As sophomore Ny’Asia Harris sits in the dark of her shuttered classroom at Grant High School in September, her classmates crowd around their teacher’s desk during a lockdown drill. The 15-year-old can’t help but think back to the day last school year when she was a student at Reynolds High School.

A boy brought an assault rifle into Reynolds, shot another student to death and then turned the gun on himself.

“It felt like a flashback of what happened before because it was quite long,” Harris says of the drill. Thoughts raced through her head: “Is this real? Is this going to happen again?”

In another classroom at Grant, sophomore Maddy Piazza, 15, watches as boys in her class play the mini-football game “tec-tec” and girls chat nonchalantly. “No one was taking it seriously,” Piazza says.

Lockdowns at the school and across the district are happening more frequently after the Reynolds shooting. District rules call for classrooms to have lights turned off, doors locked and for students to move away from the entryways until administrators give the all-clear signal.

But so far this school year, the drills at Grant have proven to be chaotic, at the least. At best, they show the school is a ways away from making sure students and staff are well versed at being safe if something catastrophic happens.

Consider what happened during the school’s first few drills this year:

• At least two classrooms didn’t get a notification of a lockdown drill occurring because of phone troubles.

• Some teachers continued to teach during the events, despite rules saying lights must be turned off and everyone must be quiet.

• A number of teachers say they weren’t told when the drills ended and stayed in their darkened classrooms with students long after they were over.

• Some teachers didn’t know what to do and consulted their students for help, while other teachers allowed students to move about the classroom.

A planned fire drill in early October didn’t go much better, with students flooding onto the field in a giant swirling mass rather than the ordered lines they were supposed to be in. Several classrooms became separated from teachers.

Though a second lockdown drill at the beginning of this month showed some improvement, there were still trouble spots.

Science teacher Kelly Allen put it simply: “The communication in our school is lacking.”

With more than 16 new staff members at the school this year, some say the absence of training and the lack of communication are causes of the mishaps. Others believe it is an issue of culture and a mentality of not taking drills seriously. Still others wonder what the best way is to prevent a dangerous situation and whether the current drills are harmful to fragile students.

“It sounds like the drills aren’t happening the way they’re supposed to happen, so that makes me a little nervous,” says Grant parent Brittany Andrus.

Administrators at the school are clear the drills are necessary to protect student safety. Says Grant Vice Principal Claudia Ramos-Tetz: “That’s why they’re called drills. It’s an opportunity for people to practice and be able to identify areas that need to be improved.”

Portland Public Schools emergency preparedness manager Molly Emmons says maintaining emergency safety “is still a work in progress.”

But many can’t ignore the implications of drills that come with organizational issues. In the past, district administrators focused on issues involving disputes among students. But in the last few decades, the profile of the rampage shooter has emerged.

The Reynolds shooting is one of the latest in a history of school shootings. In Oregon, the most notorious incident occurred in 1998 at Thurston High School when student Kip Kinkel went on a shooting spree after slaying his parents in their home. He killed two students at the school and wounded 37 people before being taken into custody.

At Reynolds, Harris remembers walking to her first-period class on the day of finals last June. Suddenly, she and other students were herded into a nearby classroom. “It was shocking,” she says today.

She and her classmates crouched in silence for hours, learning through social media pieces of what was happening: that someone had been shot, but they didn’t know who. After the incident, she decided to transfer to Grant.

Allen remembers about eight years ago when she was dumbfounded to see a gun fall out of one of her student’s pockets when he leaned over. Later, she discovered it wasn’t real. But the incident troubled her. “That was one of my scary moments as a teacher,” remembers Allen. “In my head, I was thinking they don’t train you with how to deal with this.”

At Reynolds, some luck and the faculty training, authorities say, saved lives. A teacher who first encountered the shooter and suffered a gunshot wound managed to call the office and get the school put into lockdown. Classes weren’t yet in session and two school police officers were already at the building and helped corner the shooter.

