Randy Heath’s eyes look protectively over his granddaughter, Drea Nelson, who is dressed head to toe in pink. Her signature pair of braids flop up and down as she chases a soccer ball across the field while her grandfather wraps up coaching for Grant’s varsity football team. Heath, age 49, watches as her infectious giggles die away and her jolting walk comes to a stop. At 5 years old there is little that can keep Nelson still, but today something has caught her eye. Her gaze stretches across the field as she watches a few kids her age start soccer practice.

“She wants to play so badly with them,” remarks her grandmother, Andrea Heath. Nelson takes a few steps toward the game but lingers on the edge of the field. She knows just as well as her grandparents that she can’t join them. “She will be on the fringes and she will watch everything,” explains Randy Heath. “No real interaction, but she does really want to play soccer.”

Nelson suffers from an undiagnosed disability that falls under the category of Global Delay. Though she is 5 years old, she has only been able to walk for three years and has trouble stringing more than three words together at once.

None of this seems to bother Nelson at the moment, though. Her grandfather is here and she can’t wipe the smile off her face.

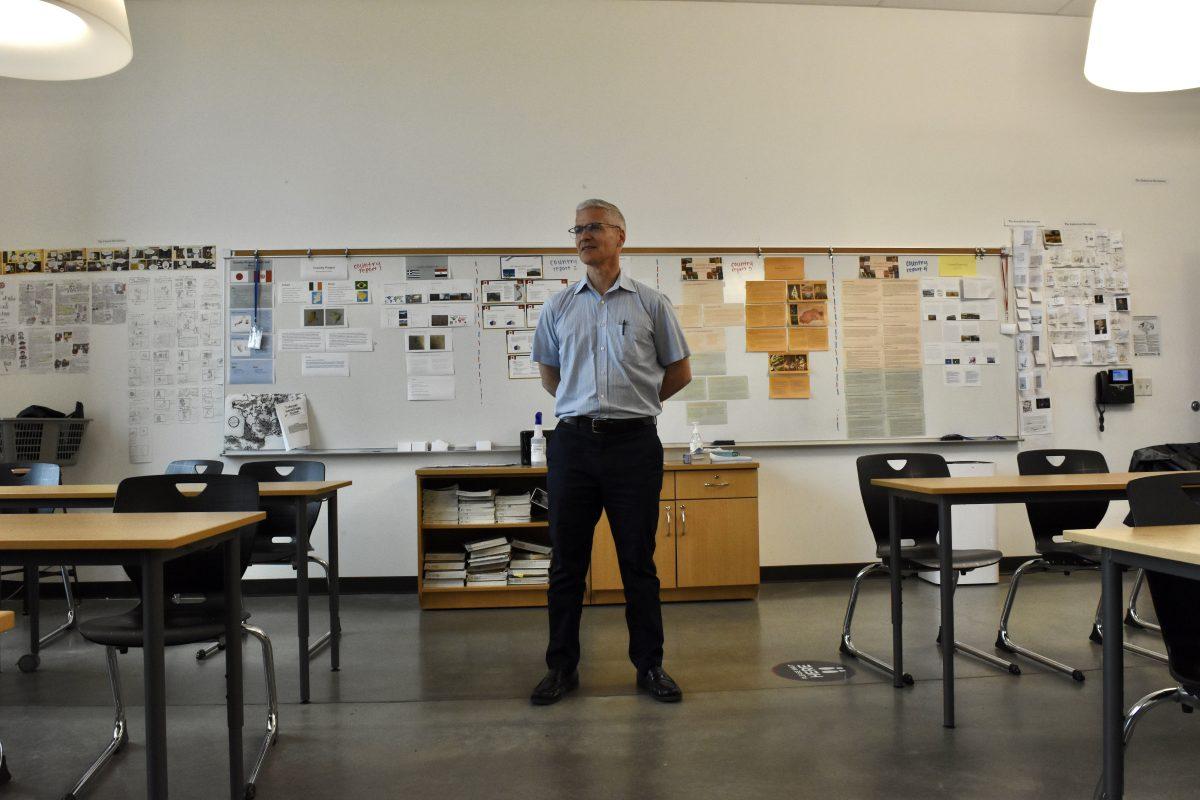

Heath, a current Grant High School health teacher and varsity football coach, has dedicated the last three years of his life to taking care of his granddaughter. Using his background as a coach to guide him, he has worked tirelessly to help Nelson exceed the limits of what her disability dictates.

