The John Marshall High School campus is tucked into a secluded pocket in Southeast Portland – a three-minute walk from Eastport Plaza on 91st Avenue and Powell Boulevard – and spans more than 23 acres. The now-shuttered high school sits just east of I-205 in the heart of the Lents neighborhood.

The school is empty, closed in June 2011 because Portland Public Schools officials say its enrollment was declining and the district wanted to consolidate high schools. Today, it’s mainly used as a testing site or for athletic events.

In November 2012, voters passed a School Building Improvement Bond that grants PPS an eight-year, $462 million budget to reconstruct Franklin, Roosevelt and Grant high schools, as well as Faubion Middle School. Seismic and other safety upgrades will also be made at 63 other schools.

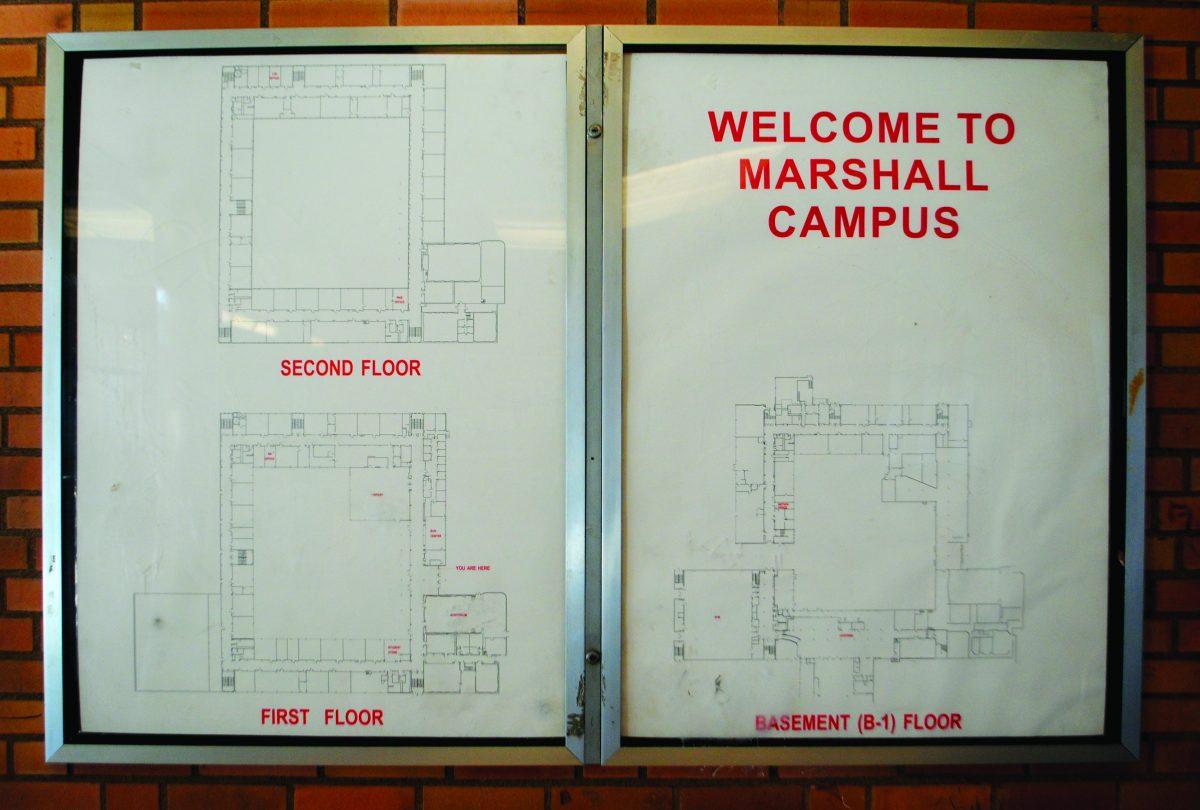

Next fall, Franklin’s teachers and students will relocate to Marshall for two years while the school is renovated. Grant will follow in September 2017 when the Marshall grounds will become “Grant High School at the Marshall Campus.”

But an examination by Grant Magazine has raised serious questions about the upcoming move of Grant students, teachers and staff to Marshall. Interviews and public records show the decision conflicts with the commitment to equity that PPS administrators say underpins everything the district does; that the decision was made without engagement with the full Grant community; and the option of moving to Jefferson High School, which is far closer than Marshall, was barely considered.

