DISCLAIMER: Please keep in mind that all student feedback was collected from a student-made form. Some questions and sample sizes differed across surveys. Although an attempt to capture the student body’s opinion on each grading policy, data may be skewed and should not be used for professional means or to compare teachers to each other. Additionally, some teachers requested not to have forms sent out to students and some forms did not receive enough responses to be posted. All visuals were created using Google Forms.

Teacher: Amy Polzin (she/her)

Classes taught: Biology, Physics & Algebra Workshop

Years taught at Grant: 10

Grading policy and philosophy (Biology Only):

Amy Polzin uses a four-point proficiency scale for her biology classes. Her system is constructed so that at the top of the proficiency spectrum, a grade in the range of 3.5-4 points equates to an A. Meanwhile, at the bottom of the spectrum, anything from 0 to 1 is an F. Polzin distributes the assignments into two categories: summative and formative. Summative assignments account for 70% of the grade, and formative assignments make up 30%.

Polzin says it is relatively straightforward to earn a passing grade in her class as long as students are showing up and participating. “I didn’t want it to be (so) challenging that people didn’t feel like if they were attending and attempting work they wouldn’t pass the class, because it’s a required class for everybody,” she says.

Polzin is likely to round up to the nearest decimal place. Her usage of proficiency can make this challenging, however, because Polzin has to remind her students that it is different from a points-based grading system and there is less room to round up.