In 2010, PPS received a Readiness and Emergency Preparedness grant of more than $650,000, which allowed the district to re-examine and fine-tune safety practices. The grant expired in 2012, months before the school shooting in Sandy Hook, Conn., that took the lives of 20 elementary school children and six adults.

Afterward, Grant began to lock several doors around the building to decrease the number of access points a potential shooter might have, according to vice principal Kristyn Westphal.

Still, problems with security persisted. After the Reynolds shooting, a report came out detailing the lack of preparation and security in Portland schools. Grant, it was found, had only had one lockdown drill in the entire school year, which was an accidental one that came the day after the Reynolds shooting.

How other districts handle training varies. In Lincoln County, teachers are shown safety videos geared toward threats like school shootings. In Estacada, educators hold monthly lockdown drills.

This year, PPS administrators began a new centralized tracking system to help hold schools accountable for getting in their required number of drills. Change seemed on the horizon.

But, if the first few drills are any indication, several problem areas still need to be addressed, teachers and others say.

In the staff meeting at the beginning of the year, administrators were clear with teachers about the importance of drills. Teachers were referred to a red notebook tucked into their safety buckets they could use as reference.

But teachers say often, in the swirl of lesson planning, that reading got put on the back burner. French teacher Ann-Marie Reid estimates only about half of the teachers actually read through the safety manual.

Some teachers didn’t even have the district-provided safety buckets, a result of a low budget and difficulty projecting the number each school needs, according to Emmons.

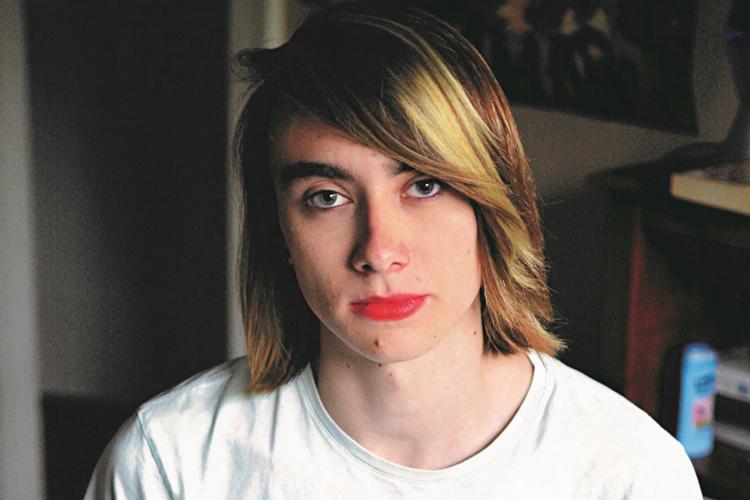

Language arts teacher M. Deych was one of those who didn’t get one. Having heard the lockdown procedure only briefly in a staff meeting, the new teacher tried to manage during the first drill. Deych pulled down the blinds and moved students away from the door, but allowed them to be on their phones.

“I know it was just a drill, but it’s still a little unnerving for the expectation to be really high and be really prepared, and to not supply me with what they want me to be prepared with,” says Deych.

Kianne Noakes, another new Grant teacher, also wasn’t provided a bucket. Like Deych, she had ideas about what to do, but was frustrated about not having a reference. She added that at other schools, she received actual hands-on training before the drills.

Not only that, but Noakes’ classroom, situated in a portable, wasn’t told when one of the first drills had ended. Her classroom was locked down for a total of 45 minutes, considerably more than almost all the other classes. For Noakes, anxiety and confusion mounted. For her students, restlessness ensued. Things like that make her wonder how the class will make up lost time.

Band teacher Brian McFadden didn’t get notified at either the early September drill or the most recent October accidental event that things were all clear. Students were stuck in the class and he lost valuable rehearsal time.

