When freshman Millie Williams entered the Grant gym last fall for her first high school dance, she was engulfed in the deep boom of “Down on Me” by Jeremih. Sweaty students were packed into a circle in the center of the dance floor, most of them grinding.

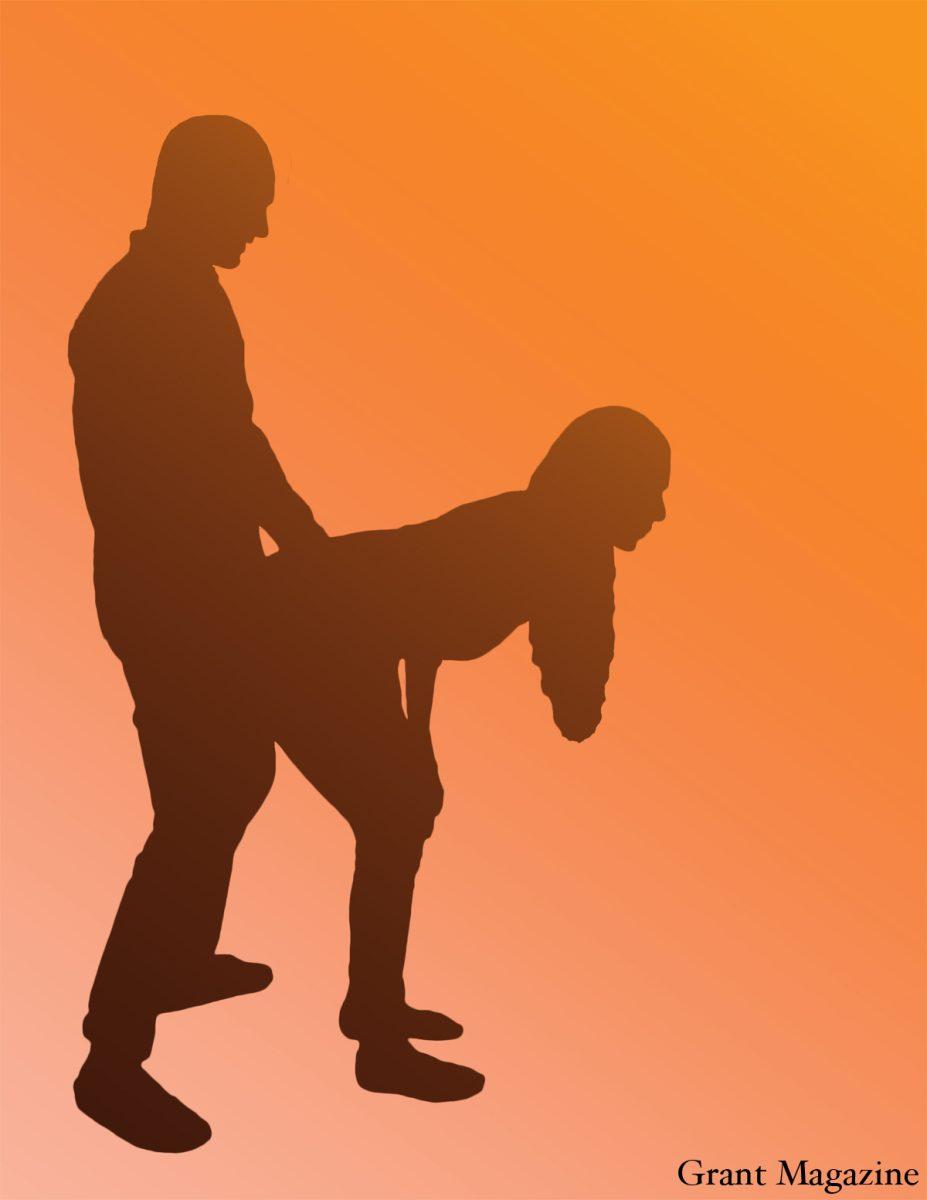

Not familiar with the term grinding? Imagine a bunch of teenagers dry humping in pairs to the beat of loud music.

Williams had heard rumors that the Homecoming dance would be crude, but she ended up having fun anyway. “I think it’s just teenagers being teenagers,” she says. “I spent the whole time just dancing with my friends.”

Principal Carol Campbell, who served as a chaperone, had a very different interpretation of the dance that night. She refers to this year’s Homecoming as a “successful failure.” Drugs and alcohol – two of the biggest issues all schools face whenever a large group of students gathers on a Friday night – weren’t a huge issue.