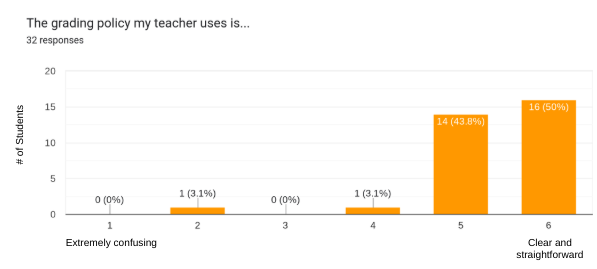

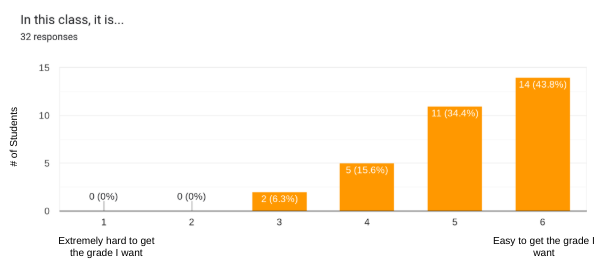

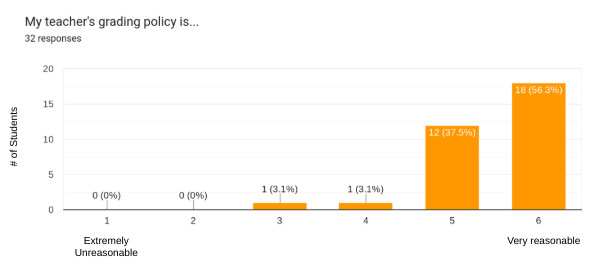

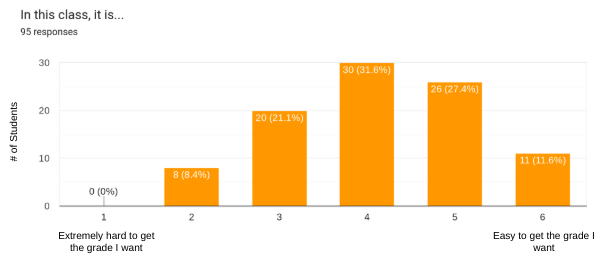

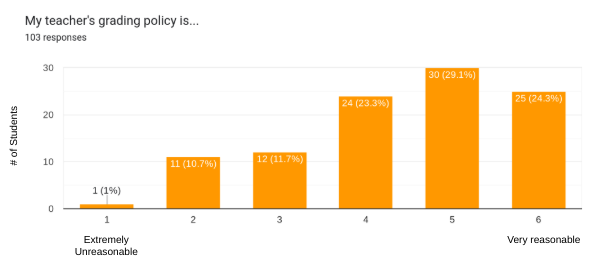

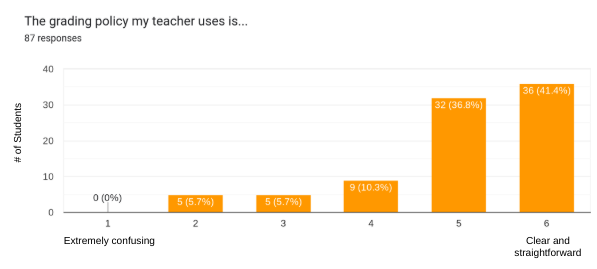

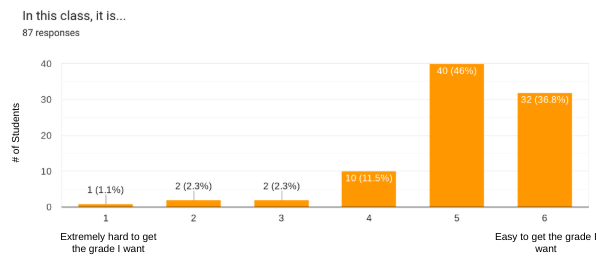

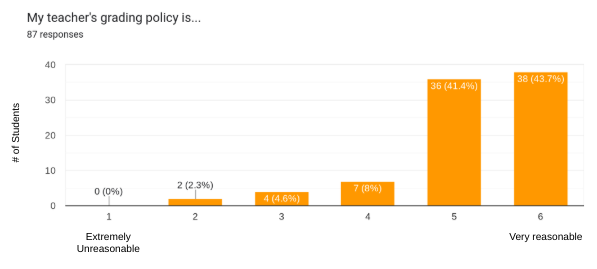

Student Feedback:

Teacher: Bill Wilson (he/him)

Classes taught: Chemistry & AP Chemistry

Years taught at Grant: 18

Grading Policy and Philosophy (AP Chemistry Only):

Bill Wilson tries to make his AP Chemistry class similar to a college-level course by heavily weighing exams at 70% of the grade, while other assignments — such as labs and homework — make up the remaining 30%. Wilson says he weighs non-exam assignments because “it’s a recognition that there’s importance to trying, and showing some understanding in the practice format.” Wilson believes that having a class that mimics college courses will better prepare students who decide to attend college.

Wilson rounds grades up to the nearest whole percentage, because he acknowledges that teachers can be imperfect, and believes the rounding will help account for possible margins of error that occur in the grading and teaching process. In Wilson’s class, if a student scores a three or higher on the AP Chemistry test, he will change their grade from both semesters to an A. Wilson says, “I think it’s a nod to this high stakes test … where … you can show a level of understanding that gets you college credit. From a method of trying to support students who come into the class that maybe are caught off guard and are trying to grow as a learner and grow into the level of rigor that the course requires. I think allowing credit is a nod to that process.” He also believes there is merit in preparing for a high stakes exam.

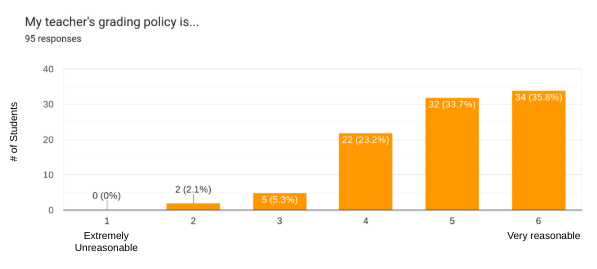

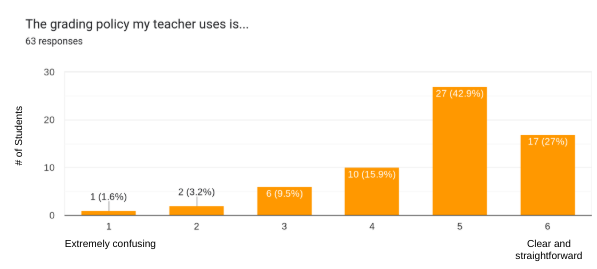

Student Feedback:

Teacher: Chris Lodore (they/them)

Classes taught: Physics

Years taught at Grant: 6

Grading policy and philosophy:

All summative assignments in Lodore’s class have a rubric attached and account for 70% of the grade. The other 30% of the final grade is based on formative assignments. The rubrics consist of a six-point scale ranging from highly proficient — six points, equal to 100% — to developing proficiency, which is three points and 50%. Lodore uses a six-point scale to ensure an easier transfer between proficiency and letter grades and because of the equitable benefits of proficiency.

Lodore weighs recent assignments more than past assignments. This policy ensures that students can focus on present work and move on from past mistakes. They also say that this policy keeps students from being able to “sit back and coast” in their class after they have built up a certain number of points from past assignments.

Lodore will round up to the nearest whole percentage.