In the early September drill, at least two classrooms didn’t find out there was a drill because the phone system didn’t notify those teachers. The same thing happened to two other classrooms during the October accidental drill.

Rachel Peri, a Grant junior, remembers someone coming into her unlocked, active classroom and telling them that they were in a lockdown. At first, Peri was confused. How had they not known about the lockdown? Was it a drill or a real-life situation, some wondered.

In hindsight, though, the gravity of what had happened sunk in and replaced the confusion. “If we hadn’t gotten an alarm, and if something dangerous really was going on, the fact that we wouldn’t have been prepared is really frightening,” Peri says.

Some veteran teachers were unhappy with how both drills were conducted compared to past years.

During the first drill, math teacher Pardis Navi opened her door after the police had knocked two or three times. Security uses the knocking technique as part of acting like there is a real-life security threat in the building.

In the handbook, teachers are instructed to not open the door for anyone – administrators would have a master key in reality.

When Navi opened the door, she was told by a policeman “You’re dead” in front of her entire class.

“They tell us it’s for our ‘own good,’ but scaring us and stressing us when we’re completely powerless in a real situation…and then it’s like, ‘Oh, OK, nevermind now. Start teaching,’” she says.

She was also told that she should have had furniture blocking the entrance, something that was never communicated to her. A review of the safety handbook provided to teachers shows no instructions about furniture in front of the door, though it suggested moving students away from windows.

Communication with administration is one of the top complaints teachers have about safety and drills. “They could be a little bit more explicit with exactly what is expected of people,” says Deych.

