Into the Light

[aesop_parallax img=”https://grantmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/rape-culture-banner-1.png” parallaxbg=”on” captionposition=”bottom-left” lightbox=”off” floater=”on” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”none”]

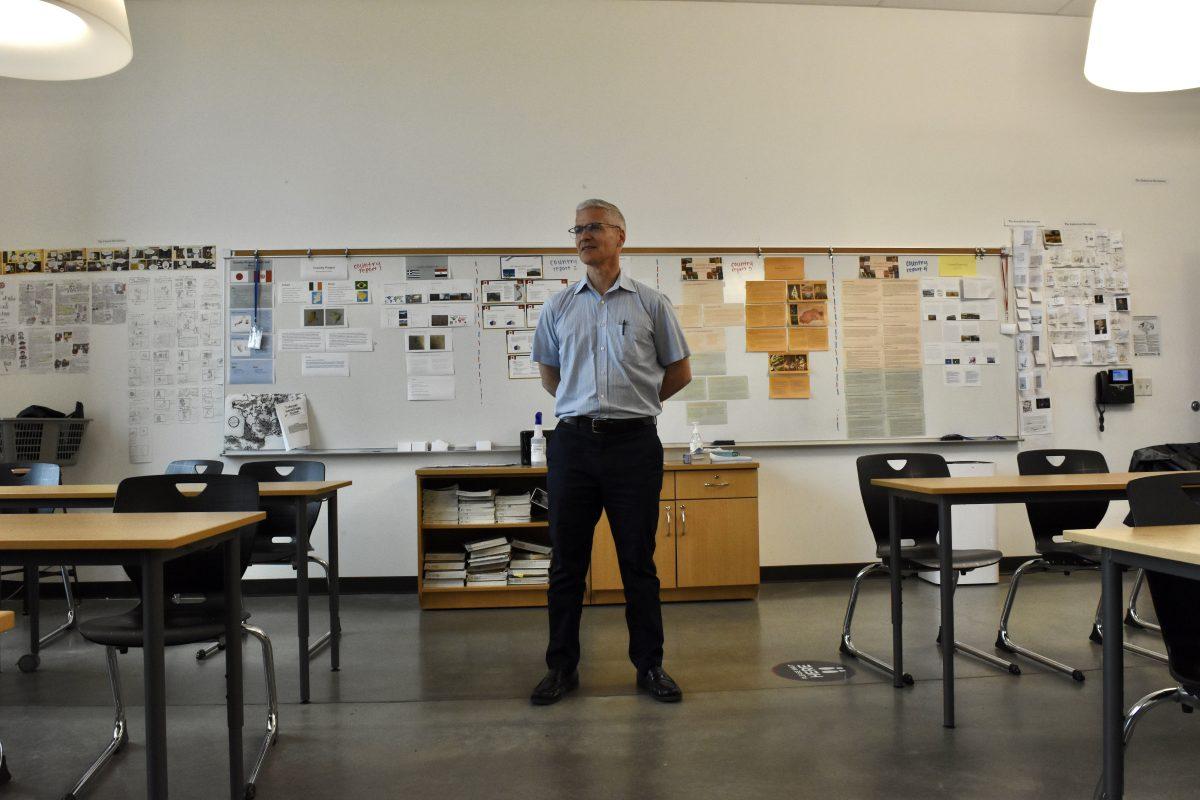

In early May, Grant was hit with an onslaught of debate on the topic of rape culture when Grant history teacher David Lickey wrote a letter questioning its existence. Rape culture is a term used to describe an environment whose prevailing social attitudes normalize sexual assault.

One excerpt of the letter stated that “Rape culture is a theoretical construct that is ill defined.” Another stated that the wording of the term is “hysterical.”

The letter was distributed to a class of freshmen and then discussed as part of a class unit on gender. By the end of the week, it had gained traction on Facebook and quickly ignited a response from the Grant community.

On the Monday following the incident, students wore red to show their solidarity towards sexual assault victims. Teachers brought signs to school written with messages, such as: “You can’t teach the history of Western civilization but deny rape culture.” On social media, students, parents and people around the country engaged in heated discussions over the issue, many speaking out against Lickey’s claims.

“You can’t tell people that their personal experiences aren’t true; you can’t say that that’s not the way that I feel or that’s not how I’ve navigated the world,” says Sage Davis, a female sophomore at Grant who is a survivor of sexual assault. “Just because you haven’t experienced something doesn’t mean it’s non-existent.”

Others thought that the letter’s backlash was unwarranted.

“I think when (students) took the whole thing and said, ‘This is all worthless because it questions an idea we have,’ I think that was sort of unproductive,” says Liam Purkey, a male senior at Grant. “While I think rape culture is prevalent and exists, there are a lot of Americans who don’t. I think skepticism about the extent to which it exists is something that is important.”

Amidst the debate, one thread remains unarguably true: Sexual assault is happening at an alarming rate for high school students.

