The sun is shining on a clear fall day as senior Skylar Pierce-Smith sits in a Portland Police Bureau patrol car. Grant High School’s Resource Officer, Deshawn Williams, takes the wheel as they drive down Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd. Pierce-Smith watches as cars immediately slow to five miles under the speed limit as the cop car comes into view. The computer on the dashboard lists plates and names of drivers that pass by.

Pierce-Smith sits shotgun, rather than in the backseat like many other black Americans due to racial disparities and mass incarceration in the United States.

Youth of color are far more likely to be arrested than white youth. Between 2003 and 2013, the racial gap between black and white youth being arrested increased by 15%. And as of 2013, black juveniles were more than four times as likely to be committed as white juveniles.

Pierce-Smith has pictured herself in a police car for years. Not because of these statistics, but because she wants to help and protect others. Growing up multiracial, Pierce-Smith struggled to find her identity and a sense of belonging. The Portland Police Cadet Program has given Pierce-Smith a platform to help kids dealing with similar experiences.

But helping others took on another face for Pierce-Smith in 2015 when she exchanged her cadet cap for a tiara, her uniform for a turquoise two-piece full-length dress and her heavy boots for shimmery high heels. For Pierce-Smith, being crowned Miss Black Oregon Talented Teen holds the same meaning as riding in the passenger seat of a police car.

“I have always wanted to be the role model for someone, and to put a face on what a young black girl’s future could be,” says Pierce-Smith. “I want to be someone who is there to help the community.”

On Aug. 2, 2000 Skylar Pierce-Smith – who identifies as black, white and Middle Eastern – was adopted from Texas at the age of two months by Melissa Pierce and Luke Smith, both white.

As a child, Skylar Pierce-Smith loved to dress up as Belle – her favorite Disney princess – and put on shows for her parents, reenacting scenes from movies or making up plays herself.

When Pierce-Smith was 5 years old, the family adopted another daughter named Maya, who is Hispanic.

Living in a family with different races, Pierce-Smith grew up valuing uniqueness. The Metropolitan Learning Center, where Pierce-Smith attended through 7th grade, helped ferment the values of community and family that her parents instilled in her from a young age. The caring and nurturing environment allowed Pierce-Smith to feel comfortable trying new things.

Pierce-Smith took every opportunity her school had to offer. She enjoyed the annual Winter Solstice performance as well as the talent show, continuously striving to push beyond her comfort zone.

While Pierce-Smith never felt different than anyone else, at the start of 6th grade she started to feel insecure about what she looked like. Though MLC was friendly, relaxed and an overall enjoyable experience for her, the start of middle school gave Pierce-Smith something she didn’t have before: the perception of race.

“Girls would ask, ‘How does your hair get so curly?’” says Peirce-Smith. “I realized I didn’t look like them at all. I didn’t have pale skin or straight hair.”

Suddenly Pierce-Smith found herself struggling to fit in.

In order to come to terms with who she was, Pierce-Smith began to look into her culture’s history. She found the movie “Boyz n the Hood” and hip hop music. Pierce-Smith started talking in African American Vernacular English – the informal speech of many black Americans.

As Pierce-Smith was exposed to AAVE more and more through movies and music, the way of speaking began to feel natural.

“My white friends would notice when I talked in (AAVE) and would ask, ‘Why are you talking black all of a sudden?’” says Pierce-Smith.

She no longer felt like she belonged in the community she once believed was accepting.

“It was a struggle for her,” says Melissa Pierce of her daughter. “She had questions, but I think the hardest part for her was that she started to discover herself, to discover black culture and black history … and her friends didn’t know where all of this was coming from.”

But the increasing comments from Pierce-Smith’s classmates only made her more determined to find out who she was. By the end of seventh grade, Pierce-Smith was certain about her racial identity; her accumulated research about her heritage provided her with a sense of understanding she realized she’d been missing.

As Pierce-Smith began to accept herself, her parents realized the lack of black culture she had experienced up until that point; they decided to transfer her to the Self Enhancement Incorporated Academy – a predominantly black middle school – for her eighth grade year.

At first, Pierce-Smith didn’t want to leave MLC because she had known most of her fellow students since kindergarten. She was going to have to make new friends in 8th grade and then again in high school.

Culture shock hit Pierce-Smith hard when she transferred to SEI; 95% of the student body was black.

“Once I got to SEI I had black people saying, ‘You’re such a white black girl,’” Pierce-Smith says. “It was hard because at MLC I had people telling me I was too black and then when I went to a predominately black school I had people telling me I was too white.”

However, as the year went on, the students at SEI began to accept Pierce-Smith. Birthday party invites were soon arriving at Pierce-Smith’s door, and she was making connections with friends during lunch.

It was at this time when Pierce-Smith started talking to her cousin – a cop in the Portland Police Department in Maine. But when Pierce-Smith began to express interest, her cousin tried to redirect her.