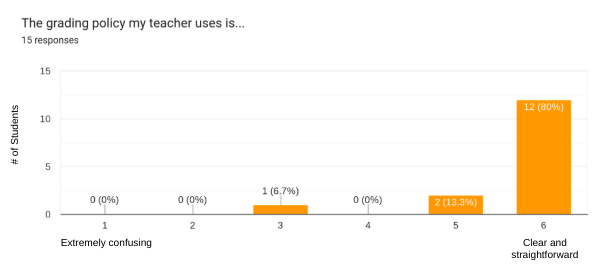

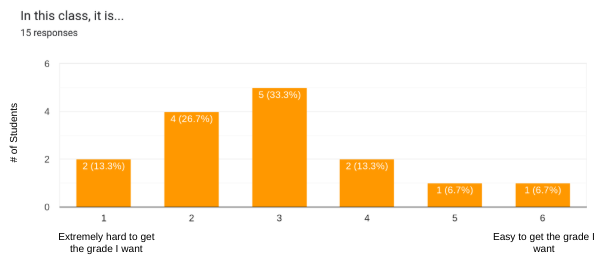

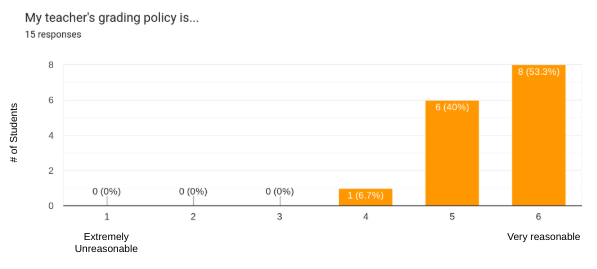

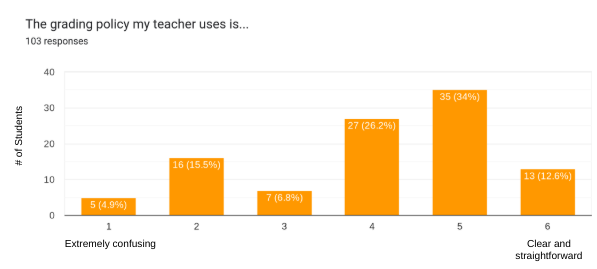

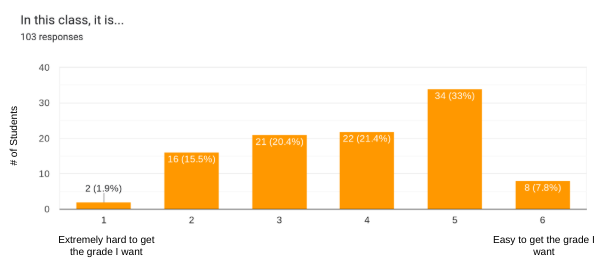

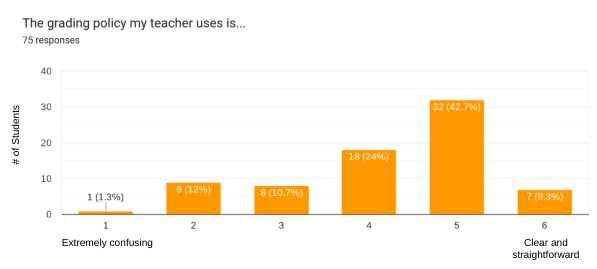

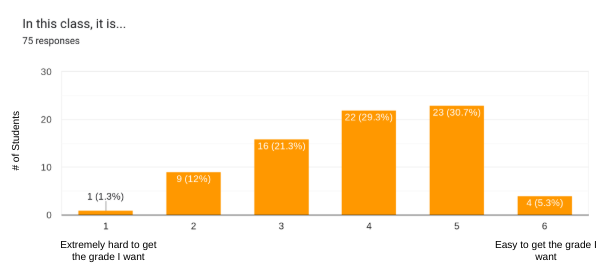

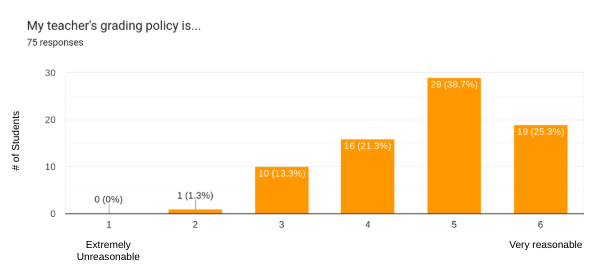

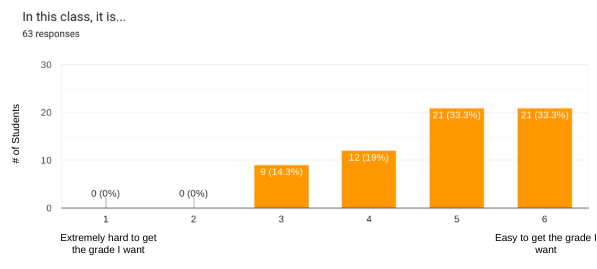

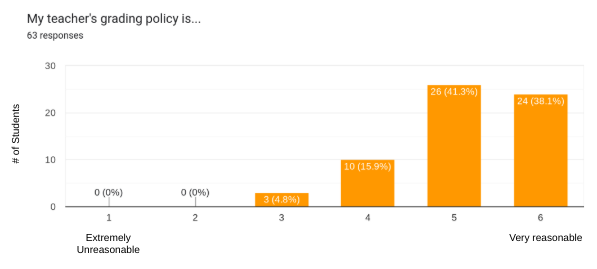

Student Feedback:

Teacher: Christina Aucutt (she/her)

Classes taught: Forensic Science & Biology

Years taught at Grant: 6

Grading policy and philosophy:

Christina Aucutt uses a four-point proficiency scale and states the standards and criteria for each proficiency score using rubrics. Summative work makes up 80% of the grade, while the other 20% is based on formative work. Aucutt uses synergy to transfer a student’s proficiency grade into a letter grade. She says this can be confusing, because a three out of four might look like it equates to a 75%, even though it actually equates to a B letter grade.

Aucutt likes the equitable and unbiased benefits that come with a proficiency grading system. “(The traditional point-based system) is focused on how many points you earn and not what you learn,” she says. “There’s more room for failure than there is for success, because a D is 60% … it’s a small margin, it’s like 20 points out of 100 can get you to a B or an A. And it just seems ridiculous that there’s all this other space.”

For missing assignments, Aucutt does not give students zeros, instead grading the assignment a 1 out of 4 for “Did Not Demonstrate.” She says she does this so that “If a student’s sick or they’re struggling or whatever it is, they don’t see zeros, because I feel like seeing a zero is defeating.”

Aucutt rounds up the final semester proficiency grades of all students in her classes to the nearest decimal place, because she believes that rounding will make up for any possible margins of error involved in the grading process.