Research conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that approximately 1 in 6 boys, 1 in 4 girls and roughly 1 in 2 transgender youth are sexually abused before the age of 18. And 98 percent of sexual assaults are committed by men.

But what is often overlooked is the ways in which social norms can lead to those alarming statistics. Rape jokes, catcalling, unsolicited nude photos, groping and a slew of other behaviors and attitudes create what many call a rape culture.

Jessica Murray, Grant’s activities director and leader of Grant’s Women’s Empowerment Group, says rape culture is a systemic issue.

“A lot of people fixate on the term ‘rape,’ and they focus on just that … And what they’re denying is the culture,” she says. “Rape culture is putting the responsibility for boundary violations on the person being violated … It’s as simple as walking down the hallway, and somebody says, ‘Smile!’ It’s a deep, layered system that has many levels.”

Sally McWilliams, the chair of the Women’s, Gender and Sexuality department at Portland State University, says the term is easily misunderstood.

“I think to a certain extent, the term ‘rape culture’ can be read as inflammatory,” she says. “Of course we don’t believe that there should be rape in our culture. And then we don’t want to lose track of the actual violence that is impacting young women and other young people’s lives.”

Many female Grant students say that rape culture follows them through the halls, at school dances and even in the classroom.

“During class discussions, it’s predominantly males speaking,” says Rié Durnil, a junior at Grant. “Sometimes (males) shut down females when they are having discussions. The idea that females’ opinions aren’t as valid and they aren’t as strong plays into rape culture.”

Grant freshman Sydney Rawls, who is a survivor of sexual assault, agrees. She points to being “catcalled” on her way to school and being groped in the halls as a precursor to more serious sexual abuse that many girls experience.

“When you really think about it, it is a form of sexual assault,” Rawls says of unwanted groping. “Even little things like that, they just pass it off, like ‘Oh, it’s fine, it’s normal,’ but if you really look at what sexual assault and rape culture is, that’s part of it.”

Dylan Leeman, a male English teacher at Grant who teaches the freshman class that initially received Lickey’s letter, says that he was unaware of the extent that female students experienced rape culture at Grant. When the question, “How does rape culture show up at Grant?” was presented in a class discussion, nearly every one of his female students had multiple experiences to share.

“I didn’t know that so many of my female students say that they hear rape jokes at school everyday,” says Leeman. “Teaching this unit for years, I didn’t suspect that that was the case here at Grant.”

Moving ahead, he believes other students and staff need to take the time to listen to the experiences of female students at the school.

“What we need to do now is dig a little deeper, listen more and find out what’s really going on and talk about how to improve the culture of consent and how to foster a culture of respect,” he says.

Murray believes minimizing rape culture at Grant is dependent on everyone’s own self evaluation.

“I think that what I’ve borrowed from the past, is that when we look at rape culture and we admit that it’s real, we then have to look at it and identify how we’re a part of it,” she says. “There are so many things that are part of rape culture all the way down … It’s these small things, these systemic structures.” ◆

Perspectives

Grant Magazine interviewed a variety of students who are impacted by rape culture. Here are their stories.

_____

[aesop_image imgwidth=”70%” img=”https://grantmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DSC_0505.jpg” align=”left” lightbox=”off” captionposition=”center” revealfx=”off”]

Eleni Mallos

Senior

“Dress codes are a huge part of rape culture. I’ve been dress-coded at Grant before. I was in my cheer uniform, and this was probably the most embarrassing and the most horrific experience I’ve ever experienced from a teacher … I went to go sit in the back with my headphones and go over choreography, because I had to teach later that day in the dance class. I was just closing my eyes and going through counts in my head, and the teacher got mad at me, and she was like, ‘Um can you go in the hallway? You’re distracting the young boys in here’ … I was shocked, and I just went in the hallway. But later I went in the classroom, and I was like, ‘Why couldn’t you just say you were distracting, period? Why did you have to say the part about the young boys?’ And she said, ‘Well you’re wearing that flashy outfit, and it’s just very distracting for the boys in here.’ It was super disappointing to come from a teacher especially … Like, how uncomfortable and embarrassing for me? … That’s part of rape culture, is that if a girl wears a flashy outfit, then a boy can’t control himself, and that’s just not OK. You shouldn’t be teaching that to such young boys.”

– Interview by Toli Tate | Photo by Finn Hawley-Blue

_____

[aesop_image imgwidth=”70%” img=”https://grantmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DSC_0364-copy.jpg” align=”right” lightbox=”off” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off”]

Sage Davis

Sophomore

“A total violation of space and violation of my sexuality and body is just everywhere I go. So whether it’s at school dances and having guys come up behind me and grab me and start dancing with me non-consensually. And I live just across the street from Grant and will literally get catcalls in that small window when I’m crossing the street and walking through the park – I get catcalled by students … The way I get looked at, it’s as if I’m not even a human being.