But the sexually charged dancing was, Campbell felt. She turned the lights on at 10:15 p.m. and ended the dance half an hour early when the grinding persisted. In an administrator’s meeting recap of the event, Campbell wrote: “Sexually explicit dancing and sexually inappropriate behavior was rampant amongst dance attendees. There was little response from students when administration intervened.”

The next school day, Campbell went to Grant’s Leadership Class and presented the students with an ultimatum: Either make the upcoming Winter Formal “cleaner” or school dances for the next four years would be cancelled. Her concerns focused on the culture of Grant dances.

Homecoming, she felt, had devolved into a swirl of disobeying the school’s dress code, violating a number of school policies and dancing in a way more fit for Jersey Shore than a high school dance.

“The only option available for students to partake in during the dance is to either sit on the sidelines or join the mosh pit,” Campbell says. “Students can easily be taken advantage of – especially freshman and sophomore girls who are unaware of their surroundings and succumb to peer pressure.”

One Grant parent who chaperoned at Homecoming says what she saw was a huge problem. “I don’t necessarily think grinding is the issue,” says the parent, who didn’t want to be identified because she worried her child would be targeted for her opinions.

“It is the objectification of girls, it is the anonymity of what the kids are doing to each other, and it is the overly-sexualized nature of it,” she says. “It is pumping, grinding, rhythmic music that never seems to stop – with very disrespectful and suggestive lyrics.”

Sophomore Hayden Rogers doesn’t feel the same way. She transferred to Grant from a small school in southern Washington. She was excited to experience a dance with more kids. “There was like no pressure to grind,” she says. “A lot more people were dancing so I think it encouraged me to dance more.”

Junior Ella Mann thinks grinding is usually consensual. “Of course, you may end up grinding with someone you don’t want to but I think it’s always an option for you to walk away if you feel uncomfortable,” she says.

As Homecoming approached, administrators worried about the potential for students to act out, so they gave a printed list of rules to everyone who bought a ticket. But that did little to combat the problem.

Now Campbell says the administration is going to be stricter about what happens at dances. Under a new policy devised by student leaders and administrators, students will have to sign a code of conduct agreement when buying tickets.

Grant alumnus and special education teacher John Mears, who graduated in 1970, says when he was in high school, students didn’t dance in groups like they do today. “It was always just boy-girl,” he says. “Or sometimes if you were brave, you would kind of just stand there and move by yourself.”

Most boys would shyly stand off to the side, and if they managed to dance with a girl, they didn’t make much physical contact. If two dancers got too close to each other, a chaperone would break them up, he recalls.

In the early 1980s, MTV went on the air and a constant stream of popular music videos was available to anyone with a television. A number of pop artists pushed the limits with videos, clothes and lyrics.

In 1987, “Dirty Dancing” debuted. It was a coming-of-age story where sexually suggestive dance helps the main character come out of her shell. Mears noticed risqué dancing more and more during school dances when he joined the Grant staff the same year. By the 1990s, he says, “It was just kind of like, ‘Yep, that’s how they dance these days.’ Social standards have changed and become more lenient.”

At this year’s Homecoming dance, many students – like freshman Finn Hawley-Blue – felt pressured. “Coming from da Vinci, we didn’t have that kind of dance,” says Hawley-Blue, who only went to the dance because he was required to attend as a member of student government. “For the people that don’t want to go into the mosh pit, it’s not a comfortable thing to do.”

Freshman Mayumi Head didn’t enjoy the dance either. “It was just uncomfortable. People were just coming up from behind me and I didn’t know what to do,” she says.

Sophomore Emma Palin opposes dirty dancing, but doesn’t want dances to change. “Grant’s social scene is not thriving at sports events or theater,” she says. “The dances are usually where people all come together. I don’t know if that many people will want to go anymore with these new rules.”

This year, Grant sold about 700 Homecoming tickets, raising about $4,000. The new guidelines will come into play with this year’s 1920s themed Winter Formal on Feb. 14. The event is set to be held at the Bossanova Ballroom on East Burnside Street instead of the school gym.

Student leaders and the administration decided to shift the event half an hour earlier than other dances. There will be more varied music and activities designed to prevent sexually suggestive behavior by giving students options other than dancing in the crowd. ♦