The blare of the buzzer echoes around the Grant High School gym and the crowd’s intensity gradually dampens. The Grant women’s varsity basketball team just lost to Sheldon, 77-46, a team that beat them by 29 points a month earlier.

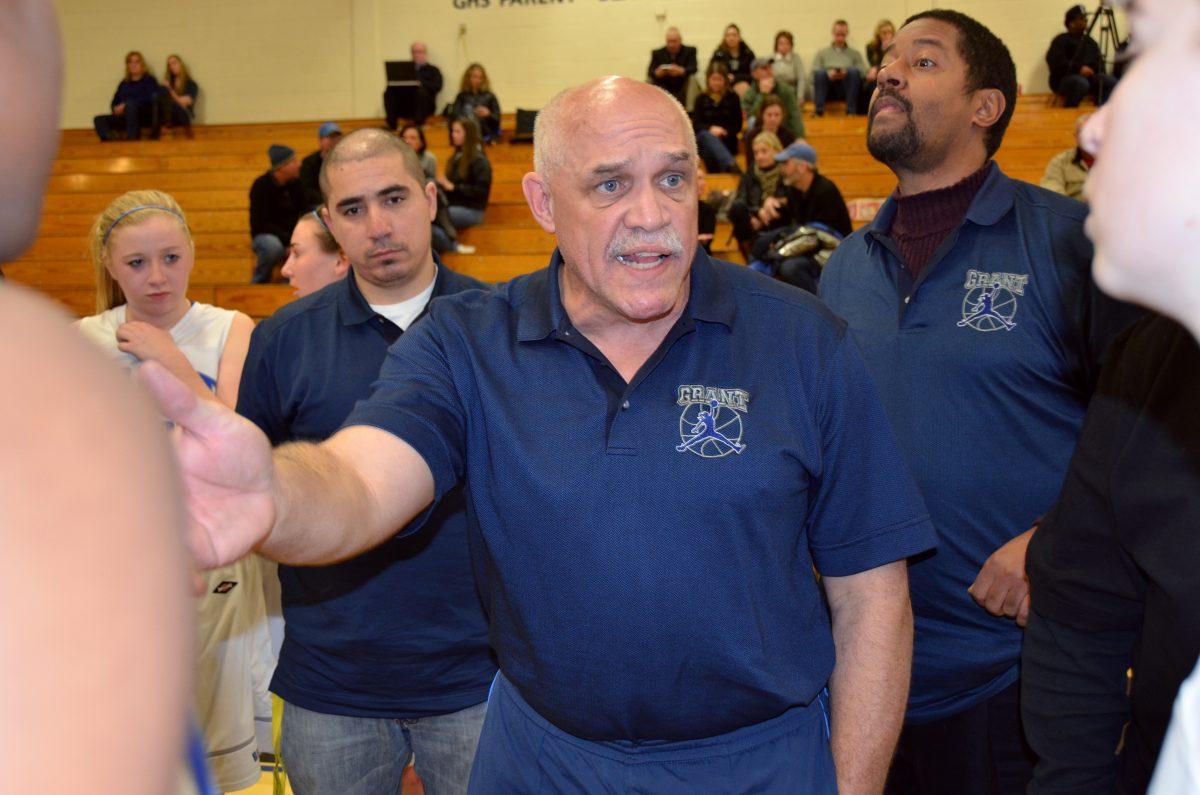

Coach Michael Bontemps, in his first year at the school, finishes talking with his players and emerges from the locker room.

He pulls one of his senior captains aside. Displaying what many consider his “tough love” coaching style, he converses with her for nearly 30 minutes, addressing a need for improvement in leadership and work ethic. “We lost our ability to fight,” he tells her, “I’m looking for someone who wants to fight.”

Bontemps took this coaching position one year ago, well aware that he was entering a program in shambles. However, with a state championship and nearly 40 years of coaching under his belt, he is excited and motivated to push the Grant girls forward.

He’s proven on multiple occasions that he’s capable of building a successful women’s program from the ground up. At Jefferson, he started with young talent and within a couple of years led his girls to an undefeated state championship season.

“Portland girls basketball is really crumby across the board,” Bontemps says. “I don’t think coaches work hard enough building programs.”

After a season that “blew up” last year, Principal Vivian Orlen scurried for a replacement. “The program needed a solid adult to lead,” Orlen says. “Bontemps seemed like he could do it blindfolded.”

Orlen is proud with her decision because the coach she picked “lives and breathes Grant women’s basketball.”

Bontemps says he wouldn’t have it any other way.

“This time of year, I’m in the gym seven days a week,” says Bontemps, who recently retired from teaching social studies at Parkrose High School. “I want parents to see someone who is willing to help their kids improve not just in basketball but all the way through. I see my mission as helping kids grow.”

Bontemps was born in 1954 to African American parents in a predominantly black neighborhood in Chicago. But Bontemps was a rarity: blue eyes, fair hair and light skin. He says he was known as “the white boy on the block”.

Bontemps embraced the difference. “I strove to be different from everyone else,” he says. “I was always pushing back on the stereotypes.”

Although he says it’s never been a big deal, his racial identity has generated conversations “that need correcting,” he laughs.

When Bontemps was about 10 years old, his family moved to Illinois. A passionate athlete, Bontemps ran track and played football in high school but wasn’t able to make the basketball team.

He maintained his love for basketball because he was a “gym rat” and often watched his friends practice from the bleachers.

Bontemps improved his grades during his junior and senior year, graduating with a GPA over 3.5. While football was his passion, his life was far from average potential college athlete. By the time he was in a position to go to college, he had a wife and a son.

