On a Thursday in February, four Grant High School students approached a freshman after school and demanded money. One of the assailants pulled out a knife while another searched the victim’s pockets for cash.

According to court records, the boys surrounded the victim but soon found he didn’t have any money. So they walked away, reportedly laughing about the confrontation before heading to a nearby McDonald’s.

The next day, the victim told his mother and she contacted police. Meanwhile, the four assailants went through the weekend without giving the incident much thought. Within eight days, they were arrested, taken into custody and charged with six counts each of first-degree and second-degree robbery.

In Oregon, those charges carry a hefty weight for anyone convicted of them: seven years, six months and five years, 10 months, respectively. The crimes are part of a list of violent offenses that fall under Measure 11, an Oregon law that metes out mandatory minimum sentences.

That means for minors, they face the possibility of getting tried as adults and serving hard time.

“It has a huge impact on young people’s lives,” says Kate Desmond, a manager with Multnomah County’s Department of Community Justice. She supervises nine probation officers at the Gresham office, including one who carries the juvenile Measure 11 caseload. “I really don’t think that the public is aware of Measure 11,” Desmond says.

Under the initial charges, each of the boys – who are sophomores and juniors – faced serious jail time. They were booked into the county’s Donald E. Long Juvenile Detention Center for more than two weeks while they awaited pre-trial hearings.

Now, roughly two months later, they pleaded no contest to the charges and will be serving three years of probation.

Data collected by both the Oregon Justice Resource Center and the Oregon Justice Commission shows that since its inception in 1995, more than 4,000 juveniles in Oregon have been charged in adult court system, making up roughly 10 percent of the total number of people charged with the crimes. More than 1,200 of those were charged in Multnomah County.

For more than 20 years, the statute has remained the subject of heated debate, with sides arguing for its necessity or its reform. Still, many people are in the dark about the measure’s complex nature and lifelong implications – in particular, high school students.

Charlie Tzab, 16, was one of the four boys charged in the crime. In an interview, he says he wasn’t aware of Measure 11’s sentencing provisions prior to getting arrested. “I didn’t really know anything about it before,” says Tzab, who was one of two from the four who agreed to talk to Grant Magazine. “At Donald E. Long, they just explained it to us…It was really stressful and surprising and confusing at the same time.”

Tzab isn’t alone. How Measure 11 works is complex, at the least. And under its weight, defendants can see lengthy sentences that can alter their futures.

Oregon voters approved Measure 11 with 66 percent of the vote in 1994. The measure requires minimum sentencing for specific degrees of violent crimes, such as rape, murder, arson and robbery. Those convicted of a Measure 11 crime, starting at age 15 or older, are tried in adult court and are subsequently transferred out of the juvenile system.

“Mandatory minimum sentences are an example of what seemed, to some, like a good idea at the time,” says Aliza Kaplin, the president of the Oregon Justice Resource Center. “Effectively, there’s no opportunity to consider the individual circumstances of a crime or a defendant when a mandatory minimum sentence is imposed for certain crimes…their sentence has already been decided behind closed doors.”

In the time leading up to the November 1994 election, the United States saw unprecedented levels of violent crime, and national media outlets focused particularly on youths who were involved.

Steve Doell, a proponent of Measure 11, describes the time period to be a turning point for teenage crime across the country. “In the late 80s and early 90s, there was this change in the makeup of the teen population in which we saw teens doing things that we hadn’t seen them do before,” says Doell.

Before, he says, “It was very rare that you would see a teen involved in a murder or a teen involved in a vicious or forcible rape.”

And when cases like those happened, many times they were pushed to the forefront of media coverage, sending a message to the public that crime had spiraled out of control. Doell also has a personal connection. In 1992, his daughter Lisa was struck and killed by a teenage driver in Lake Oswego when she was 12. The 16-year-old perpetrator was charged with manslaughter and served only 28 months behind bars.

