struggled to find a job in the public service field that interested him, especially since he imagined himself as a firefighter for the rest of his life. However, when teaching came into the picture, he latched onto the idea and remained set on that path.

“I think choosing to teach was pretty easy for Brad. He had been a personal trainer at one point. He likes interacting with other people. And I think he has a strong sense of social responsibility about his choice of what to do in life,” says Charlotte Blocker.

After officially parting ways with the fire station and finishing his master’s degree at Concordia University, Blocker landed a job at Grant as a part-time health teacher.

The 2019-20 school year has not only marked Blocker’s first year at Grant, but his first year of teaching ever. While Blocker has experienced a considerable learning curve, his experiences in other areas have provided him with guidance and confidence.

“I’ve never liked talking in front of a class and I really feel like acting really made me way more comfortable in this career as a teacher … I always used to be so nervous with that, but after the acting classes, it was mostly just gone,” says Blocker.

As a teacher, Blocker hopes to share his journey and past experiences with students to help them reach their full potential. After his tumultuous period in high school in which he lacked both stability and a support system, Blocker wants to be an advocate for struggling students

“You still have to try and achieve and grow during a rough patch in your life … I’ve always wanted to be the advocate for students … who are struggling … kind of show (them) that … it isn’t the end of the road and you don’t have to do it all or know it all in order to change for the better,” says Blocker.

Last year, Blocker also stepped into the role as an assistant coach on the Grant baseball team. Blocker hopes to share his passion for sports and use it to better the lives of the next generation of athletes, and aims to use sports as a medium to teach life-lessons like learning to rise above defeat and to use failure as a means of growth.

“When you’re talking with him … he’s invested with that moment … you definitely feel like a strong connection and he’s just really friendly and puts others at ease. And that goes with students, parents … and also just like other coaches … his personality just lets him join and contribute to a group in a really natural, easy way,” says Grant baseball coach Matt Kabza.

After a series of trials to get to where he is today, Blocker feels fortunate to be at Grant. While he once envisioned himself fighting flames for the rest of his life, his memories remain with him, entrenched in a self-identity reconstructed time and time again. While Blocker remains uncertain for what the future may hold, he hopes to continue to pursue the hobbies and experiences that got him to where he is today.

“I really admire that quality in Brad that got him to look into acting and to learn to play guitar, like that part of him that is always looking for something to do,” says Charlotte Blocker. “It’s a really admirable quality and … he’s always looking for something to do with his time that he loves.”