In June 2011, the school board passed an aggressive policy, known as the Racial Educational Equity Policy, designed to promote racial equity. The district has faced serious concerns regarding the matter in past years and promoted the policy with the intention of taking things in a new direction.

It reads, in part: “Portland Public Schools’ historic, persistent achievement gap between White students and students of color is unacceptable. Portland Public Schools will significantly change its practices in order to achieve and maintain racial equity in education. Educational equity means raising the achievement of all students while (1) narrowing the gaps between the lowest and highest performing students and (2) eliminating the racial predictability and disproportionality of which student groups occupy the highest and lowest achievement categories.”

Equity has been an issue at PPS for years. According to district reports, the graduation rates have been narrowed between white and Hispanic students, but there still remains a 10-point gap. African Americans’ graduation rates have stayed at just 53 percent over the last four years and black students are nearly five times more likely to be expelled than white students at high schools in the district.

The district has spent millions of dollars in attempts to close the achievement gap, investing in employee training through Courageous Conversations – a program designed to get adults in the district talking about how students of color are faring. Last year, district officials put close to $1 million into its Office of Equity and Partnerships.

Yet, shipping the Grant student body to Marshall runs contrary to what the equity policy is supposed to promote. The burden of the move will fall most heavily on those students the equity policy purports to help. Put simply, those who are most vulnerable will be at the biggest disadvantage in terms of getting to school, with many families that are low income or that have students of color having to make a trek roughly 10 miles from where many of them live.

And it appears the move came with a lack of community collaboration in a district that prides itself on involvement from the community.

For Rachell Hall, a parent of a Grant freshman who is black and lives near North Gantenbein Avenue and Shaver Street, the lack of community input is frustrating. She says it wasn’t until her son’s first week of school at Grant that she found out about the 2017 move.

“I wouldn’t have even sent him to Grant as a freshman knowing that he would have to cut out going to Grant to go to some other school,” she says. “That’s ridiculous. That’s too much transition. I wouldn’t do that to my son.”

Finally, the district barely made any efforts to consider Jefferson, which would’ve helped students of color have better access to school.

The Marshall campus is more than six miles away from Grant and it takes close to an hour to get there via TriMet from the front steps of the Northeast Portland school.

In fall of 2017, families all over Grant’s district will be left with a drastically different transportation situation. For students whose parents can afford paying, that means giving their kids the car or dropping them off at Marshall via 15-20 minute car rides, depending on traffic.

For others, however, the change will be backbreaking. The district provided a map from April 2014 based on students with historically underserved populations, such as special-education eligible students, students eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunches, students with limited English proficiency and students of color.

Many of those families live closer to North and inner Northeast Portland and are looking at a 9- to 10-mile commute every morning, roughly the same distance it would take to travel to Vancouver, Wash., from the Grant Park neighborhood. A TriMet trip to Marshall from that area would take well over an hour.

“In my particular kids’ case, it would pretty much be the death knell,” says Amanda Moore, a white parent of a current Grant senior and an eighth grader at Irvington School. She lives on North Williams Avenue just off North Lombard Street and says she is low income. “To tack on all this added responsibility of commute and time management…there’s no way. This would just blow it out of the water. This would be like, ‘Oh, forget it.’”

Her sons, who split their time between their parents, are eligible to go to Grant because their father lives near Northeast 15th Avenue and Prescott Street.

Don Gavitte, a veteran social studies teacher at Grant High School, recognizes that traveling to Marshall will be an especially tough transition for some students. “Our most vulnerable students are going to have the toughest time getting over there and that’s all there is to it,” he says. “So we need to make accommodations that fit for everybody.”

Without efficient and inexpensive transportation options, Gavitte says, the results can be severe. “Two years where you’re assigned to a high school that you’re having a hard time getting to could really doom (students) – it’s two years, you’re not going to bounce back from that,” he says. “It’s not like a semester. It’s two years.”

Grant freshman Eric Vaughn-Matthews, who is white, lives about 10 blocks from Grant. “I’ll probably be driving by then,” says Vaughn-Matthews. “I feel like it’s definitely going to be pretty inconvenient, especially for people who don’t have cars. But on the other hand, we definitely do need to earthquake proof the building, so I think it’s worth it. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t going to be a hassle.”

