It was 1987. When Ahmed Kelso walked up the path to his father’s home in Panama, a painful pocket of anticipation pounded in his chest. He was aware that his life would change in the next few moments, but he knew it was time.

“I was very nervous, but I was going to leave Panama,” Kelso recalls. “I had to tell my parents the reason.”

“It wasn’t pretty,” he says, looking back to the day he first came out to his mother and father. He was 30 at the time, but he still remembers the “hysteria, screams, and blaming” that erupted.

He always knew this would be the reaction he’d have to face one day, but that awareness could only absorb so much pain. He felt torn, and several years passed before his mother accepted him again. Nineteen would pass before his father would treat him normally.

“I think that’s what a lot of gay people are most afraid of,” says Kelso. “The thing we fear most is the rejection of family and friends.”

Kelso is currently a Spanish teacher at Grant and he loves his job. But his life is very different now from what he imagined when he was younger. He got a law degree at age 24 and then worked as a lawyer for nearly seven years. Between the fallout with his parents, meeting the love of his life, and the harsh dictatorship and acceptance issues in Panama around gay people, it was time for something new.

“At the worst of the dictatorship, there was a fear: many telephones were tapped and you couldn’t express your opinions in public because there were informants everywhere. I wasn’t happy,” he recalls. “I didn’t want to live in a society in which I had to pretend.”

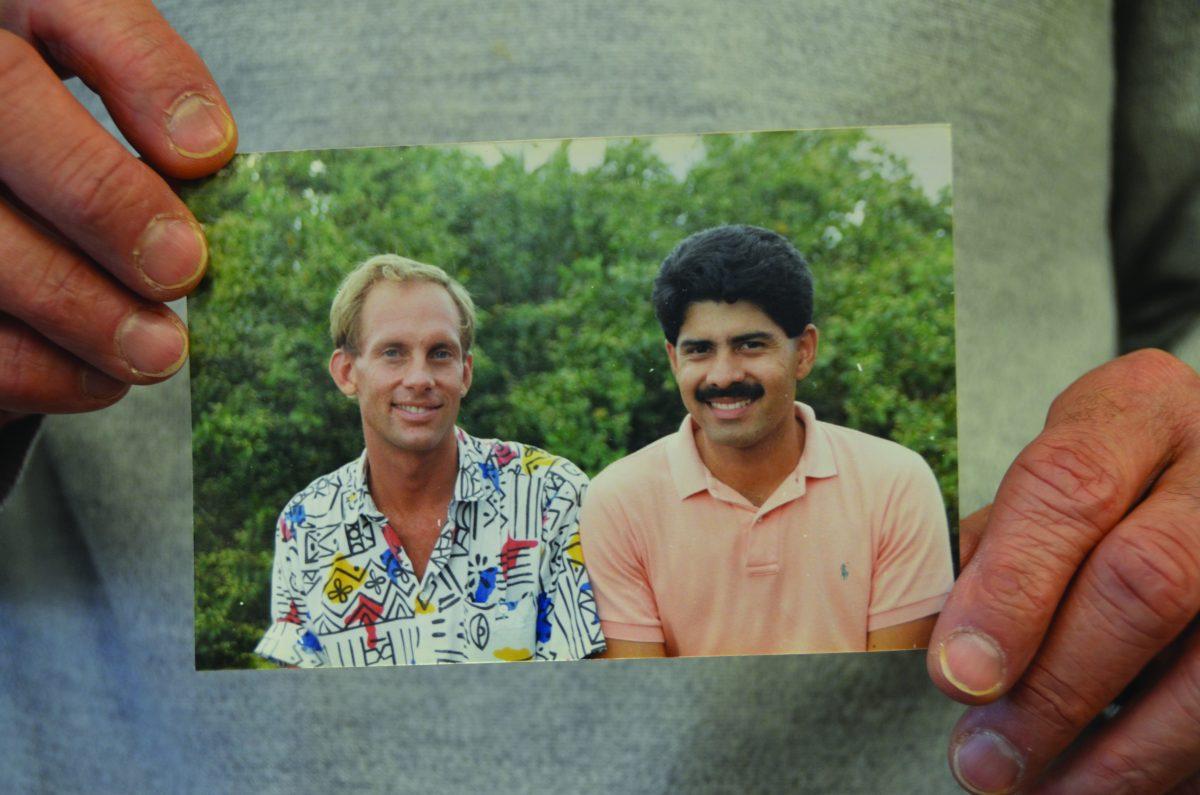

Meeting Allen Koshewa, his current partner of 25 years, made Kelso’s decision to begin a journey and leave his old life behind much easier. Less than a year after meeting, Kelso and Koshewa decided to kick off their relationship by spending a year travelling the world together.

