Summer transitions to fall and Grant Park is abuzz. The fields near Hollyrood School are filled with quick-moving players. Tennis players pound balls back and forth. And Grant High School’s new field is in full use as the football team practices next to older soccer players waiting for a turn on the turf.

On the north side of the park a worn, wooden bench sits along the path. It’s been the site of many lovers’ quarrels. Skateboarders have had their way with it. Runners have rested there after long practices.

A shiny bronze plaque with the names of Kate and Victoria Jeans Gail sits embedded in the ground in front of the bench. The simplicity of its design and the state of the bench don’t begin to shed light on the story behind the two women.

The bench is one of a number of memorials scattered across the Grant campus. Often, these landmarks get overlooked, as students and other community members make their way around the sprawling park. But they hold a high level of significance to the families whose lives were changed by loss.

“That was one of the things I learned as a result of this, is that everybody experiences loss,” says husband and father Kevin Jeans Gail says. “It’s not a matter of if, it’s just a matter of when. And it might be cancer, a broken relationship or a divorce, or a loss of a job. But it’s just something that we all have to deal with.”

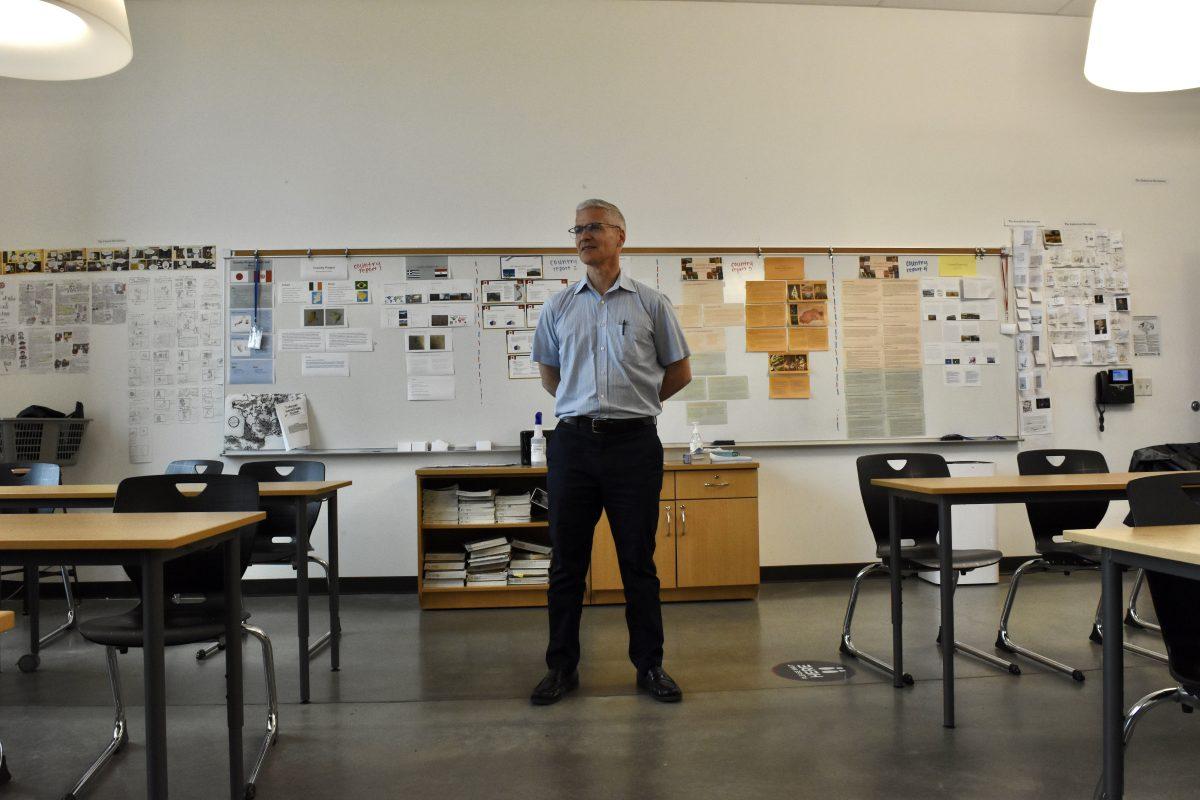

Jeans Gail is remarried now, but still lives a few blocks from the school. He runs a program called Portland Workforce Alliance, a small non-profit organization that helps connect high school kids with local businesses to provide youth with job experience.

Grant has two members on the alliance’s board of directors – Principal Carol Campbell and Madeline Kokes of the College and Career Center. Jeans Gail’s work has provided a number of students from the school with opportunities, and he’s a fierce advocate for combining these experiences with education.

But when the father of three recounts the story behind his family and how his wife and daughter were lost 11 years ago, his voice never falters.