Since Vaughn-Matthews’ family will likely be able to provide a car for him, the drive to school wouldn’t be as long. The Vaughn-Matthews family fits the bill of most situated close to Grant. The area tends to hold middle-class to upper-middle class white families that will feel much less of an impact from the move to Marshall.

On the other hand, Moore fears that her current eighth grader will be burdened with the move, but she doesn’t want to deny him the right to go to Grant based on her location.

“The key point is that we’ve just been historically late,” she says. “Like absent. I mean, at every teacher conference they complain. And a large part of it, it’s been me. But I live in North Portland and it’s hard enough to get them to school now.

“I assume he’d be on the MAX or bus, and that is a hell of a long trek. Like, ‘Oh, he’d be on an hour and a half commute?’ There’s no way. And so it’s extremely prohibitive.”

Gavitte is also concerned about transit options. He mentioned he wouldn’t be able to ride his bike to Marshall, which is his usual mode of transportation to Grant. “I’ll have to get a second car for a couple years. And that’s the other thing, buses down there are going to be difficult,” he says.

“The students that we’re most concerned about are the students who already commute from a ways away,” says Grant Vice Principal Kristyn Westphal. “I think for students who live in the Grant neighborhood — right around Grant — it obviously will take a little more effort, but I think it’s doable. But we also have students from further away, who already take two or three buses.”

Despite the magnitude of the move, PPS has not worked out a plan with TriMet yet.

Moore wonders if students will get help with transportation. “There is a federal law that says: ‘Every child is entitled to a fair, and safe, and equitable education,’” she says. “Transportation is such a big part of that. Especially with this, and it sounds like the district is just giving a quickie answer. Like, ‘Oh, well, we’re going to do this.’ Oh, really? Have you ridden the bus? Do you know what that means?”

Jim Owens is the senior director of the district’s Office of School Modernization, a department created specifically to oversee the implementation of the improvement bond. He says the district hopes to be able to cut a deal with TriMet by the time students are commuting to Marshall.

“The transportation plan is still a work in progress, in terms of exactly what that will look like,” he says. “The preferred plan is to continue with the TriMet bus pass system. That’s what we use in all of our high schools, of course. The initial plan would be to use that.

“However, we do want to have conversations with TriMet about adjusting some of the bus routes so that there would be a more customized approach to the Grant community using Marshall.”

A TriMet spokewoman said her agency hasn’t been asked by the district about bus passes for the 2017-18 school year.

Members of the Grant community know very little about relocation plans. The PPS Office of School Modernization finalized the Marshall campus as Grant’s relocation spot in December 2013. District outreach to PPS families was minimal.

“It wasn’t a fully developed community engagement process to determine the swing sites for either Franklin, Roosevelt or Grant,” Owens acknowledges.

After announcing the Marshall campus as Franklin’s swing site, Owens says time and budget constraints sped up the process pushed the district decision to have Grant students move to the same place.

“Franklin was relatively straightforward with the Marshall proximity and with the closure of Marshall,” Owens says. “For Grant, it was a similar thought process, but a little further away. But in both instances, we didn’t engage the community in that. After the bond was approved, it was something of ‘we need to message this’ and that was done at a meeting, and it was really a staff conclusion that this is what we needed to do.”

Moore says when she first attended a parent meeting in spring of 2014, the ruling was already final. “I felt like I had already lost my chance for a vocal vote,” she says.

Critics say the lack of collaboration with the community shows PPS determined Grant’s future in a vacuum. When the decision to include Grant in the 2012 bond was made, records show the district considered three options to house students during reconstruction.

The first choice was Marshall. Given the abandoned campus, the district felt it would make the most sense to relocate approximately 1,500 kids to an unused building after Franklin students left.

The second option was to stay on campus at Grant and build portable classrooms across school grounds. This option was costly – estimated at more than $7 million – and also conflicted with part of the campus that’s owned by Portland Parks & Recreation.

The third choice was to move to Jefferson, a North Portland school that historically has had some of the highest enrollment numbers for black students. Opened in 1908, the building currently has 321,354 square feet but just serves under 500 students. Grant currently has a population of about 1,500 students and a square footage of 274,489.

