When Kristyn Westphal was 12, she withdrew $100 from her personal savings and anonymously sent the money to a family she knew was struggling. She’d saved up the money from her allowance and babysitting. No one told her to do it, nor was there a fundraiser.

“I just wanted to help out,” she recalls.

Westphal doesn’t like to say that she helps people. Instead, her goal is to support people as they learn how to help themselves.

In her own words, Westphal wants to be a resource.

Ask her mother, Elinor, about her oldest daughter and she’ll tell you: “She has a generous spirit and she hurts when other people are hurting.”

Father Ken agrees. “She has always had a soft heart,” he says.

Kristyn Westphal, 33, takes over this year as Grant’s new vice principal of curriculum and instruction. She replaces Brian Chatard, who spent nine years at Grant. He has moved on to become the principal of Wilson High School in Southwest Portland.

Westphal is relatively new to education in Oregon. She spent four years at suburban Newberg High School as an English teacher before coming to the Portland Public School District as an administrator last year.

Grant Principal Vivian Orlen began searching for candidates for Chatard’s job in late June. She contacted Westphal after hearing recommendations from several colleagues, and they spent three hours talking at a coffee house. “My sense was there were things that Kristyn would be really good at that would strengthen the leadership team,” Orlen says.

“She really sees education as opening doors for young people. She’s super organized. She has a really strong work ethic. I think she can have a really positive impact on faculty and students. I feel really lucky to have her on the team.”

Westphal says she wants everyone to know her message to Grant is simple: she is approachable and available. “If people need something – or even if they don’t need something.” She adds, “I want people to feel comfortable talking to me if they need to talk about something.”

Westphal’s childhood takes a page out of an idyllic Midwest novel. She grew up in Overland Park, Kansas, a suburb half an hour south of Kansas City. The oldest of three children, she remembers having the freedom to play outside all day without supervision.

Every week, she and her sister, Rachel, and her brother, Kyle, received six quarters to be traded in for 30 minutes of television for each coin. The three would save up their money for Saturday mornings, when they watched Star Wars and 1960s Batman reruns.

There was always music playing in the Westphal house – with a mix of records ranging from Vivaldi to Billy Joel to Chicago. Sometimes, Westphal would sing show tunes while her mother, a stay-at-home mom, played the piano.

“She had a beautiful voice,” her mother says, remembering a Christmas pageant in which a three-year-old Westphal performed “When God Became A Baby”.

Today, her father admits that he misses her singing around the house. Ken Westphal worked as a freelance illustrator who would play along with his daughters by pretending to be an art director assigning them artwork. The girls had fun with the drawing game; their father enjoyed taking breaks from work to spend time with them. “It was just a natural part of our day,” he says.

Westphal was an early and voracious reader. P.D. Eastman’s Go Dogs Go was the first book she read by herself when she was 4. Her father first read her J.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings when she was 7. She recalls how he would make up voices for every character and skip any long, boring parts.

Her sister recalls Kristyn reading Beverly Cleary’s Ramona the Pest books to her when they were both young.

Westphal spent a lot of time browsing the fiction shelves in the library, searching for novels like The Babysitter’s Club. She began reading classics in middle school, and tackled the 1,400-plus pages of Les Miserables in her freshman year of high school.

She also had a lively imagination. Her father remembers Westphal trotting through the house like a horse, not hearing a word anyone was saying. Westphal and her sister spent afternoons playing with the other kids on their block. Her best friend was Tara Bonin, whom Westphal’s known since they were four.

Westphal’s elementary school education was a sporadic mixture of public, private, and homeschooling. She spent fifth grade through seventh grade being homeschooled by her mother, which was challenging because she was a very social person. Westphal then skipped eighth grade, going straight to ninth grade public school.

Much of Westphal’s childhood was spent over at Bonin’s house on the jungle gym. As they grew older, the talk turned to boys. Westphal admits she had many crushes – like Ralph Macchio in The Karate Kid. Then there was her father’s 20-year-old art student who was married.

Westphal and Bonin drifted apart during high school, a period that Westphal remembers as often being lonely. “I would have liked to fit in more,” she remembers of her high school days.

Not long into her freshman year, Westphal’s geography teacher recommended she switch to the honors class. Because of this, she took honors courses for the rest of her time at high school. Today, this stands out to her as an example of how important a single teacher can be to a student.

When she wasn’t studying, Westphal performed as walk-on scenery in school plays and sang in the choir. After high school, she attended the University of Kansas on a full-ride scholarship as a National Merit Scholarship finalist.

As a freshman, she signed up for a Native American literature class taught by professor Bud Hirsch. On the first day, Hirsch told her he was concerned because it was a senior-level class. Westphal remained and earned an A. They became friends and Hirsch proved to be an inspiration to her because he was passionate and went out of his way to help his students improve. It was partly due to Hirsch’s advice later that Westphal attended graduate school.