It’s as if I’m just a sum of my body. It makes me feel kind of like a piece of meat rather than a human being, as if my existence is something that should always be commented on and as if people’s opinions of my body are important. It just makes me feel like an object, and when you objectify people and when you boil them down to their bodies and lose sight of them being people, then I think it becomes therefore more easy to violate them.”

– Interview by Toli Tate | Photo by Finn Hawley-Blue

_____

[aesop_image imgwidth=”35%” img=”https://grantmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DSC_0588-1.jpg” align=”left” lightbox=”off” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off”]

Rié Durnil

Junior

“(At school dances) there is a lot of grinding. I don’t see a lot of consent, which is a huge issue … I know a lot of people, no matter what their reason is – it’s not okay, and they don’t want to have someone come up behind them … Freshman year at homecoming, I was really surprised by all that going on. I just remember wondering why people weren’t asking for permission. I saw people looking uncomfortable … For me it would start to get uncomfortable with guys moving their hands and not asking for consent.

At Winter Formal this year … I just remember, I really didn’t want him to touch me like that. I just walked away. But afterwards, reflecting on it, I was like, ‘What if something had happened?’ And I don’t know if I would have been able to walk away at that point.”

– Interview by Sophie Hauth | Photo by Finn Hawley-Blue

_____

[aesop_image imgwidth=”70%” img=”https://grantmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DSC_0523.jpg” align=”right” lightbox=”off” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off”]

Anonymous

“I had a crush on this guy, and he liked me back, so we dated … We were best friends, and then in seventh grade, things got weird between us, and he kind of pressured me into having my first kiss. And it just escalated from there, until I would feel like I had to go over to his house and make out with him. And I never really liked it. And eighth grade, it got really bad, and he made me feel absolutely awful about myself, like I didn’t eat, and I hated every aspect of myself, and I couldn’t study in school … He told a lot of the girls that I forced him to make out with me and like jumped on him, and they all hated me. And they would call me a whore … I would have to go over to his house. Every time I was there, I’d be very uncomfortable, and he’d pressure me into doing stuff that I really did not want to do. He’d threaten me if I didn’t go. Now, coming to Grant, I’ve gotten new friends. They help me and they help me get out of it mostly, but I still am afraid of him … I can’t really explain it, I’m just terrified of him. He’s like the only thing I think about, and I can’t walk down the hall because every time I see his face, I shudder … I think it’s going to be fixed, but I just have to wonder, how do people who have been raped feel? Like I haven’t been raped, I was pressured to make out with someone, and I’m terrified of him.”

– Interview by Sophie Hauth | Photo by Finn Hawley-Blue

_____

[aesop_image imgwidth=”35%” img=”https://grantmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DSC_0419-copy-1.jpg” align=”left” lightbox=”off” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off”]

Sydney Rawls

Freshman

“Early in my eighth grade year, people started talking and saying more things. If people were wearing more scandalous clothes, guys would say more things and kind of give hints that were kind of weird in many ways. I didn’t really think anything of it, until I would like talk to my mom and stuff, and she would be like, ‘Well, that’s not really appropriate, that’s like a form of this thing.’ And then, starting my freshman year, I heard more about things like that. There’s been instances where I and my friends have had people grab their butts or something, and they like didn’t know who it was. It was just a small thing, we kind of really passed it off as a small thing. Until I did real research on it, I was like, ‘This is really what rape culture and sexual assault is.’”

– Interview by Sophie Hauth | Photo by Finn Hawley-Blue

_____

[aesop_image imgwidth=”70%” img=”https://grantmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/DSC_0655.jpg” align=”right” lightbox=”off” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off”]

J.D.

Junior

“We were at his house, and he just would not take ‘No’ for an answer … I had told him ‘No,’ and he was very demanding and manipulative mentally, just saying, “You just don’t care about me,’ like, ‘Come on just do it,’ and super aggressive. It was just sex to him. And I kept saying ‘No,’ and he just kept going, ‘Come on’ … It was a physical struggle. I just hit a point where I was like, there is just nothing I can do. Because he is aggressive, and if I try to do anything, he will just be more aggressive. I just gave up and was like, ‘There is nothing I can do’ … That was my rock bottom, and I am never, ever going to go anywhere near that for the rest of my life … There are people that are capable of terrible things. Especially throughout high school and middle school, I came to the realization that rape culture exists, and not everybody around me is going to be respectful of women’s bodies or my body. That there are people at our school and outside of our school that don’t care and don’t have that respect, that have the capability to assault someone, to manipulate someone, to force someone to have sex with them, that don’t understand what it’s like to be a woman and be treated that way … The more I have a better understanding of the predicament I’m in and the climate of rape culture at Grant, the more powerful I am. The more aware I am, and the more I know how to respond and how to deal with it.”

– Interview by Georgia Greenblum | Photo by Blu Midyett

_____