“He actually suggested I do something else because he says policing is a hard job,” says Pierce-Smith. “I told him I can handle hard jobs.”

With a big heart and determination, it was now Pierce-Smith’s dream to get involved and connect with others.

For Pierce-Smith, the duty of a police officer is to serve the community, regardless of the backgrounds or experiences people have. “You’re out in the community talking to people. They might not always be a threat,” says Pierce-Smith. “Police officers can make a kids day by handing them a sticker and that’s what I’m inspired by.”

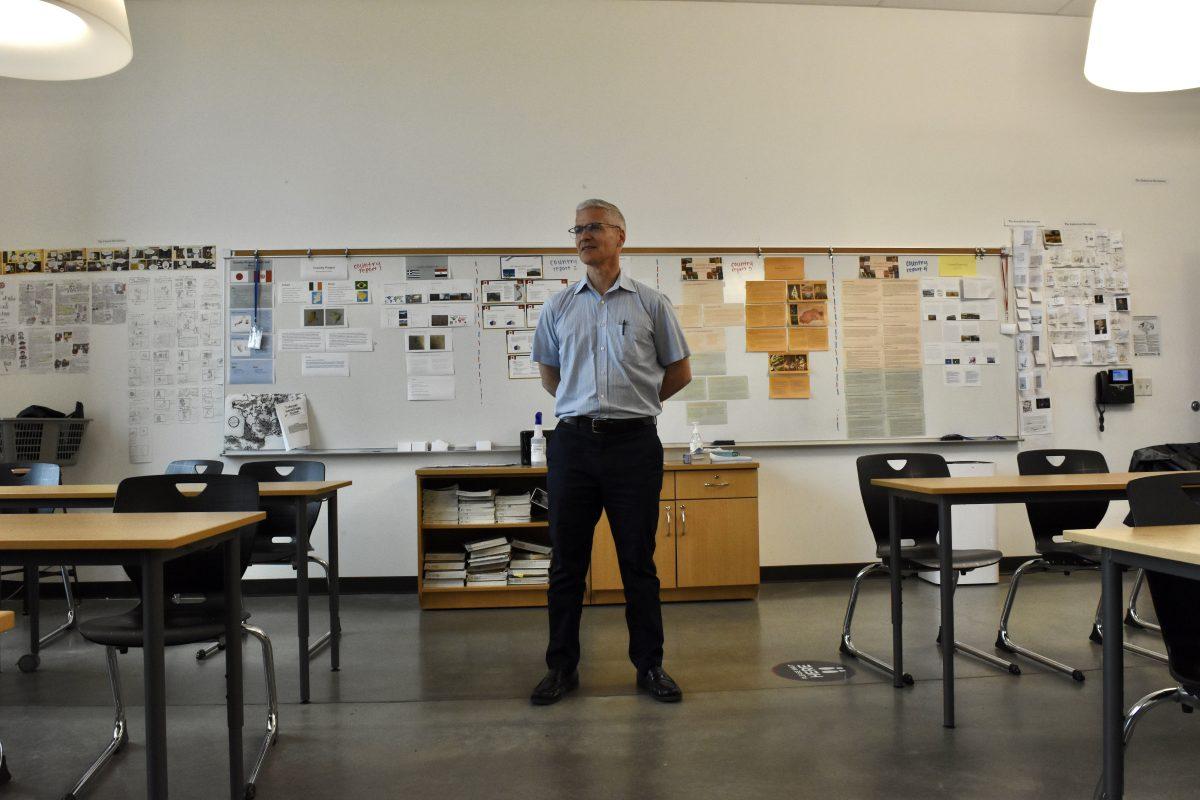

It wasn’t until her freshman year at Grant, when Pierce-Smith joined the Portland Police Cadet Program through Officer Williams, that her dream came one step closer to coming true. The program is designed to offer an introduction to law enforcement for those interested in becoming police officers. When Pierce-Smith heard about the program, she instantly wanted to be involved.

For Pierce-Smith, starting the program was like walking through a door into a whole new world; she spent hours each week learning how to handle dangerous situations, learning how to shoot a gun and participating in ride-alongs with officers. The program provided Pierce-Smith with a new perspective on the inner-workings of law enforcement.

“I just wanted to learn about anything they would teach me,” says Pierce-Smith.

But the longer Pierce-Smith participated in the program, the more she noticed how black Americans view police officers.

“There were some people of color who thought it was good that I was trying to make a difference,” says Pierce-Smith. “But there were others who would call me a traitor and think it terrible to associate myself as a young black girl with the police department.”

Yet, no matter what the environment looks like, Pierce-Smith believes it is important to take on the responsibility of helping others and doing the best she can for her community.

“Black people are so nervous around police officers considering all the brutality and profiling that happens,” says Pierce-Smith. “Putting a good face on police officers is important, especially for the black community.”