One day walking on campus, Westphal saw her old friend Bonin and discovered she was attending the same university. They became good friends again and Westphal still considers Bonin her best friend, though she’s really like another sister.

In 2001, she graduated from Kansas with an undergraduate degree in fiction writing and literature. She was working in retail to make money when a friend told her about a service program. Westphal began several unpaid internships working with homeless teens. She served food, worked in outreach programs, and listened to the homeless tell their stories.

She had an intern experience in San Francisco where she enjoyed working with young adults. Once, she and three other interns spent five days and nights “spare-changing” in Golden Gate Park. “It was to experience what it’s like to be homeless in a very small way,” she recalls.

After a while, Westphal realized the work didn’t quite fit her. Something was missing.

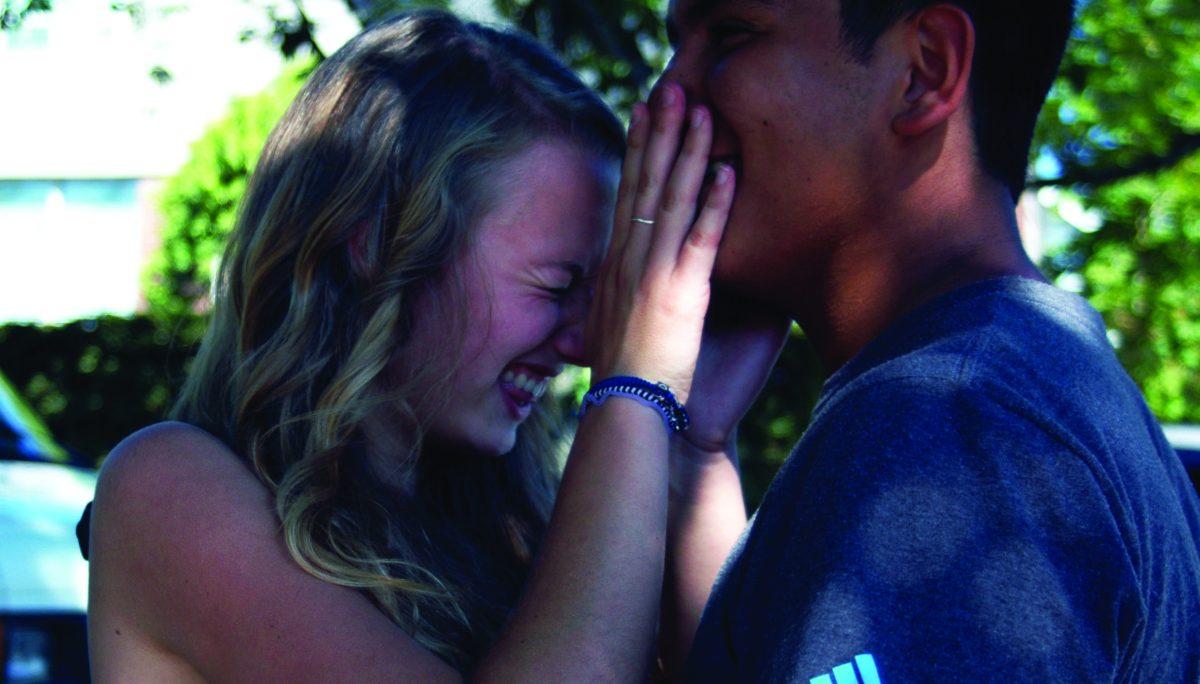

In October 2003, she moved to New York City, working in an upscale grocery store. A few days after she moved, Westphal was invited by a friend to Yom Kippur services, a holiday celebrated as a day of atonement for Jewish people. The woman had also invited another friend named Elvyss Argueta.

Argueta’s parents came to America from El Salvador before his birth and he grew up in South Central Los Angeles. He came to the service because he was somewhat interested in the woman who had invited him. After the service, he asked the woman to lunch but she told him she couldn’t make it. He turned and asked Westphal.

She said yes, but later cancelled due to work. She suggested dinner at a café instead. It wasn’t clear if it was a date or not, but they hit it off. Eventually, they started dating. “There was something that clicked,” Westphal says now.

She said yes, but later cancelled due to work. She suggested dinner at a café instead. It wasn’t clear if it was a date or not, but they hit it off. Eventually, they started dating. “There was something that clicked,” Westphal says now.

A year later, she left for Oxford University in England. She was thinking of becoming a professor of literature and planned to get her graduate degree in English. The couple stayed in touch using Skype and had occasional visits, and she finished the compressed program by 2005. Westphal recalls that her time at Oxford felt too unrelated to the real world. She lost interest in being a professor because she wanted to make a more direct impact on society.