Doell channeled his heartbreak and anger into action. He got involved with the campaign for mandatory minimum sentencing, becoming one of the go-to advocates for Measure 11. He recalls many high profile Oregon cases, on top of his daughter’s, that have helped fuel his efforts. One involved a teen who was given 18 months in prison after raping a 3-year-old girl and brutally assaulting a man.

Such cases received heavy media coverage. Some believe the media was sensationalizing things, using high profile cases to pass judgment on an entire generation.

“The examples that people always use are the most egregious examples…They use these kind of ‘super-predator’ characterizations of young people. But, you know, what this has done instead is it’s locked up first-time offending children – disproportionately children of color – and committed them to a lifetime in adult criminal justice system,” says Roberta Phillip-Robbins, who works part time as a youth and gang violence prevention specialist in the juvenile service division of Multnomah County’s Department of Community Justice.

Phillip-Robbins is also running for Portland’s House District 43, representing North and Northeast Portland and says that one priority of her campaign focuses on criminal justice reform. “We have to talk about what it means to lose 60 months when you’re 15,” she says. “What kind of adult and community member are we hoping to get out of locking a child up at 15 years old?”

Ultimately, Measure 11 was created with the intention to decrease crime and curb recidivism. It was often presented as a fear tactic to use against youth, pushing them away from a life of crime.

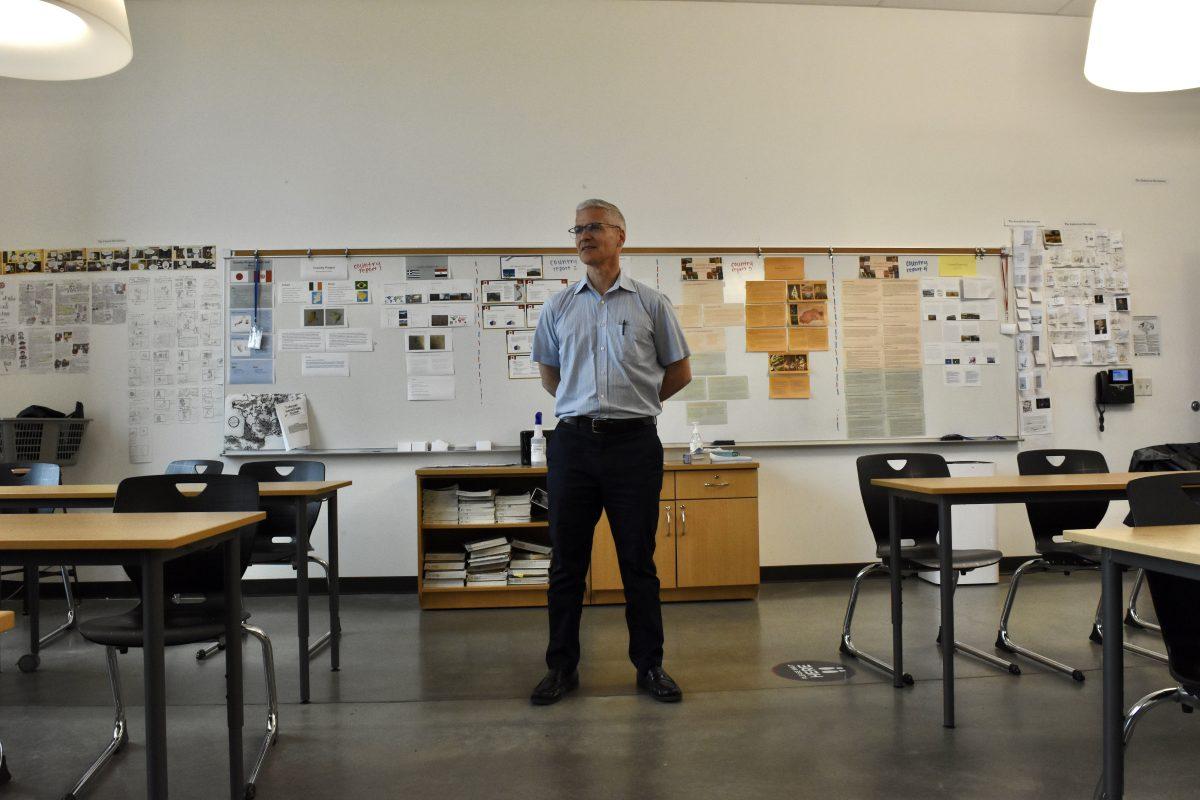

David Lickey, a Grant social studies teacher, remembers when a police officer came to school in the mid-1990s to explain Measure 11 to students. The message the cop delivered being something like: “All you little cretins better be good because if you screw up now, we are going to send you to the state penitentiary for a long time.”

