*Sensitive Content Warning: Rape, sexual assault and harassment.*

Just before the turn of the century, David Lickey faced a difficult decision: move to Eugene, Oregon, to take the teaching job that had been his goal for over 10 years, or stay in Portland with a woman he had been on two dates with.

Lickey first dreamed of becoming a teacher while at National Guard training camp in the mid-1990s. He had always been fascinated by the military and resolved to join after high school, but was rejected. It was only after obtaining a history degree, while loafing around Eugene, that he stumbled upon a second chance at military greatness when he passed a Guard office on his motorcycle and decided to apply.

The National Guard was a turning point for Lickey. “I learned … something which I had not learned in life before which is discipline, how to control myself,” he says. He also learned to look at his life realistically. “You have a lot of time for introspection,” says Lickey, “When you’re in an unpleasant place for a long time.” He decided teaching was something he could “probably realistically do, and do well.”

Lickey has what he calls an “intellectual personality and turn of mind.” He only needed an authoritative push to get the wheels rolling — wheels that would drive the rest of his life.

In his last year of service, Lickey worked for the Bureau of Land Management, catching illegal marijuana growers. To pass the hours, he read voraciously — one to one and a half books per day. He would scour the literature section of the Smith Family Bookstore in Eugene for any title he recognized. “I read over 100 books of canonic literature that summer,” he says.

Lickey’s passion for history began to take shape in junior high school when he read Erich Remarque’s “All Quiet on the Western Front,” a book that profoundly impacted his life. Originally, Lickey felt no draw to higher education. He couldn’t compete with his Stanford-bound step-sibling, so he looked to create a new identity in the military.

“It was kind of an act of rebellion because I was a bad student,” he says, “I would do something better, something more bold, more epic.”

Lickey’s raucous youth caught up to him. His copious smoking weakened his lungs; he failed the Army’s fitness test. Defeated, he relented on going to college. He tried the University of Cincinnati but got homesick and transferred to the University of Oregon.

There, Lickey became enthralled by George McGowan’s Western Civilization lectures, admiring his ability to deliver ideas. He resolved to teach in Eugene like the educators that shaped him, but there were no open positions. Lickey moved to Portland, where he planned to work at Grant for a few years until a job opened in Eugene. Four years later, he was offered such a position.

Then he met a woman named Kathryn Short. They had only gone on two dates, but Lickey could tell that if he let her go, he might regret it for the rest of his life. The only issue: Short refused to move to Eugene. Late August was approaching, and Lickey had to make the most important decision of his life: Take his dream job or stay with a woman he barely knew and hope.

He stayed.

“The best and most important thing in my life, one thing that’s gone the best for me, and why my life is so good in so many ways,” says Lickey, “Is because of my partnership with Kathy.”

Over two decades later, Lickey still teaches at Grant. He has a profound belief in the importance of studying history and literature. He uses historian and educator Paul Gagnon’s idea that historical study builds an individual’s judgment and wisdom about human society, and Mark Twain and historian Margaret MacMillan’s belief that “history never repeats itself, but it often rhymes.”

Lickey advocated for the teaching of courses like Modern World History, Advanced Placement (AP) European History, and AP United States History at Grant. His passion for teaching history is evident: he crossed and recrossed his legs in frustration and tapped his well-worn penny loafers against the air — as though he wished to pace but felt it rude — as he described how U.S. History and Modern World History were both replaced with less history-based courses.

He assigned me readings in our interviews — from comparisons of pre-World War I and early-21st-century Europe to arguments for high school and college history classes. He asked me about my takeaways from Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” and recommended a variety of books. He is always teaching.

Lickey describes his teaching style as inherently self-serving. “I don’t think that I’ve been (or) that I’m a particularly skilled instructor. In fact, I know I’m not,” he says, “I’m not motivated by the ability to forge meaningful sort of personal connections with students.” If he does form such a relationship, it will be through “sheer engagement around ideas and the fun and excitement of them.”

Lickey sees “moral and ethical sensibilities in the profession” and the “danger of activism in education,” which he considers an abuse of power. “A teacher should try to complicate, should try to make things difficult,” he says, “Not to give (into) ideological, dogmatic moral impulse, which is easy.”

In 2017, Lickey proved himself right. Fellow humanities teacher Dylan Leeman was holding a discussion with his class on rape culture — the idea that society trivializes and normalizes sexual assault and harassment — when Lickey, who had entered the classroom to make photocopies, added that he didn’t believe in the concept. He left and later apologized to Leeman for disrupting his class, but his colleague lamented that Lickey hadn’t stuck around to explain his thoughts.

In a three-page letter addressed to “Esteemed Students and Mr. Leeman,” written on May 2, 2017, Lickey did just that.

He outlined why he found “assertions of rape culture dubious,” saying the concept was ill-defined, that rape was generally understood to be a heinous crime and that rates of rape and sexual assault were declining. He ended the opinion piece by saying he would love to hear the thoughts of any who disagreed.

He sent the letter to Leeman. “I’ve shared that with no student,” Lickey told me, but said it was “absolutely welcome” to be. Leeman handed out copies to the class that Lickey had conversed with, one of whom showed it to a parent, who then posted it on Facebook. The backlash was staggering.

The Oregonian, Grant Magazine and even a British tabloid, The Daily Mail, covered the ensuing outrage. Students and teachers picketed outside Grant; former Principal Carol Campbell condemned the letter. In a single flare, the previous two decades of Lickey’s life looked on the verge of collapse.

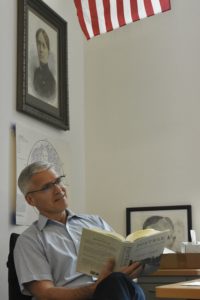

He spoke remorsefully to Grant Magazine of his wrongdoing and what he had learned from his mistake. He even posed for a desolate photograph in the hallway, shirt wrinkled, crew cut anxiously disheveled.

Five years later, the scars remain. “That was the end of my career,” he says, “I haven’t felt like — I don’t feel like a natural part of this faculty or community since then.”

According to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), one in six American women experience an attempted or completed sexual assault in their lifetime, and 82% of juvenile victims and 90% of adult victims are female. Lickey wrote that “women are safer on (college) campus(es)”; while female college students ages 18–24 are three times more likely to experience sexual violence than women overall, per RAINN, those women are 20% less likely to experience sexual violence than women of their same ages who are not students.

His continuing anger primarily stems from a feeling of mistreatment. He acidly recounts that students accused of rape were not disciplined by the same Grant administration that “attempted to sanction” him. “When it comes to rhetorically defending people from oppression, you’re gonna run into people over words,” he says, “When it comes to actually defending people, you’re too cowardly to do it. And that to me is inexcusable.”

He defended his thesis as “entirely arguable” and spoke of famous historical heretics, including Socrates, Martin Luther and Jesus. “What I learned was that there has been a shift and that my view of the world and that of the community, which I serve, was not in sympathy as I understood it to be,” says Lickey.

Lickey plans to retire after the 2022–2023 school year. Central to this decision is the alienation he has felt in the Grant community since his letter was shared widely in 2017. “It’s not a healthy fit,” he says.

In retirement, Lickey wants to be a “bon vivant” — a “good liver.” He’s considering returning to Grant for the occasional substitute teacher gig but primarily wants to enjoy himself.

“That was good for me,” he says of three decades in education, “I hope you learned something.”

A previous edition of this article was misleading in its placement of a statistic that said women attending college are three times more likely to experience sexual violence than women in general. Women ages 18–24 are more likely than women overall to experience sexual violence, but are 20% less likely to experience sexual violence than women ages 18–24 who are not attending college.