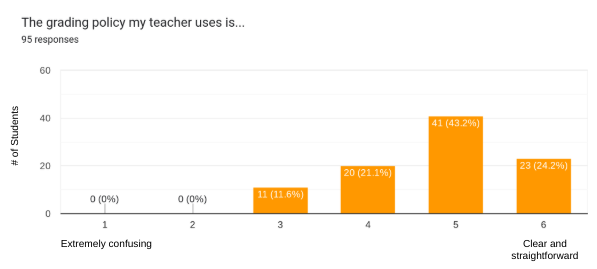

Student Feedback:

Teacher: Don Gavitte (he/him)

Classes taught: Government and Economy, PSU Global Cities and PSU World Civilizations

Years taught at Grant: 26

Grading policy and philosophy (Government and Economy Only):

Don Gavitte assigns a certain number of optional and required assignments each quarter which are each worth a different number of points. He requires students to fill out an individual plan, in which they write down the assignments they plan to complete to gain the required amount of points for their desired letter grade. In order to earn an A, students must earn a total of 90 points throughout the quarter and receive at least a 70% on the quarterly exams.

Gavitte says that he would not grade the way he does if it was not for the fact that many of his students have 504’s or other accommodations and one-third of Grant’s students are chronically absent from class. He says he would like to grade his Government & Economy classes “more like my PSU classes, because most of our students are going to college, and they should have grading systems that reflect college.”

Instead, Gavitte has built his system to better work with student accommodations and absences. “In the ‘gov and econ’ classes, there’s more choices, and assignments will reflect the skills (students) need to show for graduation, but they’re not as high stakes (as in my PSU classes),” he says.

Student Feedback:

Unavailable.

Teacher: Jackson Gilbert (he/him)

Classes Taught: Living In the U.S

Years taught at Grant: 2

Grading policy and philosophy:

Gilbert categorizes his Living in the U.S assignments into summative assessments, which are worth 70% of the total grade, and formative assessments, which make up the remaining 30%.