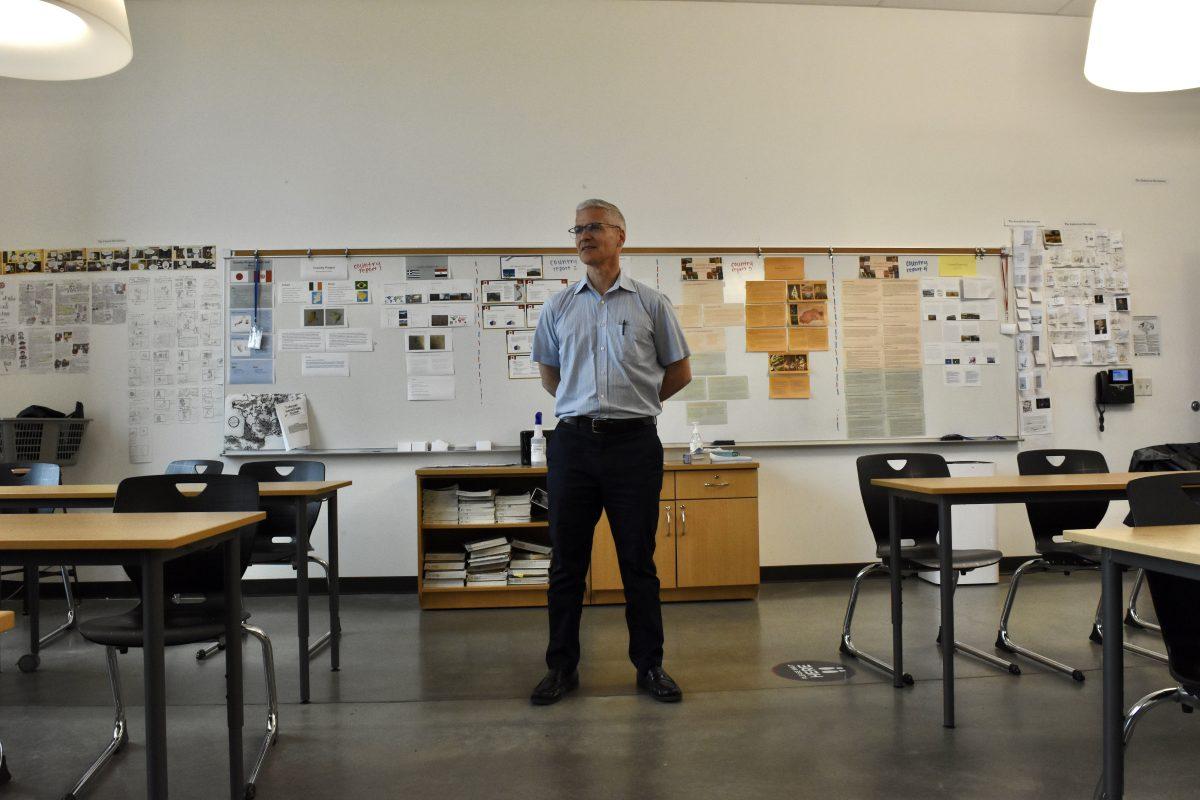

Some teachers have taken it into their own hands to combat against the loss of class time for drills. History teacher Jeremy Reinholt, along with at least one other teacher, continued teaching in a “stage whisper” throughout the second drill.

“The district is so desperate to cram in every minute of seat time that it can this year, I am sure that they wouldn’t disapprove of me using the time allotted to me during drills,” he says.

Navi wonders why Grant doesn’t use the phone system to communicate when drills are over to prevent the time loss. After all, she says: “We use the phone communication to communicate matters that may be trivial.”

In early October, a team response lockdown came right after a lockdown drill, causing massive confusion. A student was suffering from a medical issue and emergency personnel were called to the school. Administrators blocked off hallways and prevented students from leaving out of center hall doorways as the final bell of the day rang during the incident.

Again, several classrooms remained locked down and teachers didn’t know how to respond.

The frequency of the drills has some flustered. Many new teachers, according to veteran English teacher Russell Peterson, were hazy on the difference between a team response and a regular lockdown.

“The expectations of where students should go was not very clear,” Peterson says, adding that unclear instruction “while it’s frustrating, it’s understandable.”

Peterson also noted that in the day following, the administration made up for it by sending out an email to reset expectations and apologize for the confusion.

From the administration’s point of view, teachers have a long way to go executing drills successfully.

Students who have had drills in multiple classrooms report that a range of practices among teachers exists. “Some teachers will have no talking and will have, like, control of the class and then in those classes you sit in the dark and just don’t speak to anyone. But then in other classes there’s just people whispering,” says Peri.

In junior Claire Toland’s class, the teacher asked students for help on what to do, and continued class, albeit at a lower volume.

Officer De Shawn Williams, the Portland Police Bureau School Resource specialist, says the first lockdown drill made him feel “sick” and he described it as the “worst” lockdown he’s ever seen.

During the drills, he walked through the halls knocking on doors to try to see if teachers would open them. He says as many as 10 doors were opened for him.

In some classes, it was students who came to the door. In others, adults were still teaching. And each of those classes of around 30, he says, would be vulnerable if a real school shooter was involved.“When you add up the potential loss of life, it’s mind-boggling,” he says.

Williams says it’s a problem of people not taking it seriously and having the mentality of: “It won’t happen here” among both students and staff. After the first drill, he was disturbed to hear that one teacher thought the drill was a joke.

That sentiment is playing out in other areas regarding student safety. As students flooded out school doors for the first fire drill of the year, it was a picture of confusion. Students disbanded from classrooms and joined friends to talk in small circles. Almost no one lined up on their designated yard lines on the football field in the Grant Bowl.

Senior Libby Friedman became separated from her class. “My teacher never went over where to go. Half my class was scattered,” she says of the drill.

During the lockdowns, it appeared more kids were focused on their cellphones than on the drill at hand. Says Toland of the first drill: “No one seemed as worried as I was. My friend was sitting next me, and she was kind of like, ‘Why is this not a bigger deal?’ And I mean drills have always been sort of a joke in school.”

Harris says students should wake up and not be apathetic. She bases that on her experience at Reynolds. “I’m going to take lockdowns more seriously than I did in the past,” she says.

