On most Sundays, Doug Winn, the 64-year-old head coach of the largest high school cross country team in Oregon, gets out of bed early for a bike ride. He tiptoes downstairs, grabs the bike that was given to him six years ago as a retirement present from the Grant High School faculty and hits the road.

Winn, who just finished another successful season as Grant’s coach, rides along the Columbia and Willamette rivers on a 40-mile bike ride. He uses the time to draft emails in his head that he’ll send out later in the day.

The bike ride and his runs during the week keep the head of the self-described exercise junkie clear. “I might run a four-miler in Laurelhurst Park,” he says. “I define myself as a runner. I have a certain sort of standard. It’s non-negotiable. I may check the weather and work around it, but no matter what, I’m gonna go.”

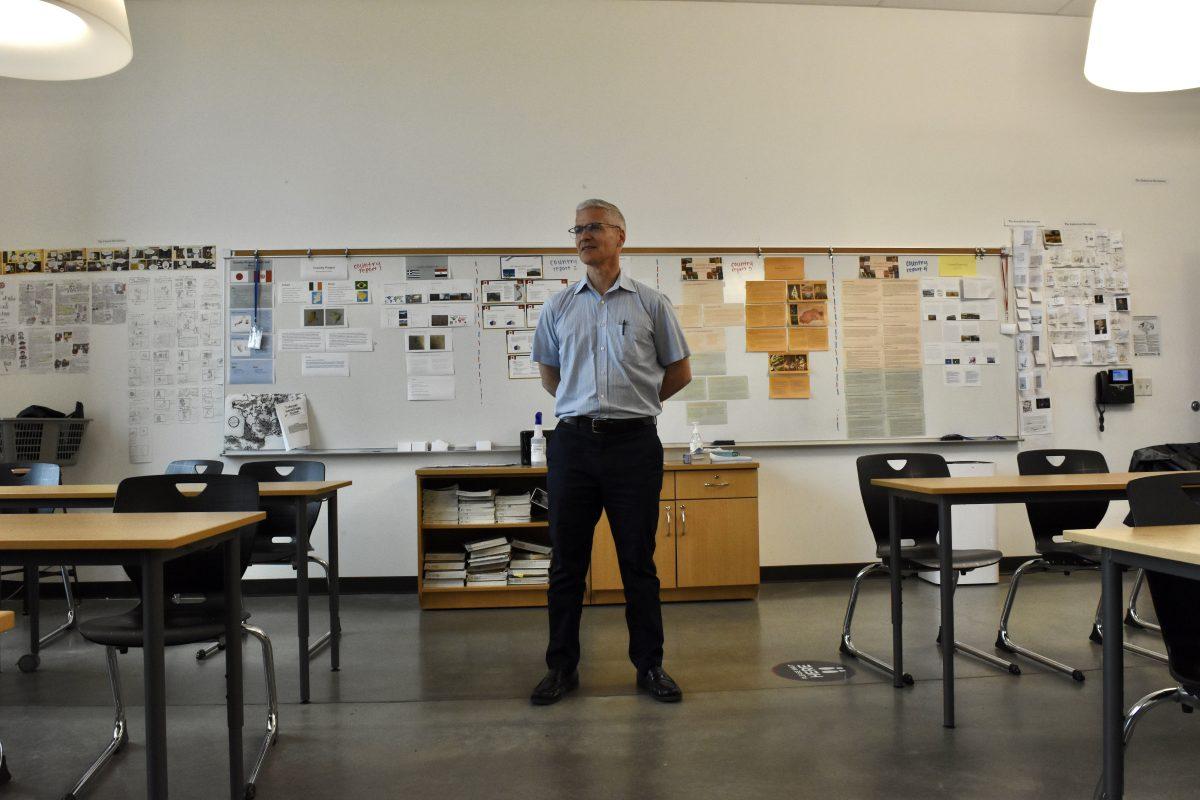

It’s a standard he holds for his teams, too. The man who took over as head coach three years ago and turned around a middle-of-the-road program demands the same effort from his runners. When he became coach, the team had about 65 runners for the girls and boys teams combined. Today, the numbers have swelled to 170.

But unlike other coaches, what makes Winn special is his ability to motivate with a quiet demeanor.

“I’m definitely much more confident in who I am as a person in more than just sports” because of Winn, says senior Martin Chasehill, 17, who was on the cross country team all four years at Grant.

During the cross country season, almost every day is filled with some type of involvement with the sport. He handles fundraising. He connects with parents. He wanders the halls at school providing encouragement on race days to his team members. It’s no wonder he often finds himself asleep in his recliner by 7:30 p.m. “I swear it’s coaching,” he says. “I couldn’t really tell you where the time goes but it’s a ton of stuff for my team.”

Winn has committed himself to everything he does, particularly his work with youth. “I’m just really driven to have an effect on young people,” he says. “You just get so much more energy when you see that happening.”

His childhood, on the other hand, differs from the students he mentors. Born on Feb. 2, 1950, in Martinsville, Virginia, Winn grew up in an extremely religious household. His father worked as a traveling evangelist and wasn’t around much. They believed in the Bible from a literal standpoint and valued the mission of spreading its message.

