The sharp ringing of the alarm on her bedside table awakens Kiara Brunner, a former junior at Grant who uses the alias “Bhaddie” on social media. Brunner shuts off the alarm and reaches for her phone, eager to respond to the 300 messages and 60 pictures she received through Snapchat — a social media platform — while sleeping. Checking her clock, Brunner calculates how much time she can spend on her phone before getting ready for the school day.

After spending 15 minutes scrolling through Snapchat messages and sending texts to her friends, Brunner takes a shower, gets dressed and stands beside the stove – snapping pictures of herself while cooking breakfast – to respond to unread messages from the night before.

Brunner gained her large following on social media by posting frequently for the entirety of Grant High School to see. Eating her breakfast, Brunner walks to her room and positions herself in front of her full length mirror, poised to capture the perfect image for her daily Snapchat story. Her eyes light up as notifications pop up on her Snapchat inbox screen. Fans flood her message board with overwhelmingly positive messages such as “thank you so much for responding,” and “you made my day,” in response to her replies.

Brunner may not have a real life relationship with the majority of the people she sends pictures to on a daily basis, but she values the influence that she has in the online community. Using her leverage on social media, Brunner helps people who are struggling.

“On average 2,000 to 3,000 people a day (view my posts),” says Brunner. “Sometimes more. Sometimes less. Like right now I have like 72 Snapchats and 469 messages. I like social media because I can reach a large number of people in a short time, and it is just easier to talk to people that way.”

Like Brunner, the majority of teenagers who use social media find that it brings them a sense of happiness. Teens value the constant connection with their friends and peers and the momentary confidence boost that a positive comment provides.

Many students at Grant who struggle with mental illness have also found social media as an outlet for support from their peers.

“If someone has a similar situation and they have been going through the same stuff as me, they could help me,” says Brunner. “If I am having a bad day they will come (comment) on my story and ask me if I’m okay and ask me if there is anything they can do to help.”

But some teenagers are only conscious of the temporary benefits that social media provides.

Based on data from the Pew Research Center, 73 percent of 14 to 17-year-olds use social media daily. Social media consumes a large portion of the time that today’s youth have outside of school.

Grant junior Ella Kohn recognizes how distracting and addictive her phone can be. “I found (social media) taking up the majority of my time when I would be doing homework,” she says. “I would go on Instagram or Snapchat for a while and then I would realize, ‘Oh I still have two hours of homework to do and it is ten o’clock.’”

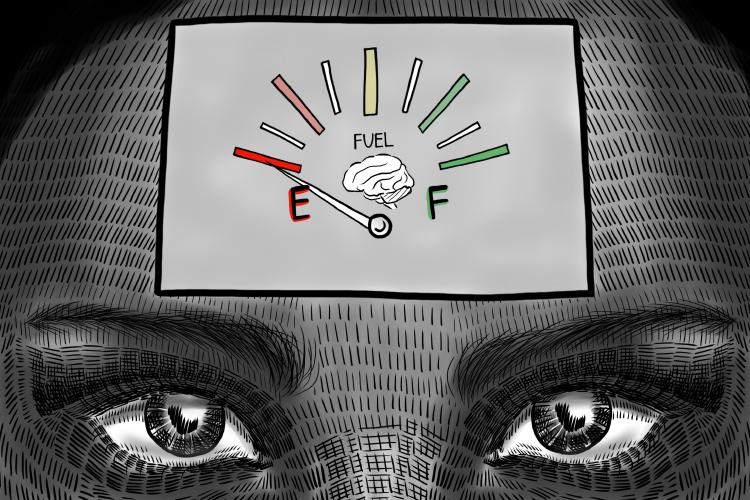

The excessive amount of time that teenagers spend online looking at posts from their peers leads to a feeling of social isolation. This results in higher rates of depression among students.

According to a study done by the Journal of Pediatrics, there has been a 37 percent increase from 2005-2014 in teenagers who reported a major depressive episode within the previous year. The study defines a major depressive episode as a period of time — which lasts for a minimum of two weeks — when someone experiences hopelessness and general discontent. They may also have a loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities and problems with sleep, energy and concentration.

The rapid increase in social media use nationwide, coupled with a rise in depression and anxiety rates among teenagers in recent years, has led to several hypotheses by behavioral scientists that the two are linked.

“The research that is coming out these days says that teenagers spend 40 percent less time with their peers face-to-face than they did fifteen years ago,” says Sean Marshall MD PhD, a licensed counselor and expert on teenagers and their relationships with technology. “I think that plays a big role in why teenagers these days are struggling more with depression and anxiety than generations before,” he says.

Grant history teacher Daniel Anderson agrees. He says that when social interactions happen over a screen, rather than face-to-face, there are fewer opportunities for today’s youth to learn how to communicate effectively.

“Everything (posted on social media) is so sanitized and choreographed so there’s no room for messy conversation,” Anderson says. “There’s something fundamentally different (about) eye contact and body language … There’s a spontaneity to this.”

Sophomore Eddie Peterson is one of the few Grant students who does not use social media. “I don’t use social media because I never really felt the need to,” he says. “If I wanted to have a friendship I would do it in person rather than over a screen.”