Born in Medford, Oregon and raised by a single mom, Heath has always had a strong connection to family. “(Having a single parent) was probably not normal for Medford but my mom made it normal,” Heath explains. “She did all of the things that the overbearing fathers did in the town.” Looking back on his childhood, Heath is grateful that his mother took on both parental roles. He even sends her an annual Father’s Day card to acknowledge the part she played in his life.

As a child Heath played every sport he could. Starting in fifth grade he played football and in high school he began to play basketball and baseball. Sports were the focus of Heath’s young life and he greeted each one with a fierce dedication.

His mother, Loretta Molano, recalls how, despite the nauseating migraines Heath experienced throughout high school, he would scarcely miss a football practice. “He would sleep for 20 minutes and then get back up and finish football,” Molano explains. “He got to play because he wouldn’t give up; he kept working.”

Molano remembers Heath’s determination even when teams would turn him down. After not making the cut for a summer league baseball team, at age 15, Heath decided to become their team manager instead. When a few players dropped out of the league, Heath had proved his dedication and was invited to join the team.

After starting work at a mill the summer before his senior year and receiving a partial scholarship, Heath was able to play football for Linfield College. There Heath’s coach, Ad Rutschman, took a special liking to him. As Heath describes it, Rutschman modeled the patience and fair treatment that Heath now strives to include in his coaching. “He is one of the most intelligent football coaches I have ever been around and the way he treats people is amazing,” says Heath. “As a coach, all I have ever tried to do is to treat people the way he treated me.”

Influenced by his love for the sport and a hunger to influence kids, Heath decided to become a coach. After college he coached at a multitude of schools in the Oregon area and for him, it was paradise. “The chance to be a positive influence on kids your age is huge,” he says. “It lets me still be a kid for a while.”

For Heath the best part about being a coach is the ability to help kids through any obstacles that they may face. “I expect a lot out of the players that I coach,” he explains. “ I expect them to work hard, but I guess I try to push them to expect more out of themselves.”

Though he may appear intimidating on the football field, Heath is known for creating a strong bond between himself and the players. “Randy is an educator in the true sense of the word,” says Ken Potter, Heath’s former colleague who currently coaches at Jesuit High School. “He teaches you how to play the game.”

Coaching has become a big part of Heath’s identity. Through the years, he has formed a community of colleagues and former students that hold him in the highest regard.

“Whenever hard times come up or I have a difficult decision to make, he has always been there. He has always told me that I can call,” says Jake Wark, one of Heath’s former athletes from Jesuit High School. Recently, Wark left U.C. Berkeley to play football at Oregon State. He attributes a big part of this decision to the support he received from Heath.

“He really has a desire to see (his students) go on and succeed as men and women,” explains Jake’s mother Pam Wark.

Though Heath’s afternoons were always dedicated to coaching, family always took priority over football. When his daughter began to worry about Nelson’s health, Heath knew he had to step in. “He’s been there since we found out something was wrong,” explains Kaitlyn Heath, Nelson’s mother.

From nine months old on, Nelson was not hitting the benchmarks for her age. As she got older, her body continued to grow, but her mind couldn’t seem to catch up. Initially, her family began to notice small setbacks that were a cause for concern: she wasn’t speaking when expected to, was not crawling early enough, and was behind in walking. It became evident that something was wrong. “The longer we (waited) the more it was obvious,” explains Heath. “She’s not hitting benchmarks.”

Nelson underwent a series of genetic tests as well as physical and occupational therapy. As she turned two, her mother graduated from beauty school and was offered a full time job at a salon. In order to support his daughter’s career, Heath made his decision: he was going to take care of Drea.

“I wanted to make sure she was at appointments, I wanted to make sure we did our best for whatever her needs were and I wanted to make sure that my wife and my daughter did not have to make a decision based on having to care for her,” explains Heath.

