During lunch on Wednesday, Dec. 3, Grant High School’s Black Student Union launched a demonstration in commemoration of the death of Michael Brown and other black men who have fallen dead at the hands of the police.

For four-and-a-half minutes, a circle of Grant students remained silent in the school’s Center Hall – a time signifying the number of hours that Brown’s body was reportedly left untouched on the streets of Ferguson, Mo., on Aug. 9 after white police officer Darren Wilson gunned him down.

After the moment of silence, junior Khiarica Rasheed read a poem she wrote earlier in the day. Students stopped in the hall to watch as she read the poem that focused on inequity, racism and police brutality.

“Our voice is an instrument, so let’s make it known around.

We are Trayvon. We are Michael. We are Oscar.

The police isn’t the only team. Trust me, we have a full roster.”

Rasheed’s words were followed by various student BSU representatives reading aloud the names of black men killed by the police in the last 20 years. The list included Jonny Gammage in 1995, Amadou Diallo in 1999 and Patrick Dorismond in 2000.

The entire list – including Florida teen Trayvon Martin, who was killed by an armed neighborhood watch member; and Oscar Grant III, a Bay Area man who was fatally shot by a white police officer – had 24 names on it.

“We decided that that is an extreme level of what we’re facing now,” said BSU president and Grant senior Brianna Hayes, referencing Ferguson and institutional racism. “Even while we’re still in school, our black men here –they’re going to have to face this reality. So how can we as a community prevent that and give outlets and empower each other to understand that this is a reality?”

The event was sparked by the recent Ferguson protests in downtown Portland and across the nation over the weekend after a grand jury declined to indict Officer Darren Wilson for a crime in the slaying of the 18-year-old Brown. In Ferguson, riots and looting gutted parts of the Missouri city.

In Portland, nearly 10 people were arrested by the Portland Police Bureau for laying down across the intersection of Southwest Second Avenue and Main Street in a demonstration. Hayes says the events sparked a discussion among Black Student Union members. They wanted to do something that reached the entire student body, not just BSU club members.

“We, as a community, need to work together and change this issue,” said BSU vice president and senior Teresa Patterson. “And not only just African Americans, but everyone. Everyone needs to care.

Although completely student driven, school administrators and staff help the club out when needed. Assistant football and track coach Karl Acker holds a longstanding relationship with the club. He often participates in discussions with the group.

He feels for them and what they are going through. “I facilitate the needs of the students,” said Acker. “But I have no opinion. I don’t want them to follow after me.”

That’s not a problem for Hayes and Patterson, both of whom plan to pursue some level of activism in their lives.

“We need to make change and we need to make it now,” said Patterson, who hopes to pursue restorative justice as a future career. “Not just flipping over cars and burning down buildings – with words. Knowledge is power. That’s what I’m constantly told in my family and that’s what this is about.

“Letting everyone know that we are here to make a change and not with violence. We’re doing something bigger.”

Grant isn’t the only school that’s held demonstrations. Madison, Jefferson and Franklin high schools have held similar peaceful protests with walkouts or moments of silence. Grant Principal Carol Campbell said Wednesday’s event makes her proud to be a part of the Grant community. “It went very well,” she said. “Students of all backgrounds are coming together for a demonstration like this.”

While this is a step in the right direction, Hayes knows that it barely touches what needs to be done to educate the Grant community on race.

“At Grant, we claim that we’re such a diverse community,” she said. But “we’re already underrepresented here at the school in administration.”

Some just don’t see that “people are being shot. Just ‘cause they’re black. And labeled as criminals. Just ‘cause they’re black,” Hayes said. “Our laws are even written against us. Profile. Stop and frisk. That’s why Michael Brown. That’s why Trayvon Martin.”

Hayes tries to look for a positive. “It’s the fear that’s like, I gotta to look at these freshmen that have so much potential – that I see as leaders – that have to face this reality,” she says. “I have to look at my little brothers and say, ‘No matter how hard you work in life to prove yourselves, you might actually have to face – one day – authorities who are supposed to protect you, treat you like you’re a menace to society.”

“We. Aren’t. Talking. About. Racial. Issues. That. Are. Occurring,” added Patterson. “Why is it that we always pinpoint African Americans, you know? Why are we lowering their standards to achieve, but making that gap increase? What are we doing?”

BSU is working to elevate this discussion within the Grant community. “We’re trying to encourage everyone to speak up,” said Patterson.

And yet, Hayes emphasized the fact that too often students think only African Americans can join BSU. That’s not at all the case.

“We’re trying to get at our black students because we see that we’re labeled as underachieving,” she explained. “But also, we want to include anybody who’s interested and anybody who’s willing to feel uncomfortable. Because we feel uncomfortable constantly.”

Hayes said she’d add teachers to the list, too. “Come to BSU,” she challenged teachers and staff. “Sit and understand that your black students aren’t delinquents and you don’t have to discipline them by calling security. Risk feeling uncomfortable. Learn about your students.”

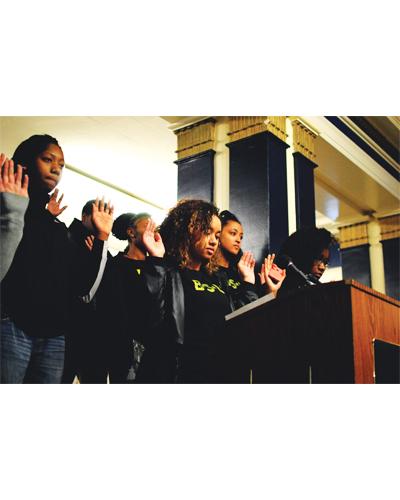

At the end of the event, BSU’s leaders put their hands up in the air. All the students in Center Hall followed suit.

Blu Midyett contributed to this report.