Back in freshman year gym class when Eli Orton-Brown’s classmates had free time, things took a turn for the worse. A group of boys began slinging taunts. This wasn’t the first time, but the abuse was getting physical – all because they had a problem with Orton-Brown dating a girl.

The summer before, Orton-Browns had officially begun identifying as “queer.”

“I realized I liked both girls and guys,” Orton-Brown explains, who is a junior.

Gender-wise, Orton-Brown identifies as androgynous, embracing a gender-neutral style of clothing and appearance. Finding the right word to identify sexual orientation proved to be troubling. “I had thought I was bi, then lesbian, then bi, pan, and now I’m just queer. Queer is just a word that makes sense to me.”

For Orton-Brown and many other teens, coming out and openly embracing the LGBTQ community can be risky. One-third of transgender youth have attempted suicide, and 78 percent of LGTBQ teens are teased or bullied based on their sexual orientation. As these numbers grow, so do the rates of attempted suicides.

But bullies don’t deter Orton-Brown, who, despite the attacks, maintains a peaceful nature and finds ways to spend time with people who understand.

Grant’s Gay Straight Alliance president Lindsay King says a lot of words can be used to describe people in the LGBTQ – an acronym for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer community. Some of the words negative connotations, especially when it comes to pop culture. “The phrase ‘That’s so gay’ is used all the time,” King says. “It’s like they think ‘Oh, I’m just joking.’ But when someone in the LGBTQ community hears it, they think: ‘Does this make people not like me?’”

When Orton-Brown came out, her mother, Ariana Orton, wasn’t surprised. “I understand it’s not a choice,” she says. “It’s how your body is. And you know, she’s my kid. We just want her to be happy.”

Keeping an open relationship with her kids helps make the family home comfortable and safe for Orton-Brown. Ariana Orton says she has made it a goal to ensure her children feel like they can tell her anything. “If your kid doesn’t feel safe talking to you, they won’t feel safe about talking about other things,” she says. “I see it as a huge safety risk.”

Others in the family had a harder time coming to terms with Orton-Brown’s sexual preference and identity. Orton-Brown says her dad’s side of the family is very open to it, but her mother’s side has Mormon roots, which creates a block. “My mom’s mom ignored me when I asked her how she would feel if I brought a girl to dinner,” Orton-Brown admits. “I didn’t bring it up again.”

No one would ever guess Orton-Brown comes across such hard times. To see Orton-Brown in the halls or anywhere else, you’ll encounter someone who usually has a bubbly outlook on the world. When a song pops into her head, she feels free to sing it. When creativity strikes, she feels free to draw and share her work online.

Today, Orton-Brown seems incredibly unflappable and without limitations. But things weren’t always this way.

As a student at Waldorf School, Orton-Brown endured about a year and a half of bullying and troubling instances with an ex-boyfriend. What troubled her mother the most was that no one at school even brought it up. Once she found out, they moved Orton-Brown to another school.

Having dealt with bullying and harassment before, Orton-Brown knew enough not to let the situation at Grant “get bad.” The incident went to the P.E. teachers and her parents, then to the counselors. “I didn’t see anything happen when I sat in,” Orton says. “I didn’t expect to. The mice behave differently when the cat is in the room.”