For three years, every day started the same way. Heath would wake Nelson up, and using a tool that resembled a kitchen sink scrubber, he would brush her skin and limbs in hopes of stimulating her senses. Then, he would spoon feed her breakfast, bathe her, dress her and usually watch a couple episodes of Sesame Street. “He probably knows every episode of Sesame Street there is to know after the past three years,” remarks his wife.

Next, they would get in the car to drive to one of Nelson’s appointments (speech therapy, physical therapy or occupational therapy) and then make their way to preschool. Finally, they would come home and Heath’s real work began — he became her coach.

From playing games with Nelson, improving her motor skills, to taking walks with her every day, Heath took Nelson’s health into his own hands. “He would take what the doctors would say and then expand it on what he could do,” explains his wife.

The repetition that Heath implemented in his coaching was key in taking care of Nelson. Almost every day, they would go to the park and practice going up and down the stairs. Initially, he would have to hold one of her feet down and move the other to the next step, but eventually, Nelson was eager to run up and down any staircase she could find.

Heath was constantly trying to find things that would grab Nelson’s attention and benefit her health at the same time. “Everything she did kind of had to be based off of what her interest level was, and if she wasn’t into it that day, you were not going to force her to do it,” he explains. “It was solely dependent on how much she wanted to do.”

Some days, Heath had to accept that progress was not going to be made. If something frustrated or upset Nelson, she had limited ways of telling her family what it was.

“You can see in her eyes. She knows exactly what she wants to do and what she wants to tell you,” says Pam Wark. “She just has some sort of miscommunication with her brain and her body to try to get it out.”

Throwing things, going limp on the ground or even going into hysterics were all in the realm of possibility. Sometimes, Heath had to throw in the towel and try again the next day. As a coach, he knew that if he wanted results, he would have to stay dedicated.

Slowly but surely, Nelson’s health began to improve. After seeing the progress she had made, their physical therapist told the family that Nelson did not need to see him anymore. At home, Nelson found new ways of speaking with the family. By using bits of sign language and a few words she was able to communicate on a new level.

“She will come take your hand and say ‘Help’ and take you to what she wants,” explains Heath.

Today, Nelson is into her first couple months of kindergarten and is doing better than anyone in her family could have expected. “She has kind of jumped all of the hoops that we were worried she would not be able to do,” explains his wife.

In school Nelson has adopted a quiet and observant nature that is slightly different from the giggly personality her family is used to seeing. “She still sits back and kind of observes and watches the other kids,” Heath explains. However, after a month of school Nelson walked out of class hand in hand with a new ‘boyfriend’, who proceeded to cry when they had to go separate directions.

Now that Nelson is at school, Heath has become a varsity football coach and health teacher at Grant. Though he is overjoyed to be back on the field, he can’t help but miss all the time he used to spend with Nelson. “We just kind of had our own funky little relationship which was about the time we spent together,” he says.

Even though they don’t see each other every day, Heath’s effect on Nelson is still present. The moment Nelson sees her grandfather, her eyes light up and a smile spreads across her face. One of the only places she sits still is at a football game.

The whole family agrees that taking care of Nelson has taught them something. When she completed the sentence “I want Jell-O” in speech therapy, the whole family knew by the end of the day. “She brought our family down to this place of really (appreciating) what’s important in life,” explains Heath.

Despite the progress Nelson has made, her future is unclear. Without a concrete diagnosis of her disorder, her family has no way of knowing what she will be capable of in the future or even how long her life will last. In the next 12 months, Nelson will go in for her fourth round of genetic testing with the hope of finding out more.

“We just want an answer,” says Heath. “We just want something to be able to put our finger on and say, ‘That’s what it is.’”

Though there is no telling what Nelson’s future holds, Heath and his family are prepared to support Nelson through any new obstacles she may face.

“There are times in the last four or five years that it would have been really easy to just throw our hands up in the air and say ‘That’s it, I’ve had enough,’” says Heath. “I think the coaching side of it, not just for me, but for everybody, has just kind of kept us in the game.”