“He had the stage set up with the flashy red and blue warning lights,” Lickey recalls. “And he was not well-received. It seemed to me that the police officer was going to turn a school assembly into a riot because he was so aggressive (in) rolling out this policy.”

When it comes to Measure 11, a large percentage of individuals charged under the law accept some kind of plea deal. But it can be difficult to escape incarceration.

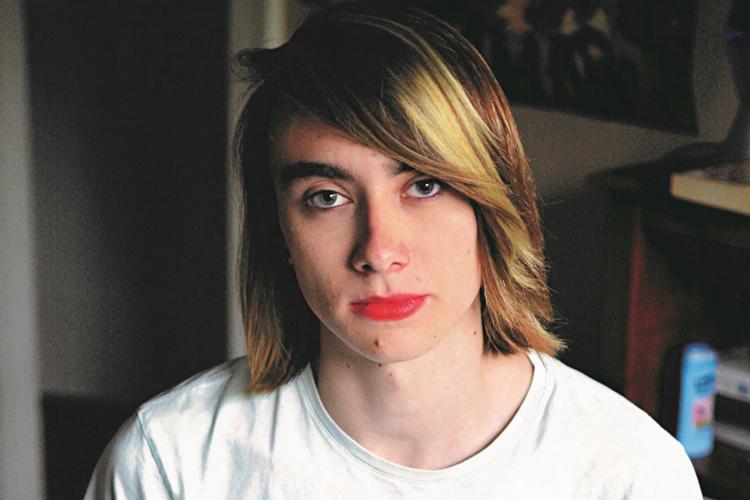

Noah Schultz is currently serving the last six months of a 90-month sentence after he was convicted in 2009. Schultz grew up in Southeast Portland and was involved in gang activity from a young age. When he was 17-years-old, he says he was robbed during a drug deal gone bad.

In an attempt to get his money back, Schultz assaulted his alleged attacker, then turned himself in to the authorities. His actions landed him in court on a slew of charges, which were later changed to first-degree assault. He has spent the last seven years in various facilities and says the experience has been transformative.

“I’m kind of one of the people who makes the best out of any situation, you know?” he says. “I’ve learned that through this, so none of my time has been wasted.”

While he has been incarcerated, Schultz, 24, has earned his high school diploma, an associate’s degree, two bachelor’s degrees from Oregon State University and is currently studying social innovation through Portland State University. “This has been a good thing for me in some ways,” he says. “But that’s because I lacked structure in my life. So what kind of preventative services could we be offering to give kids, who are a lot more at-risk, the kind of structure that they need to succeed?”

Still, speaking from firsthand experience, Schultz emphasizes some of Measure 11’s more adverse effects on young people who get convicted.

“You witness quite a bit of violence when you’re in institutions…and the youth system’s a lot different than…the adult system,” he says. “As humans, we are meant to connect with other people…Facilities cut that off, and a lot of people…come out really awkward.

“They don’t have the chance just to interact socially. And when they’re coming in at such an early age, they don’t know how to act in adult situations.”

In the case at Grant, the four assailants were able to plea to crimes that didn’t involve serving time. Prosecutors ultimately offered them two options: try to fight the case in an adult-court trial and risk being convicted or plead no contest to a lesser crime and get off with three years of probation and a criminal record.

The boys and their families say they had little choice; each accepted the plea deal, along with a strict set of conditions. Until 2019, they are collectively prohibited from interacting with one another, both in person and over the Internet. They each have curfews and are restricted from leaving Oregon without pre-approval.