The inability to connect with others in person leaves teenagers with incurable feelings of isolation, social anxiety and, ultimately, unhappiness. This is why the responsibility that comes with social media must not be left entirely to the young and developing minds of teenagers.

Monitoring social media is largely seen as a responsibility of the adults in a teenager’s life. Crystal Ball, a Grant parent, says, “It’s a battle in my house. I think most of the time I try and have a cell-phone free zone. It works mostly, but sometimes I choose not to rock the boat so that we’re all happy.”

However, separating teenagers and their online communication is more difficult than it appears to be.

“A lot of parents struggle with (restricting social media) because they recognize that this is how (their children) connect, so putting more boundaries on it may negatively impact their teenager’s ability to maintain healthy social relationships,” Marshall says.

When social media use is left up to the discretion of teenagers, it can often result in an unhealthy relationship with online communication that can bleed into real world interactions. In Brunner’s case, she had been confronted at school by people who knew her as “Bhaddie” on social media, and attacked for her physical appearance and the people that she was friends with.

“There were just some petty and childish comments, like, ‘You’re ugly, you’re short.’ It’s for stuff that I can’t really control,” says Brunner. “Then people started attacking my friends and it was hard. Those people didn’t know anything about me and they’re talking about people who were there for me from day one.”

This harassment that stemmed from social media ultimately contributed to Brunner’s decision to transfer to Benson High School after her first semester at Grant.

For Brunner, like most teens, social media has been both a resource and an obstacle.

Marshall has seen this same trend and believes it will continue in the future. “More and more research is starting to show the negative impacts that are coming out of our technology and social media,” he says. “So does it make people happy? I think in some ways, but I think it’s also a bit of a perceived happiness as well.”

Daniel Anderson, history teacher

“Sometimes I feel like my phone controls me, and I feel like that’s even more so with teenagers. If there’s ever a down moment in class, they look at their phones rather than having authentic conversations and interactions with other human beings. Your phone is nothing but hours and hours of shallow nothingness and you’re supposed to be a deep, reflective and a thought-provoking person with a deep soul.”

“I think everybody wants to feel important, everybody wants to feel valuable, everybody wants to feel like they matter in this world and (social media is) an easy way to do it. It seems to make people feel isolated if their posts are not responded to and there is pressure to feel like, ‘What’s wrong with me if my posts don’t get lots of likes or shares?’ Everybody else’s life looks amazing on social media and (teenagers) tend to compare themselves to that.”

Mira Kulkarni, Junior

“(Teenagers) have a harder time having face-to-face conversations because it’s so easy to say stuff over the internet and not get the consequences that you would face-to-face. I think that a lot of the stuff that can be posted on social media can have a negative effect on some people. A lot of teens nowadays are a lot more sensitive. There are a lot of things that are posted that can be super offensive to some people and not really funny. I think that now I’ve made myself strong enough that I don’t really take to heart what is said on social (media). Of course when I was in middle school and stuff that was a bigger issue for me. I would post something and people would call me a ‘hoe’ … and it would affect me more … At home, I wouldn’t really want to talk to anyone on social media after school.”

Darius Guinn, Senior

“It’s kind of cool in the moment to see how many likes you can get, but it’s not really that important. I mean, there is way more to life then how many likes you can get on a picture. I never really get happy over it. It’s not like it brings joy – it’s just like, ‘Dang that’s crazy, I didn’t know that that many people really cared that much to like a picture of mine.’”

“It’s kinda hard with the amount of followers that I have because it’s like everywhere that I go there could be eyes on me. In no way, shape or form am I a celebrity but it’s just like, to a certain extent, it’s like if I post something that another normal kid would post that didn’t have as many followers, and let’s say it had something in it that it wasn’t supposed to, it would be easier to get screenshotted or … get sent to more people to the point where I get in trouble. You have to hold yourself accountable more on a day-to-day basis.”

Kiara Brunner, Junior

“If I can make someone else smile, that makes me feel better because if that person was having a bad day and then just them watching my story or looking at something on my social media made them smile or laugh then that makes me feel good. I think I try to put out as much positive content as possible. I know I get hate for it and I know that people don’t like me, but at the end of the day I would rather focus on all the people who do love me and who do appreciate what I do.”

“When I do come across a person who is maybe sad or depressed I try to help them through it … and see what the root of the problem is. If someone has a similar situation and they have been going through the same stuff as me, they could help me.”

“I didn’t have any friends starting at Grant. When I walked in those doors I knew zero people. Now, today, I know probably most of the school.”

Eddie Peterson, Sophomore

“My friends really want me to (join social media) but it’s just never been something that I have been super interested in doing and I have seen people change in their behaviors as they join social media … This guy (I was friends with) used to be really friendly and nice to people and then he just started becoming more self-centered and centered around his phone and it would be a lot harder to find time to hangout with him. It felt like he was choosing social media over me which was frustrating since we had been friends for like five years and then that just ended.”

“(Social media) makes people more attached to their phones rather than real world relationships and it makes people less comfortable in situations where you have to interact with others face-to-face … A lot of teens rely on their phones to maintain their relationships. I think some people are (aware) and they don’t care but some people just don’t realize it.”