An Office of School Modernization memorandum from January 21, 2014, lists advantages and disadvantages of moving Grant to Jefferson’s campus. Owens says the memorandum is the principal document used by district officials for the analysis of alternative sites. One line stands out.

“A co-location of Grant HS at this location would create a campus with two distinct identities which have the potential to be culturally problematic,” the memorandum states.

In an interview, Owens struggled to define the term “culturally problematic.”

“I’m not sure what was intended on that,” he said. “I need some time to think about that.”

That perception by people outside Jefferson’s boundaries contributes to misconceptions about the school. “In the past, it has been rough, but it’s gotten better over the last couple of years,” says Jefferson sophomore Dylan O’Brien. “But the perception hasn’t changed on it since then. It’s frustrating.”

His friends at Grant “have never been near Jefferson,” he says. “They don’t know what it’s like.”

For Jefferson junior DeShawn Spencer, 16, the lack of attention to the Jefferson option speaks to an old stereotype. “Black people always get that negative look,” says the African-American student. “It sucks. It really does. It just doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. We’ve tried to make a lot of change and, of course, it’s working. But the process is taking a lot longer than it should have.”

If Grant students came to Jefferson temporarily, Spencer doesn’t feel it would cause too many issues. “I think it would’ve been really cool,” he says. “Give them the chance to see what Jeff is really like. I think a lot of people’s opinions would’ve changed.”

However, the district determined that Marshall would be the most reasonable option last winter.

“We’re fortunate in many ways that Marshall is available,” says David Mayne, communications manager for the Office of School Modernization. “There’s a lot of school districts that just have nowhere to go. So we have this facility that’s available, currently in really good shape and not being used. So it’s actually a nice asset to actually have.”

Jason Blumklotz is a white parent of Irvington students who are currently in third and fifth grade. He feels the district made the right choice with location. However, he says there are other issues that need to be addressed.

“I want to see them use this $95 million to rebuild the school,” he says. “But what if we took that money and we said: ‘Everything we do to this school has to be given to the kids first.’ Say to the kids: ‘You’re going to help do the permitting process. You’re going to work with city staff.’

“That’s a real job. And that’s a job that someone like me, who’s connected, can get. And one that the black, poor, brown kids can’t get, because they don’t know those folks. And we could be doing that right now. Schools can do that.”

Blumklotz says he feels that the relocation isn’t the biggest issue. “What’s the rebuild really about?” he asks. “We don’t want to just rebuild the building. We actually really want to use the building rebuild to actually change what we do for kids. That’s the important opportunity.

“If we just put the same name when we put (Grant) back together, we have missed a huge chance. A huge chance to really change equity.”

Owens says master planning for Grant’s modernization is set to begin in summer of 2015. Soon after, a design advisory group will be created to offer input throughout the entire process.

“The DAG stays with the project through design, and even when you get into construction, that same group still has a level of engagement but DAG is designed to represented different community constituencies,” Owens says.

Students and other community members can participate in the advisory group, he says.

Maria Carlsen, a senior at Franklin High School, has been a student representative for the Franklin advisory group since the end of sophomore year. She says it would have been better if more community members had been involved. “It kept going back and forth about when they were actually going to start,” she recalls. “And people kept coming up to me like, ‘Wait, are we going to have to go to Marshall?’

“Finally, something just came out saying, ‘If you’re in 9th grade, this is where you’ll be going,’ and I looked at it and thought, ‘That should’ve came out three years ago.’”

Owens says the district hopes to learn from any shortcomings they experienced in the Roosevelt, Franklin and Faubion planning processes. But he says the decision to relocate Grant students to Marshall is final.

“It’s not that Jefferson couldn’t be used,” Owens says. “It’s just that Marshall is a better solution.”

Yet, the bigger problem still remains: the district’s equity issue, which Blumklotz says resides with the fact that people simply don’t trust the district. “If you want to do change, you’re talking about trust and ownership, right?” he says. “So if I want change, I’ve got to provide opportunities for trust and ownership. How you do that, I think, is more complicated, but I wonder if the ways in which we think about it now are really effective. Are we really going to solve problems the way we address them now?” ◊