If any of the boys commit a crime before they’re off probation, they could be subject to additional charges and jail time. Only at the end of three years would they be able to get their criminal records expunged.

“The authorities, anybody in a place of power, if they can put you in a box they will,” says Saadiq DuCloux, 17, one of the boys involved in the incident at Grant. “People need to know that (Measure 11’s) out there and the severity of it. I just felt like it wasn’t told to me…enough to ward me…away from the behaviors of it…‘Don’t do dumb things, don’t be an idiot.’ And that’s…what I was at the time.”

“Let’s be brave enough to talk about, ‘Did it work the way we hoped?’”- Roberta Phillip-Robbins

Plea-bargains are a common practice under Measure 11. But Multnomah County District Attorney Rod Underhill notes that plea negotiations are a tactic used commonly within the criminal justice system. In fact, he says, upward of 95 percent of all cases in the system, not just Measure 11 cases, are resolved through plea bargains.

Age, offense, criminal history and risk to reoffend are just some of the factors that prosecutors consider on Measure 11 cases. Underhill adds scientific study to the list. “At 22, there’s a lot of neuroscience that (is) telling us the brain is not fully formed,” he says. “And we need to make sure that we’re putting both variables into our assessment of what is the right thing to do.”

Schultz echoes Underhill’s sentiment. “You really need to look into brain science when thinking of giving juveniles adult sentences, which will later give them adult felonies,” Schultz says. “If you’re gonna give a 16- or a 15-year-old an adult felony, that’s gonna stay on their record…which then alienates them from job opportunities, career opportunities, travel opportunities, so many different things, all for a mistake they made when they were underage.”

Luis Tzab, Charlie’s father, believes more of an effort should be made making sure young people are aware of Measure 11’s consequences. If educated on the statute’s provisions prior to an offense, Tzab thinks kids would be more likely to “think twice before doing something stupid.”

Shortly after word of the attempted armed robbery hit the Grant community last February, many jumped to conclusions – including local news media outlets. Errors in the students’ names, ages and racial backgrounds appeared in stories published soon after the incident occurred. Hateful comments also followed the articles, many of which were blatantly discriminatory.

Fidel Cassino-DuCloux, Saadiq’s father, works as an assistant federal public defender in Portland. He says the negative commentary is to be expected.

“The same people always comment on these cases and the comments are all the same,” says Cassino-DuCloux. “They are all racially motivated; they’re all mean spirited.”

Internet comments aside, members of the Grant community reacted to the incident. Many students expressed empathy for the boys on social media, while others felt they deserved the initial sentences they faced.

Fischer Jemison is also a senior at Grant. He says he sympathized with everyone involved. “I kind of felt bad for the student who had gotten mugged and I was kind of surprised that it happened,” he says. “I don’t know, it felt kind of distant. I do remember thinking that some of the charges seemed extreme. My initial impression was it seemed like ruining your entire life for something that was kind of a dumb mistake.”

As per the conditions of their probation, only two of the four boys were allowed to come back to school at Grant after their pleas were reached. The victim stayed at Grant and declined to be interviewed for this story. The other two boys were provided with alternative schooling options for the rest of the year. It’s unclear whether they will return to Grant.

While the four assailants are adjusting to life on probation, the Measure 11 statute still stands steadfast in Oregon, with scant legislative moves toward reform.

Still, many continue to advocate for its reconstruction or, in some cases, complete elimination from the Oregon justice system.

“I would like to talk about the unintended impacts of Measure 11 in our communities,” says Roberta Phillip-Robbins. “In 1994, when people passed this, they had the best of intentions; they wanted safer communities. Let’s be brave enough to talk about, ‘Did it work the way we hoped?’

“And if it didn’t work the way we hoped, we have a responsibility to do the right thing, which is to change our practice if we know it’s not getting us the results that we hoped for.” ◊

Grant Magazine staffers Dylan Palmer, Toli Tate and Joshua Webb contributed to this report