A daughter comes to terms with how life will play out in the future.

It is Christmas Eve. I’m seven. My dad and I wait to take the No. 77 bus to the Hollywood stop from his downtown office. My small hands are buried into my coat pockets.

It’s an inconvenient way to get there: waiting 10 minutes for the bus to arrive, wind nipping at any exposed skin, and having to stop every few minutes for new passengers to board. Mom could have easily just driven us. But I knew that would ruin this tradition.

When we get off the bus, we fulfilled the annual trip: stocking up on candy at a nearby Rite Aid, making the mile walk home, and then squishing together on the couch as a family to watch “The Grinch.”

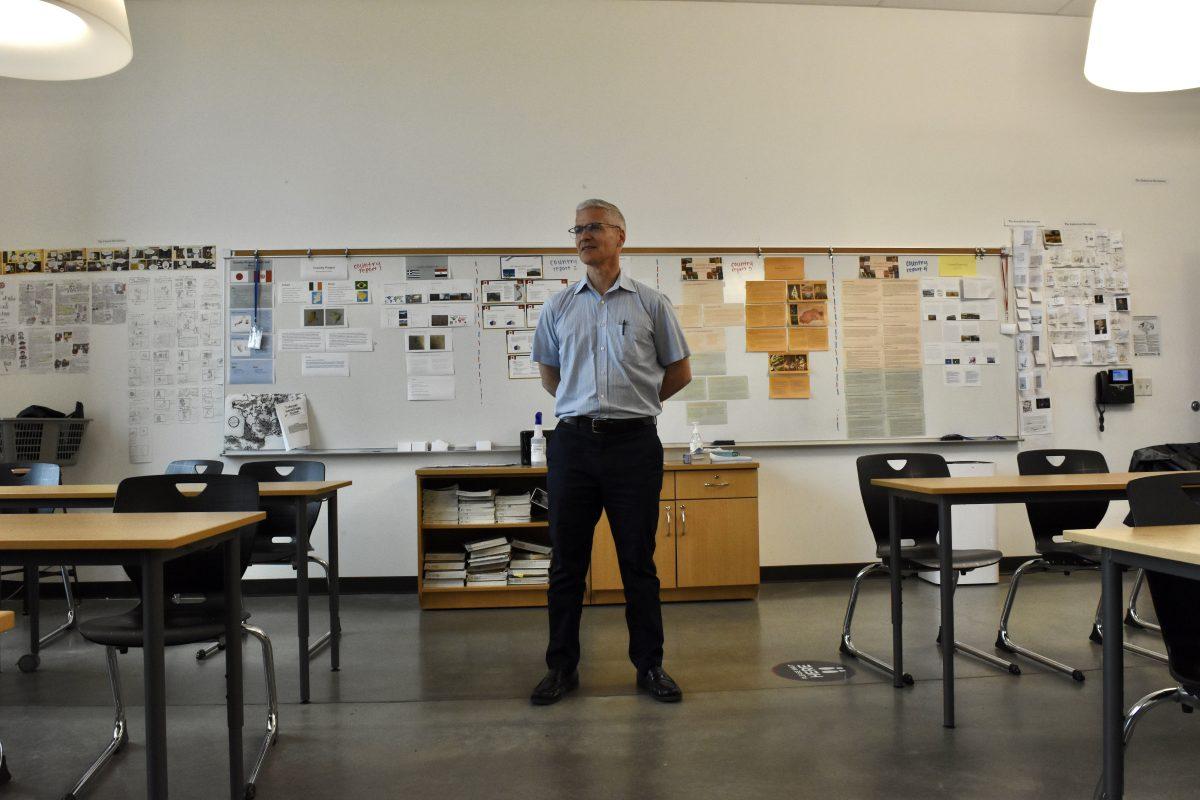

My dad always sits in the same spot, resting his arm to hold up the special glasses he wears to view the screen. He sits closer to the TV than the rest of us.

He has macular degeneration. It hard for him to do many things – read, watch TV or a number of the things we take for granted.

Like most people, the disease was foreign to me when I first heard it. All I knew was degeneration meant losing something, and nothing good could come of that.

Macular degeneration causes a slow deterioration of the retina, making central vision ineffectual. People who have it are forced to rely on their peripheral vision, which can be blurred. As his eyesight worsens, he may eventually go blind. More than 10 million people in the U.S. suffer from macular degeneration. There is no cure.

I spent a lot of my childhood worrying my family would be consumed by it; I thought that my dad’s disability would create heavy drawbacks to our lives. I couldn’t understand why it had be our family. I didn’t want people to see my dad and only think “disabled.” Just like with any other family, I wanted him to be known for his hard work and passion for his job and the things he loves.

To this day, I don’t want a disease to alter people’s views of my father.

With three older brothers, I knew what toughness was before I could even walk. Growing up, my family has shown me to live with what life throws my way. It’s always been my parents’ priority to never have his disease treated as a big deal.

Out of my grandpa’s 13 kids, my dad was the only one who inherited the disease. It started to take effect when he was in high school and has progressively worsened since. Now, seeing my grandpa is like a look to the future of where my dad will be someday. I picture my own kids greeted by my father and wonder how well he’ll be able to make out their faces.

When I was younger, while most parents read to their children, I read to my dad every night. I waited for him to get home so we could finish the “Little House on the Prairie” series together. My dad would tell me about his childhood, growing up on a farm in Canada.

He told stories of chopping wood and harsh winters walking to school. Though Wilder’s childhood and my own don’t share much in common, I’ve always felt a deep-rooted connection with her and the memories she’s created for me and my dad.

I always knew my friends’ dads weren’t like my own: my dad can’t drive, his phone’s font is blown up for him to see and he uses a machine to zoom in on small print. I never felt inclined to explain to them what my dad was going through. I didn’t want our family to be known simply because of my dad’s disease.

I didn’t want people to feel pity for something that’s so normal to me. I have never liked the way my stomach starts to churn when people feel sorry for me. I have never liked the way it’s left me with this odd sense of weakness. I have never wanted to feel vulnerable.

My dad has accomplished a lot despite his affliction. He’s opened three breweries, completed more than 50 marathons and runs his own business. Often times, it’s hard for people to believe such a barrier even exists.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve seen that my dad’s macular degeneration doesn’t need to be a defining piece of who he is as a person. It doesn’t need to reflect on my family as a whole. And it shouldn’t change who he is to others.

My family will always help my dad when he needs something. I’m still bracing myself for the time when his condition worsens. But right now, that doesn’t matter. I know my dad has the power to overcome obstacles. He does it every day. ◊