“They wanted to convert people to a very narrow ideology,” he remembers. “I want to do just the opposite.”

When Winn was 8, his parents split up and he moved with his mother and three siblings to Portland. He attended elementary and middle school in Southeast Portland.

To support the family, Winn’s mother – who had remarried – worked full time in a department store. The job left little room for her to take care of day-to-day responsibilities around the house, so Winn picked up the slack. Despite being the youngest, Winn’s energy and love for helping others allowed him to step into her shoes.

It wasn’t exactly the easiest role to play, especially with the high expectations that ran in Winn’s family. He remembers a time when his stepfather made him hold glasses he had washed up to a light bulb to check their cleanliness.

Before he started high school, Winn and his family moved again, this time to Oregon City. At Oregon City High School, Winn found his niche on the cross-country team.

Even as a teenager, Winn’s work ethic was above average. “I prided myself senior year – 58 days never doing a lick of homework,” he recalls, noting that he finished high school with a 3.8 GPA. Instead of taking it home, Winn would cram it into every second of downtime in class.

This dedication carried over to running. He joined the cross-country team as a freshman, but he stood out for all the wrong reasons. “I was the worst kid on the team,” he explains. “At some point, the light bulb went off in my mind that most of this distance running is effort. It’s how much you want it. I wasn’t blessed with fabulous genes, but I did have a very strong will to win, and before long I started doing just that.”

Instead of riding the school bus home, Winn used it only to transport his trombone and books, running four miles in oxfords and slacks to meet the bus at the stop by his house.

“I was just unusually ambitious,” says Winn, who made varsity his sophomore year.

His hard work paid off when he got into Cornell on a scholarship that he believes was related to running, even though Ivy League schools aren’t officially allowed to give athletic scholarships.

College was a game-changer for Winn, who felt that his religious upbringing had left him little opportunity to craft his own worldview. “I’m really glad that I got to go back East for college, because it gave me space to make my own judgments,” Winn says. “It was really a moment in my life where I got to reconstruct my world.”

Winn graduated in 1975 with a degree in philosophy. His first job was as a psychiatric aide at the Oregon State Mental Hospital, which he found on a whim when he was on his way to apply for a job at Sears. They would take anybody there for security, Winn says, but after he passed the nurse’s test, he was allowed to pass out medication.

At the hospital, Winn worked with adolescents. He separated himself from the other employees who would often smoke cigarettes while the patients sat idly by. Instead, he tried to get the kids he worked with out of the institutional setting.

Unfortunately, their existing circumstances made it difficult for Winn to make a real difference, he says. He remembers patients feeling that their mental illness deemed them “too broken to be helped.” His time there ultimately convinced him that he wanted to engage with teenagers as a career.

Winn considered social work or counseling, but his love for English drew him to teaching. He received his teaching certificate in 1979 from Portland State University. During this time, Winn met Annie Tracy when she took music lessons from his roommate. The first thing he remembers about her is hearing her sing.

They became friends before she moved around to California, Colorado and Canada. After receiving his teaching certificate, Winn found a teachers’ conference in Boulder and followed Annie there. It wasn’t until she both moved back to the Northwest, summoned by family, that they became a couple. “He’s a person that makes things happen,” Annie Winn says now.

They had two children, Daniel and Emily, who both went to Sunnyside Environmental School and later Cleveland High School. Winn approached parenting with the same enthusiasm that can be found in every other aspect of his life.

As a father, he encouraged his kids to pursue any interest they found. Dinner conversations typically consisted of politics. He regularly took the family to museums and lectures. When Matt Groening, who created “The Simpsons,” came to talk in Portland, Winn made sure that his son got a chance to talk to him face-to-face after the presentation.

Another important element of fatherhood for Winn was making sure he treated both children equally, regardless of their gender. “In his mind, I could be whatever I wanted,” says Emily Winn, who is 19 and a sophomore at Vassar College in New York. “He didn’t limit me in any way.”

Winn’s children both ran varsity cross country at Cleveland, though he was careful to not push running onto his kids. “He just has a real enthusiasm for the coaching side,” explains Daniel Winn, 23. “He’s really able to empathize with a large number of runners.”

Winn became head coach at Cleveland High School during Daniel’s senior year in 2010 when Daniel took home the state 5A championship for both the 1500- and 3000-meter runs.

While his kids grew up, Winn was teaching at Grant, where he started teaching English in 1986 after a faculty member had a heart attack. He did his best to go above and beyond. Instead of writing comments on student’s papers, he would record them on a cassette tape and express his comments verbally.

His lack of free thought as a child motivated Winn to get students to analyze the world around them critically and deeply. It was crucial for Winn not to impose his ideas onto students, but to teach them to form their own opinions.

In 1994, he became an assistant coach on Grant’s cross country team. In 2011, Winn was named head coach of Grant’s team after the previous coach retired. Since he began, he’s been able to expand the team dramatically. When the numbers started to swell, some teachers and administrators referred to him as a “Pied Piper” for running. He has a self-proclaimed addiction to recruiting, but his innate ability to make every runner on the team feel included is what keeps kids around.

“With a team as big as ours, there’s just a ton of kids breaking down barriers and doing better than they ever dreamed possible,” Winn says. “It’s fun to be a part of that.” ◊