“As you get older, you look back and you say things happen for a reason,” he says, recounting the first time he met Victoria.

It was 1977. Jeans Gail had only been in Portland from Chicago for a couple of weeks, got a call from a friend, asking him to come along to dinner with him and two other friends who were visiting from San Francisco.

The restaurant was on Swan Island but he couldn’t find it. After driving around for a while, he finally arrived. After about 45 minutes, he and Victoria were the only people left.

If Jeans Gail didn’t know from that first date that Victoria was the one, she certainly knew. As it turned out, the woman born in Modesto, Calif., worked for a nonprofit and shared similar values of community organizing to Jeans Gail. Two months later, she moved to Portland to become the administrative director of Oregon Fair Share. Less than a year later, they married. “I used to tell the kids the story that it was their mother who actually proposed to me,” Jeans Gail says.

Victoria Jeans Gail had a loving personality that rubbed off on anyone she would meet. Deb Kirkland, who met her in a parenting class, remembers how her friend would greet everyone with a hug, and usually “a big kiss on the cheek.”

In September 1979, the family welcomed their first child, Kate. Quickly, the new parents were in over their heads but hopelessly in love with their new bundle of energy. Jeans Gail remembers her as “strong-willed” and having a “mind of her own,” traits that wouldn’t abandon her later in life.

“We were wondering at times, would all the children be like this?” he says today.

The family lived near Legacy Emanuel Hospital. A park nearby was riddled with gang activity. They lived amid families that had few resources compared to their own. That’s where Jeans Gail believes a young Kate began to adopt what would be her life mission for social justice.

Two sons, Conor and Sean, followed and the Jeans Gails moved into a house around the corner from Grant. Victoria did bookkeeping independently for several non-profits. She served on the board for a time at Jesuit Volunteer Corps, which links young people with volunteering opportunities. She also served as a spiritual director, traveling with people on their spiritual journeys.

Barbara Scharff, a longtime friend of Victoria, still remembers the first time meeting her. “She had the soul of someone I felt like I had known my whole life,” she recalls. “I felt like I could just talk to her about anything and everything.”

As the kids got older, Kate took on the role of watching over her brothers during the summer. She would take them over to Grant Park to play basketball and soccer, and they would head to the Hollywood Library. They enjoyed talking about their favorite music.

Kate attended Beverly Cleary for middle school, where a teacher recommended St. Mary’s Academy for high school. There was some hesitation about private school, but after hearing the emphasis on community service and women’s leadership, Kate was sold.

The summer between her sophomore and junior year, Kate had traveled to France as part of a school trip. That’s when, according to Conor Jeans Gail, she caught a “travel bug” she couldn’t shake off. “She had a wanderlust,” Conor Jeans Gail remembers. “It’s hard to say what triggered her to not just travel but want to help people, too.”

She also had great luck, her family recalls. In September of her junior year, on her 17th birthday, Kevin Jeans Gail remembers dropping off an ecstatic Kate at 6 a.m. at the downtown Park Blocks. She worked as a volunteer for crowd control for President Bill Clinton’s long-awaited visit to Portland. Kate told her dad: “Today, I’m going to meet the president of the United States.”

Later that day, he got a call at work. A local newspaper couldn’t figure out how to spell Jeans Gail’s last name for the story they would be writing on how a crowd control volunteer – his daughter – had gotten a picture with President Clinton. Says Jeans Gail: “She wouldn’t be shying away from anybody.”

Her brother, Conor, remembers her sending out email threads about her hopes of doing mission work and asking for resources. She was outspoken, he recalls, and would easily get up in arms about the things she believed in.

As young kids, the Jeans Gails would deliberate with their parents about the Sunday church outings. Even though Kate was deeply spiritual, she took issue with some of the church’s beliefs and values. “The fact that we were being forced to do it certainly kind of struck a chord with Kate, because she believed in personal freedom and all of that,” Conor recalls.

When their more conservative – and wealthy – East Coast family would pay a visit, Kate would get into arguments, pushing her more liberal perspective.

With age, her opinions and beliefs were put into action. She attended Smith College and studied anthropology, with an interest in public health administration. She and her friends, some of whom went on to pursue medical careers, had dreamed since high school of one day opening a clinic for the underserved.

In the summer after Kate and her friends returned from their first year of college, friend Miki Greenlee remembers how Kate wrote out an entire calendar planning their summer escapes. They would hike, take day trips and go on road trips.

Two summers later, after her junior year of college, Kate upgraded her ambitious travel plans. This time, she put Calcutta, India on the list in order to work with Mother Teresa. She and another friend, Kori Pienovi, raised almost all of the money for the trip by themselves.

In Calcutta, where Kate spent an entire month, she split her time between an orphanage and a home for the dying. “It was really eye opening. It was such an adventure,” says Pienovi.