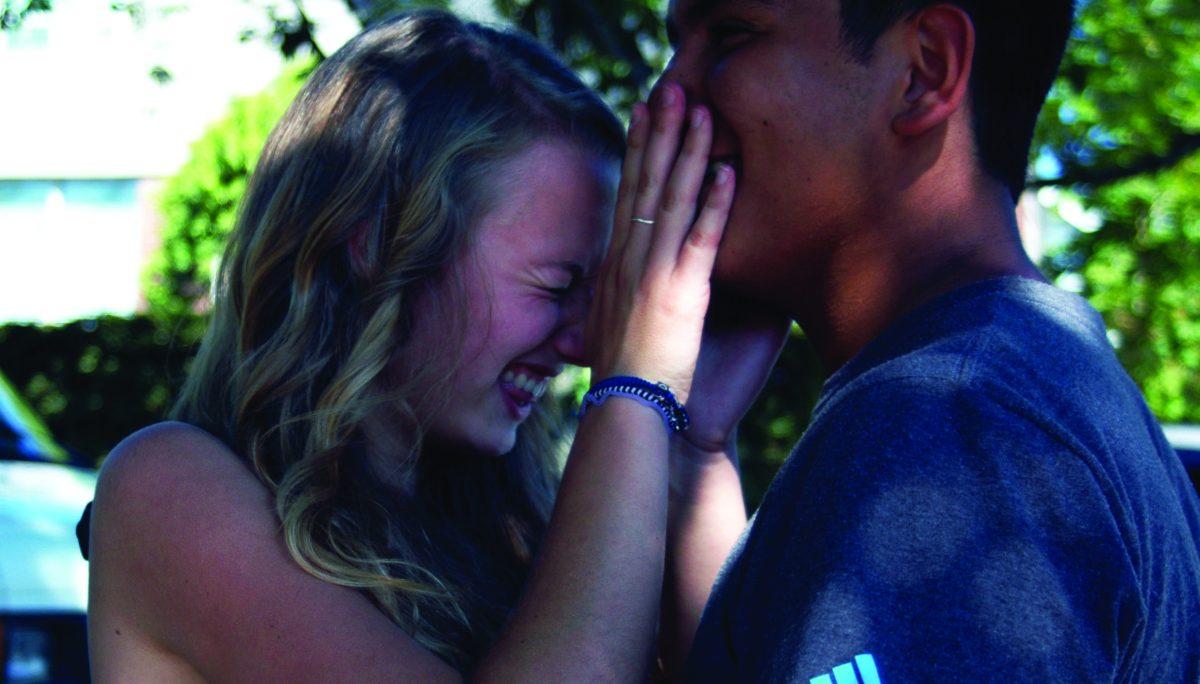

Orton-Brown admits some boys say things to her if she’s alone, but Grant remains an enjoyable place because it’s a safe environment where she connects with like-minded students. “We have millions of inside jokes,” Orton-Brown says. “We talk about a lot of things and just hang out,” Orton-Brown laughs. “We talk about things that will help the LGBTQ community in America.”

King says she wants the GSA to be a place that helps promote understanding. “People became aware of GSA and saw it as a safe haven for LGBTQ,” King says. “I feel like the people who are in GSA who are part of the sexual minority are comfortable in who they are.”

Beyond Grant, Orton-Brown wants to study in Tokyo, Japan. A student of Japanese, Orton-Brown has a fascination with anime. In the future, the plan is to have some surgeries to modify her gender. This will help Orton-Brown feel more in sync, with the end result would being a body that meets somewhere in the middle.

Orton-Brown is also trying to buckle down on how people refer to her. The teen discovered a set of pronouns used by many in the transgender community. “They’re slightly altered versions of gender-specific ones,” Orton-Brown explains.

Some examples from the Internet include xe, zher, xemself, zhe. Usually, people just refer to Orton-Brown as “she” because it’s convenient. “I sometimes get upset by that,” Orton-Brown says.

Overall, things look promising for Orton-Brown. Two years of high school are over and the student remains undeterred. “I have an open mind when it comes to how I see the world,” Orton-Brown says.

Indeed, while other parents worry about their children behaving suspiciously or giving in to peer pressure, Orton has no concerns about her child. “All the things I thought I’d have to deal with for a sixteen-year-old girl, I don’t,” she says. “She’s always been grounded.”

Orton-Brown just ignores people who mistreat her. The best philosophy? It’s all about the company you keep and who you surround yourself with. “I don’t meet very many closed-minded people,” Orton-Brown says. “And when I do, they aren’t for long.”