He and his now-wife met when Bontemps was a junior in high school during a study hall. When she became pregnant, Bontemps was forced to make a major decision. “That was a defining moment,” he recalls, having thought about becoming an electrician. “Do I go to college or do I get a job and support this kid?”

Bontemps didn’t get to make the choice – fate made it for him. He failed the diagram portion of the electrician’s test and said to himself: “To hell with that. I’ll just go to college.”

He attended Illinois Benedictine University on a football scholarship as a defensive back. While in school, he worked for United Parcel Service, waking up as early as 3 a.m. to get to work. Then he went to class and then to practice. He maintained the regimen through college and finished in four years.

About 10 years after graduating college, he ran into his old head coach. “I remember him saying, ‘I saw you walk in and I thought I would only have you for a year. I was disappointed you’d be gone,’” recalls Bontemps.

After college, an old teacher from high school called him, offering a teaching job in Arizona at a wealthy private school. Bontemps said it was his first experience “on the other side.” One of his students was a senator’s daughter who lived in a massive gated community. “It opened my eyes,” Bontemps says now.

After a year in Arizona and a rough winter back in Illinois where “my car was never working,” Bontemps moved further west and settled in San Diego. He wasn’t able to find a teaching job, so he resorted to a job in construction.

Two years in construction was more than enough, and after witnessing his peers suffer injuries that put them out of work, Bontemps needed a change.

In the late 1970s, his father was relocated and moved his entire family to Oregon for work. Bontemps figured it would best to join him there, so he packed up his wife and two children to move to Portland. They settled on Northeast Alberta Street.

Bontemps got a job at the then-Washington Monroe High School, which was an all-girls school. He taught social studies and coached girls basketball. The job only lasted one year, but his career with Portland Public Schools was far from over. When Washington Monroe closed after his first year teaching, he was relocated to Benson.

It was the first year the school admitted women and Bontemps was struck by the amount of social inequity demonstrated by his peers. “I was learning about Portland,” he says. “It seemed to be stuck in the past, but not in a good place.”

Bontemps advocated that the new girls basketball program should have as much access and attention as the boys. But administrators “weren’t interested in that mentality. They did the right thing and didn’t hire me as coach,” he says.

Bontemps advocated that the new girls basketball program should have as much access and attention as the boys. But administrators “weren’t interested in that mentality. They did the right thing and didn’t hire me as coach,” he says.

About the same time, Bontemps’ older brother, who was still living in Illinois at the time, got into a confrontation on New Year’s Eve with his ex-wife and her husband. There was a shotgun involved and by the end of the night, his brother was dead. He wasn’t close with his brother. “He was a bully,” Bontemps says.

A month later, Bontemps’ father died of a heart attack. “That was harder to deal with,” he recalls.

After the deaths, Bontemps developed a new insight on the value of family relationships. “I tried to make it so my sons were friends,” says Bontemps, who adopted his nephew after his brother’s death. “My nephew came and we helped raise him. He was the fourth component to the Bontemps Boys.”

To this day, Bontemps still holds his family close.

“l try to do something with us as a group all together. Every summer we go somewhere,” he says, pointing to recent trips to Hawaii, Mexico and the Bahamas.

Bontemps bounced between schools including Lincoln, Franklin, and Madison, teaching and coaching football and basketball along the way. He still uses the lessons from the classroom and the court today. He says he learned to read his students’ needs and to “value individual effort.”

He coached girls JV basketball for a stretch at Jefferson before moving to Parkrose. In 2004, he landed the head varsity coaching job at Jefferson. The next year, a group of freshman girls showed up at his tryouts. All of them were quite skilled and he saw major potential.

Their sophomore season, they scored 100 points in a game more than nine times. But the team was disappointed when it lost in the semifinals and placed third in state.

The next season, another strong crop of freshmen tried out and by 2008 things were looking good. That year, he led his strong junior class and precocious freshmen to a state championship, beating Hermiston High School in the finals.

“It was a relief. We were supposed to (win) the year before but we got burned,” says Bontemps. “We finally did it. It paid off. I got to see a group that I started out as freshmen mature and succeed as people and as athletes.”

After that victory, he decided to quit coaching at Jefferson due to issues with administration. When Bontemps left Jefferson he told himself he was done coaching. “I missed being in the gym,” he says.

When the Grant position opened, he applied. “I saw a lot of potential at Grant,” Bontemps says.

He wants to change the school’s attitude toward girls basketball and improve participation, something that he has already proven with numbers. Last year, only 22 girls showed up to play basketball. This year, there are 30.

“Here at Grant, I literally started with seven girls who had never played basketball,” he says. “The rest of my group are freshmen that I convinced to come out and play.”

He wants to build a youth program, getting kids involved at the elementary school level. “Girls don’t get a chance to play basketball like boys do,” Bontemps says. “I have a goal to get to know youth players and give them an opportunity to experience basketball.”

Senior Myleah Musgrave says Bontemps brings order compared to last season. She says her previous coach had trouble motivating players and didn’t hold everyone to the same standards, remembering the time that a player was benched for an entire game because of attitude while another teammate was benched for a half because of an alcohol incident.

This year, “Bontemps has already established a relationship with his players,” Musgrave says.

Senior Caylee Newsom agrees the coaching change has brought out more heart and less drama with her team. “He encourages everyone to put in effort every day,” Newsom says.

Assistant coach Andrew Hawkins says it comes down to Bontemps’ desire to win. “He wants his players to win, and not just on the court,” Hawkins says.

Even with two freshman starters and many others on his varsity roster, halfway through the season he’s already coaching his team to be better than last year.

“Kids have some many different ways they can go,” he says. “If I can help them in the right direction, I have created value. I wouldn’t change it for the world.”