Kate later wrote in a journal entry that ran in The Oregonian that “in both places I am changing diapers, feeding and holding. No doubt, the circle of life…I talked and listened and held a lot.”

She later travelled to Morocco to be in the Peace Corps, while there sending long letters to family and friends. She also always carried around a camera.

She did everything to immerse herself in the culture, even observing Ramadan by fasting for 30 days. She wrote a grant that got funded to open a women and infant’s health clinic in Southern Morocco.

In spring of 2003, Kate began to work for Teach for America in New York City. That winter, she came home for the holidays.

Victoria Jeans Gail’s friend, Scharff, remembers exchanging squash soup recipes before wishing her a happy holiday season. “She just looked so vibrant,” Scharff recalls. “And I’ve had that image in my mind so many times.”

Pienovi, Greenlee and several others went out with Victoria and Kate the night before they left on a trip to Central Oregon. While driving to Bend on Dec. 28, Kate and Victoria Jeans Gail hit a patch of ice. Their car spun out and collided with a sport-utility vehicle. Both women died.

Family and friends showed an outpouring of support. But the loss was crippling. The next Christmas, the Jeans Gails didn’t follow their usual tradition of cooking lobster or going to chop down a tree. They went to Mexico because staying in Portland was just too hard.

Kevin Jeans Gail “doubled down” on his faith and remarried in 2007 with Conor as his best man. The deaths held a big impact on Conor, who says he learned to be politically conscious from his sister and to treat everyone fairly from his mother. “That was always a big one for me…the way that they affected me after even they died,” he says.

ack in Morocco, a nursery of fruit tree saplings was planted in her honor. The trees serve as an opportunity for economic growth for the poor surrounding community, something both women would have supported. This last January, the millionth tree was planted. Closer to home, Grant Park seemed like an ideal spot to remember the women. Deb Kirkland explored the idea of dedicating a bench. At the time, no benches at Grant were dedicated, Kirkland remembers. Neighbors, co-workers and friends all pitched in to have the bench built and the plaque made.

Now, the bench is one of many dedicated benches in Grant Park. Most of these memorials are somehow connected, even if by the loosest strands. The Jeans Gails knew Heidi Moore because she coached Conor’s basketball and soccer teams. Her bench sits just next to the Jeans Gails at the mouth of the park.

Moore’s husband decided the bench would be a fitting memorial because of its proximity to Kate and Victoria’s memorial. She often sat on it. Moore, who graduated from Grant in 1974, studied nursing at University of Portland and later worked as a nurse for Providence Hospital for more than 30 years. She visited patients at their homes as a home healthcare nurse. In later years, she taught at the school of nursing at Concordia University.

Her son, Jake, a 2005 Grant graduate, was raised in a single-parent household by Moore. He says she knew from the beginning that she wanted to be a nurse. “She was always really caring,” he says. An avid runner, Moore would often be sighted running through the neighborhood and doing hill repeats on Northeast Wisteria Drive, her long, blonde ponytail bobbing as she moved along. Mercedes Loprinzi was a long-time neighbor who also knew Victoria and Kate Jeans Gail. She remembers that after being diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2008, Moore was not able to run anymore. She lost her bright, bobbing hair, too.

Moore maintained a positive outlook, taking long walks with Loprinzi, which often ended with them meandering through the park past the Jeans Gail bench. “We shed some tears, but most of all we shed laughter,” Loprinzi recalls.

In 2011, Moore was able to attend Jake’s graduation. By then, she had remarried and was nearing the end of her life. She died in August.

Another auspicious memorial sits at the front of the school – two benches that serve as a testament to Grant students, Claire Van Engelen and Andrea Perez. In 2004, Van Engelen and Perez were killed in a car accident on their way to the Oregon Coast, just days before the start of their promise-filled senior year. Claire “taught me to smile and laugh with reckless abandon, to work hard and play hard, and to be open and accepting of all people,” Keeley McAnnis-Entenman, a friend of Claire’s wrote in a recent e-mail recalling her death.

Kelley Parker, who was friends with Perez, remembers her for being intelligent and outgoing.

In a hope to honor both girls, the student government that year decided to create the honorary benches. Cindy Zyrini, the head teacher in the medically fragile class at Grant, used to be the activities director when the girls attended Grant. She remembers the families visiting the benches for the first time. “It was a sad-happy of course,” she says.

Both McAnnis-Enteman and Parker got tattoos to commemorate the lives and values of their friends. Parker’s is an “A” for Andrea with a halo and a set of wings, and McAnnis-Enteman’s is a Maori symbol that stands for “strength, determination and new beginnings.”

The impact of the benches on the survivors – even after years of use – still resonates today. Says Jeans Gail: “The bench itself has been a wonderful gift because it’s life giving to go to the park…That was our community, that was our lives together.” ◊