Meeting Allen Koshewa, his current partner of 25 years, made Kelso’s decision to begin a journey and leave his old life behind much easier. Less than a year after meeting, Kelso and Koshewa decided to kick off their relationship by spending a year travelling the world together.

“I made the choice to leave Panama with him. I wanted something different,” Kelso remembers. “I wanted to grow as a person, and Panama wasn’t letting me grow. I wanted to explore other things and other possibilities in life.”

Born and raised in Panama City, Kelso grew up alongside three sisters and an older brother. He has many fond memories of his early childhood, including spending time on his family’s cattle ranch near the ocean. “We used to visit our cousins and have so much fun,” recalls Kelso’s sister, Querube Kelso. “We would ride horses, go to the beach, play with farm animals” and much more, she says.

The days flew by as he spent time with his siblings and cousins. But there was another side to his life, one of fear.

“I was bullied all my life,” Kelso recalls. “First grade to tenth grade, it was awful. I was always scared to go to school. It wasn’t only the kids: some teachers were very verbally abusive.”

Kelso remembers his mother going to the school on multiple occasions, but the faculty didn’t seem to care – they left it up to him. “I had to do what my parents and teachers ordered, not asked me, ordered me to do,” says Kelso. “I grew up in a world in which the voice of young people was not taken seriously at all.”

Kelso’s first experience in the United States came at age 13, when his father sent him to a military academy in Pennsylvania so he could improve his English. He had studied English since early elementary school but that year of immersion, during which he slept in barracks, was what helped him become comfortable with the language. Though he learned a lot during his time in Pennsylvania, young Kelso decided he was ready to return home to Panama after a year.

“I missed my family,” he remembers.

Kelso finished his high school education at an all-boys Catholic school back in Panama, then went on to study law at Panama City University.“ I really enjoyed practicing law,” he recalls, but after reaching his early 30s, other options presented themselves. It became clear that his law career would be short lived.

“The exact day? May 2, 1987,” Kelso quickly responds when asked about the day he first met his partner. Koshewa was born in Texas and brought up in Atlanta, Georgia.

“I realized he wasn’t Panamanian,” Kelso recalls. “I wondered if he spoke English and I wanted to practice.”

They met at a public swimming pool when Koshewa was a Fulbright lecturer at the University of Panama, educating future teachers of English.

Around this time, Kelso was active in politics and often attended demonstrations against the military dictator, Manuel Noriega. During one protest, Kelso was captured and imprisoned for several hours, during which he endured moderate forms of torture and humiliation.

“I didn’t know what happened – he just didn’t come home,” says Koshewa. “I knew something had happened, but this was before there were cell phones.”

Fortunately, Kelso was allowed to return home later that night. He was shaken and sore, but not discouraged. “He continued protesting against the military dictatorship because he is a man of convictions,” says Querube Kelso.

Kelso and Koshewa grew fond of each other shortly after meeting, but to Kelso’s family, they first presented themselves as “just friends.” Koshewa grew very close to Kelso’s entire family.

“I actually got to know him at first,” Koshewa says of Kelso’s father. “But he just thought I was a friend. When we actually decided to go abroad together and Ahmed said, ‘Oh he’s my partner,’ that changed.”

This is when things got out of hand and the family dynamic changed.

“It was really hard. We couldn’t all be together as a family for many years,” says Koshewa. “Everyone would go over to his sister’s or we’d go out and his dad just wouldn’t come.”

Querube Kelso remembers the challenging and emotional time as if it were yesterday.

“My priority was Ahmed’s well being and happiness; above all I concentrated in giving my brother my love and moral support as best as I knew,” she says. “I wanted to be there for him.”

Nineteen years after the conflict arose, Kelso’s father invited Koshewa over on Christmas Eve. He gave Koshewa a present and acted as if nothing had happened.

“Now I have some of my best conversations with him,” Koshewa says. “It was pretty encouraging because it shows that people have the capacity to change. He was already in his 80s when he decided to accept me, and now it’s really normal. I love going there.”

Kelso will never understand what went through his father’s mind to engender that change, but he’s very grateful that he and his partner receive a warm welcome when they take their annual trip to Panama.

“That’s a mystery to me, all of a sudden it just happened overnight,” Kelso says, “But time heals and helps think things over. Now they are accepting.”