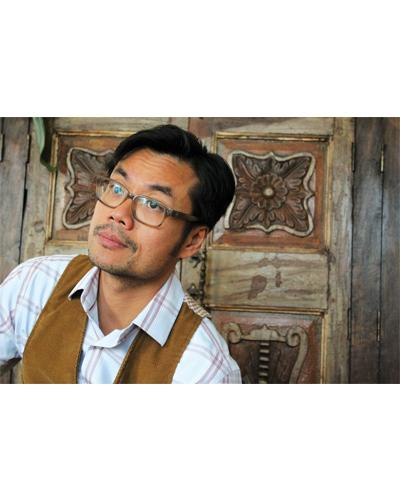

Her U.S. history teacher Shardon Lewis is famous for the dramatic safety talks he gives on the first day of school. He takes every drill seriously to prepare “for the unthinkable,” Lewis says, who has experienced real lockdowns for nearby violent acts before.

Lewis’ classroom was silent. When a security person came by to unlock the door, they were surprised to see students inside because it was so quiet. “Which is exactly the way it should be,” Lewis says.

For Harris, this provided comfort. “It was better in a way to know that he takes safety top notch,” she says.

Andrus, who has two children attending Grant, thinks the school should take security more seriously. She says when she has volunteered in the past, she sometimes forgot to sign in at the main office. No one would ask her any questions, something that concerned her, given that she could be anyone without a visitor badge.

On the other hand, she doesn’t want her kids losing class time to drills. Instead, she believes Grant should balance safety with instructional time. “Developing an effective system for doing a lockdown drill shouldn’t be so difficult,” she says.

Navi says she wants school officials to think more about prevention rather than overreaction. “The mentality of school districts is a police mentality,” she says. “‘How are we going to react when this happens?’ What I have not seen is: ‘What are we going to do to identify students who have mental health issues?’”

History teacher Don Gavitte agrees. “We certainly have to have honest conversations about, ‘OK, why exactly are we preparing so intensely for the possibility of a shooter in the building?’ That’s because there’s plenty examples of this happening,” he says. “We need to have honest conversations about preventing this kind of action.”

When asked about training for spotting problem kids, Principal Carol Campbell said staff get help so they can spot child and sex abuse, but there’s not much training around dealing with kids who have mental health issues.

The district, she says, has a specialized team that comes in for counseling, but only once the event has happened.

Ramos-Tetz says the school is taking the necessary steps to establish safety protocols. “We are trying to establish a school culture that really takes it seriously,” she says.

Grant has been on the cutting edge of a variety of informative events, including hosting a bullying summit and giving hard-hitting presentations on the dangers of drunk driving. But so far there hasn’t been anything, according to Campbell, drafted specifically for school safety procedures.

Andrus suggests having a state trooper come to the school to talk to students, something that happened at her workplace. They put a poster in her office, a constant reminder, of what to do in case there is an active shooter in the building, and she says it made an impact.

“How is it we have the resources in my office filled with middle-aged people but we don’t have the resources to do it in schools?” she asks.

Williams says teachers should be on the lookout for at-risk students. He, too, was once on track to be a teacher, and he could tell the difference between those who were “engaged” and those who just wrote lesson plans and stood at the front of the room to talk.

“It’s just really important that we all take it seriously and it’s not only from the adults, but it’s from everybody,” says Ramos-Tetz.

With Grant’s remodel on the horizon in three years, according to Emmons, the school will become much more structurally equipped for safety. There are plans for using the doctrine of “crime prevention through environmental design.”

Locked doors and cameras at the front of the school are just two of the projected additions.

Says Andrus: “My fear is that they will, you know, go, ‘Oh we’re getting a new school soon,’ and that they will do absolutely nothing” in the meantime.

For now, says Campbell, “What you want ideally is an ongoing training and education that can help sustain that culture of responsibility with everyone who’s here.”