She’s not alone in this belief. Portland State University Sergeant Willie Halliburton recognizes the importance of connecting with citizens in order to establish trust.

“Getting involved in the communities as an officer and getting to know the people in the areas that you patrol will slowly give the ability to trust back to those communities that have been victimized,” says Sgt. Halliburton.

The opportunity to connect with her community presented itself to Pierce-Smith once again in her sophomore year, this time in the form of the Miss Black USA Talented Teen pageant.

Despite the fact that the pageant was like nothing Pierce-Smith had ever done before, she chose to participate with confidence and humility.

“I entered the pageant because I wanted to try something new,” says Pierce-Smith.

“I was surprised when Skylar said she wanted to participate in the pageant,” says Melissa Pierce. “It takes a while for Skylar to be comfortable with others, and we had never done a pageant before.”

The pageant consisted of a talent portion, a speaking section and a stage presence in both a dress and athletic-wear.

The morning of Pierce-Smith’s first competition was not any different from other mornings, and yet Pierce-Smith couldn’t help but feel anxious. “I was nervous to go on stage and perform my talent and answer questions on stage but my biggest fear was that I might trip and fall in my evening gown.”

Pierce-Smith’s heart skipped a beat as she walked on stage, smiling and waving at the audience in her long dark-blue dress.

Suddenly, the words of the announcer rang in Pierce-Smith’s ears: the 2016 Miss Black Oregon Talented Teen had been announced.

“I was like, ‘Woah I actually won.’ My mom’s crying and she never cries,” says Pierce-Smith. “All of a sudden it was very real for me.”

A tiara was placed on Pierce-Smith’s head as the audience erupted.

Pierce-Smith realized from that point on that she had become a role model for the Portland black community, like the role models she had once found in her favorite Disney princesses.

“I was suddenly recognized on the street and young black girls would start coming up to me and telling me they wanted to be like me,” says Pierce-Smith. This experience has helped her realize that everyone has hardships, but overcoming them makes you stronger.

Pierce-Smith now found herself balancing school, dance, cheerleading, her Miss Black Oregon duties as well as the commitment she made to helping protect and support her community through the Portland Cadet Program.

In April 2017, Pierce-Smith traveled to Washington D.C. for the pageant’s national competition. She would be competing against 10 other girls for the title of Miss Black USA Talented Teen.

“Every girl at the pageant was darker than me. But no one made a comment whatsoever, which I was really afraid of,” says Pierce-Smith. “But that wasn’t (what it was about) at all. It was like, if you have black in you let’s see how you can be proud of that.”

During the speaking portion of the pageant, Pierce-Smith was asked: “If you could have a few minutes on national television to promote something, what would it be?”

For Pierce-Smith, bullying was the obvious choice. “My platform was all about bullying,” says Pierce-Smith. “I feel bad that others have had to go through what I have been through, and I want people to be comfortable in the skin that they’re in.”

Although she did not win nationals, Pierce-Smith took home the 5th place trophy, a $1,500 scholarship for community service, the People’s Choice Award and a determination to commit to bullying prevention in her community.

Since then, she has focused on cyberbullying and has helped with Grant High School during “Speak Out Week” to fight the silence that victims of bullying deal with on a regular basis.

Serving as Miss Black Oregon for two years and enrolling in the Portland Police Cadet Program, Pierce-Smith has found her spot: being a role model who shatters social constructs.

Not many women are police officers. Not many women of color are officers. And there are very few who may even be a pageant queen. Pierce-Smith knows that she has a duty to show young black girls what they can do with who they are.

“After all the ups and downs of not being able to figure out who I was, having a little girl come up to me and say they look up to me was such a blessing because that little girl doesn’t know what I’ve been through,” says Pierce-Smith. “She just sees me in the moment for who I am.”

In June 2017, Pierce-Smith passed a written test and a handcuff test, allowing her to graduate from the Portland Police Cadet Program. But just because she is not putting on the uniform anymore doesn’t mean she is not making use of everything she has learned.

Pierce-Smith has taken the responsibility of speaking up for those that don’t have a voice and continues to educate others with her perspective from law enforcement.

One might see Pierce-Smith with pom-poms and a big bow in her hair on the sidelines of a Grant High School football game. Or one may see Pierce-Smith during a Portland parade, dressed up in a full length gown with a crown on her head, waving.

In the near future, Pierce-Smith may be found patrolling the neighborhood or on security patrol at city wide events as a full time police officer.

“Being a police officer lets me help those in times when they feel at their lowest,” says Pierce-Smith. “I have felt that way and I don’t want anyone to have to go through that.”

Pierce-Smith has found that she doesn’t have to choose between races or hobbies. Instead she will continue to believe in herself and build upon her experiences.

“Being in the cadet program and being crowned Miss Black Oregon were both character building events for me,” says Pierce-Smith. “I just want to make a difference.”