But with or without his parents’ acceptance, Kelso has always been comfortable with himself and his sexuality. “I’ve known all my life, since I can recall,” Kelso says. “You’re born that way.”

After coming out to Kelso’s parents, the couple began their trip around the world. They explored the United States, then went on to Europe, Morocco, Nepal, India, Thailand, China, and Japan, often spending extra time in places they enjoyed most.

Unfortunately, their journey came to an end with the expiration of Kelso’s cultural visa, which forced him to return to Panama. At this point he had to decide what to do. Because the court system in the United States is different from that of Panama, Kelso found that he’d have to go through law school all over again to remain a lawyer, but he felt he was a bit too old.

Kelso remained positive and realized that a lot of good could come from teaching Spanish, which he had dabbled in and enjoyed in the past.

“I wanted to do something that meant a lot to me, something that I could practice anywhere in the world, and that would provide me with means” to live, says Kelso.

Kelso acquired a student visa as quickly as possible so he could join Koshewa at Indiana University. The couple lived together in Indiana while Kelso was getting his master’s in teaching and Koshewa his PhD. Koshewa remembers the constant pressure they felt due to their visa situation.

“What’s interesting is that for the first 17 years of our relationship, we never knew if we were going to be able to stay together,” says Koshewa.

After graduating, Kelso taught briefly in Indiana before the couple set their sights on Portland.

“When I was teaching in Indiana, I felt at some point that we needed to move on,” he recalls. “I felt that Portland was the ideal place because it’s a progressive area. I won’t say the whole Oregon, but at least Portland.”

After arriving in Portland, Kelso found his first job at Wood Middle School in Wilsonville, where he spent a few years teaching Spanish. It wasn’t until 2002 that he landed the job at Grant, where he has enjoyed teaching ever since.

During his early years teaching in the United States, Kelso was on a work visa that needed to be renewed once every five years, a tedious task. In 2007, he decided he was ready to be done with the hassle of renewing visas. Aware that friend and colleague Dr. Christian Dreyer, an English teacher at Grant, had been through the American citizenship process himself, Kelso knew exactly where to turn. “I asked him where I could find the forms, and he pulled them up for me on his computer,” Kelso recalls. “In a matter of six months, I got citizenship. It was very fast.”

Today, Kelso’s life follows a simple arc: he loves his family, he loves his life, and he loves his job.

“Teaching is part of a bigger thing,” Kelso says. “My main interests are to keep growing as a person and as a teacher. This growth involves getting to know people: that’s my main thing in life, getting to know other people.”

People around him say Kelso stands out because he is a great friend and a great teacher. “You meet certain people and there’s something about them. There’s some kind of little spark that you’re drawn to and you become friends,” says Ron Crossier, a retired teacher who met Kelso while he was applying to PPS. “He has that.”

Koshewa couldn’t agree more. “He’s very, very sincere and humble,” he says of his partner. “He plays violin but he never wants to play in front of other people because he doesn’t feel like he’s good enough. He doesn’t like to toot his own horn.”

Kelso’s sister agrees. “He is the best friend, brother, mate, that anybody would like to have and I am honored to be his sister,” says Querube Kelso. “He is my confidant and I seek his advice because I trust him deeply.”

Aside from playing the violin, Kelso enjoys reading a wide variety of books and magazines, hiking, and camping in various places around Oregon. But what Kelso looks forward to most are the trips he takes with Koshewa. “We travel overseas every summer,” says Kelso.

Each year the couple leaves the country, travelling to places like India, Mexico, Thailand, Japan, the Republic of Georgia and Armenia. They also visit Panama once a year to visit family. “My partner and I go together, and they are very kind and warm to us,” says Kelso.

Although he participated in gay rights demonstrations when he was younger, Kelso is now very content with his life and relationship with his family, and thus he channels his energy in other directions.

“I am not an activist but I support it in another capacity. For example, giving money to various organizations,” he says. “It all changes, and I have other priorities now.”

Kelso spent many years as the adviser for Grant’s Gay Straight Alliance club but gave up the position at the end of last year.

“As you get older you get more mature,” says Kelso. “You get more secure, you feel more in the capacity to stand for what you are.”

Now happy as could be with their domestic partnership, Kelso and Koshewa don’t feel the need to get married.

“What kept us together is that we understand that any good relationship takes a lot of work,” Kelso says. “I don’t feel that a piece of paper is going to make a difference after almost 26 years.”