In 2005, Argueta suggested that she apply to Teach for America, a program that trains teachers to provide educational opportunities for low-income communities. She was accepted and spent six weeks in an intensive training camp. Likening the experience to an army boot camp, Westphal worked nearly around the clock. She learned a lot about equity and opportunity while teaching Dominican students as part of the training. She discovered a lot about her own racial identity and the privilege she had growing up.

She was a successful student in school partly because her parents and teachers told her that she could be. She wanted to support students who didn’t have the support she’d had growing up, as well as those who had help. “I really like working with students at both ends of the spectrum,” Westphal explains.

After completing the program, Westphal worked at a middle school in Manhattan, teaching seventh-grade language arts. Her first year was a horrible experience. “I cried every day,” she recalls.

She’d always been good at things and she wasn’t used to doing something that didn’t come naturally. But at the end of the year, Westphal thought back on what had worked and what hadn’t, determined to try again.

She taught eighth grade her second year, partnering with a special education teacher who helped with a few special needs students in her class. Westphal had been frustrated in her first year when students wouldn’t pay attention. But she began to find ways to get students involved.

Today, nothing bothers her more than when she sees a student with his or her head down and the teacher ignores it. She recognizes it can be difficult to engage every student, especially in large classes. But teachers have to always try. “You never give up,” she says adamantly. “You try to be effective with every student.”

By the end of her second year teaching, Westphal was ready for a change. She and Argueta decided to move to Portland where they could enjoy the outdoors together and be closer to family living on the West Coast.

They talked about marriage and went as far as ordering a wedding ring for Westphal. While watching TV and eating potato chips, Argueta talked about when he should propose. Then he asked her. She was a bit thrown off and said he should at least turn off the TV and put down the chips. She was a little disappointed that it hadn’t been a bigger deal, but she made her peace with it and said yes. They got married at City Hall in a small ceremony in July 2007.

That fall, she started a new job teaching at Newberg. She enjoyed teaching high school students much better than middle school because she was able to teach more complex ideas. At Newberg, Westphal taught English, support classes and even designed her own dual-credit program.

Her goal was not only to teach students to love reading and learning, but also to show them how to express themselves with confidence. “The teacher’s job is to help students learn to help themselves,” she says now. “I really think that people have the answer to their own problems.”

She decided to leave teaching and move on to administration so she could have a different kind of influence on the lives of students. Once she received her administration license, Westphal left Newberg – a tough decision because she was so close to her students. Some of them still write her letters from college.

“I loved teaching,” Westphal says. “But I’m really excited about what I’m doing as an administrator.”

At Portland Public Schools, she took on the challenge as sole administrator of the Evening Scholar’s program in the fall of 2011. Then she led the Portland Summer Scholar’s program this year. These credit recovery programs amassed 1,400 students per session at Benson High School. With teachers and students constantly shifting in and out with each session, Westphal felt she was unable to create many lasting relationships.

When Chatard announced he was leaving for Wilson, Orlen contacted Westphal about the job opening. Only a couple weeks later, she had a new job. Over the summer, Westphal worked to transition into her new position, meeting with staff and “poking around” the school itself. “I’m a very visual person,” she explains. “And I’m also notoriously terrible with directions.”

Westphal was gleeful to discover big windows in her office that let in the sunlight she desperately craves. She has decorated with framed certificates on one wall and pictures of friends and family on another. She has a library of books within easy reach for sharing and framed pictures of Gandhi and Malcolm X lean against a wall. Her filing cabinet is adorned with Star Wars magnets.

A naturally social person, Westphal hopes to meet as many people as she can within the Grant community. She plans to spend as much time as possible within the classroom, something she strove to do in her previous job as an administrator.

She also wants to help unite the school within itself because, she explains, teachers are most effective when they’re working together. “Teachers are the most important factor in students’ success,” she declares. “Second to that is a good administrator.”

Her sister, Rachel Guthrie, believes that Westphal better understands students’ tough times in high school because of her own experience as a kid. “If you need something you can go to her and ask for help,” she says.

When she isn’t meeting with students, Westphal enjoys being outdoors. She went on a trip with her sister to Yosemite National Park over the summer. Her sister lives in Seattle, which is fairly close, but Westphal only sees her parents and brother a couple times a year. Westphal always thought Kansas would be home to her, but now she says: “I consider myself an Oregonian.”

Westphal and Argueta watch movies together, though Westphal reveals they often have to compromise. “He’s into chick flicks,” she laughs. “I’m more into dramas.”

Westphal wants to have biological children someday, as well as adopt. She plans to raise her children as bilingual, speaking English and Spanish, which is Argueta’s family’s native language.

Argueta believes his wife’s new position at Grant will turn out well. “I think that students and teachers will benefit from her experience,” he says.