Gilbert believes weighing larger assignments heavily will prepare his students for life after high school. “In life, generally, the big stuff is worth more … and in school … What we need to teach young people to do … is that there are these big moments where you kind of have to get it right. You don’t get to try again often,” he says. Gilbert also grades formative work because, despite the fact that he does not believe grades should be the sole motivator behind student work, he would like to incentivise day-to-day activities.

In his class, summative assessments range from major essays to large-scale role playing simulations. For written assignments, Gilbert uses a rubric, grading a student’s ability to convey a topic to a particular audience. He says, “The way I think about my class is, I could either teach them history, or I could teach them how to be historians.”

Gilbert uses standards-based grading rubrics, which show whether or not a student is approaching, meeting or exceeding the expectation. This style of rubric helps explain students’ level of ability to apply different skills. The vocabulary also allows him to convey that “if you’re in ‘approaching the standard,’ you’re not failing. You’re not an awful person who’s not doing well in school … you’re working towards getting to where you should be, which is fine.”

Gilbert rounds grades at a 0.7% and above, but only if the student has a conversation with him and proves that they have earned the grade. He accepts late work up until the end of the following unit. All late work grades are capped at 90% because he believes that timeliness and organization is 10% of every assignment. As a freshman teacher, Gilbert wants to help his students build the skills they will need in high school.

Student Feedback:

Teacher: Keith Stoker (he/him)

Classes taught: Algebra 1-2 & Algebra 3-4

Years taught at Grant: 3

Grading policy and philosophy:

Stoker’s Algebra 1-2 students’ grades consist of 90% tests and 10% homework, while his Algebra 3-4 class’s grades are composed of 90% tests and 10% final exam grade. Stoker’s Algebra 3-4 class’s grades do not include a homework grade because the grade was thought to be inflating the grades of students who copied off the answer key, while deflating the grades of those who did well on the tests, but were unable to complete all of the homework. Stoker wants to grade learning and knowledge over compliance, and this approach has led him to not grade students based on attendance or, for some classes, homework.

Stoker’s tests are graded with a rubric set on a scale of four to seven to ensure an easy transfer from proficiency to percentage grading. This rubric ranges from highly proficient — seven points, equating to 100% — to developing, which is four points and equal to 57%. Each rubric has a list of standards that apply to different test questions, and a student will receive an overall score based on how well they fulfill the standards on each question. The goal of Stoker’s rubrics is to make it clear to students why they are receiving their grade and to encourage them to reflect on their learning.

Due to the fact that the policy assures the lowest score a student can receive on a test they complete is 57%, Stoker has raised the minimum grade required to pass the class from the traditional 60% to 65%. Stoker is more willing to round up lower grades than higher ones, although he says he is likely to round up an 89.9%. Stoker says he wants his students to feel as though they earned the grade that they received.

Student Feedback:

Teacher: Michael Williams (he/him)

Classes taught: Government & Economics and Psychology

Years taught at Grant: 17

Grading policy and philosophy:

In Williams’ classes, no assignments contribute to students’ final grade. Williams uses this policy because he believes the motivation to do the assignments should be born from the desire to build knowledge instead of earning points.

Williams used a proficiency model for about four years before switching to a percentage scale in order to fit the letter grade system used on college transcripts. Williams has adapted how he uses his 100% scale on all his tests to still hold the core values of proficiency grading. When Williams grades his tests, he raises the highest score out of his students to 100%. Each of his other students’ grades are raised depending on their relationship with the score of the highest graded student.

Williams is skeptical about rounding up grades because he believes the rounded number may become lower over time. Williams will, however, alter grades for certain situations, such as if a student has a single test score much lower than the rest.

Student Feedback:

Unavailable.

Teacher: Mikaila Donalson (she/her)

Classes taught: AP Human Geography

Year taught at Grant: 3

Grading Policy and philosophy:

Donaldson uses a four-point scale ranging from a 4 for advanced to a 0 for no data. All summative assignments use the same four-point scale.

Donaldson does not accept late work unless a student has a 504 plan or IEP, which are majorly accommodations for students with learning disabilities. She believes this policy prepares her students for the real-life workforce by teaching them the importance of timeliness. “I’ve really always had pretty strict policies when it comes to late work, just because I think (flexibility with late work) does set students up in this negative cycle where (they’re) constantly trying to catch up, and then it’s just a huge stress and huge overwhelming experience … wherever that grading would fall,” she says.

Donaldson recently changed her policy for her AP Human Geography summative country projects because of this philosophy. Instead of allowing students to turn in late projects without the ability to revise their work, she does not allow any late work or revision after submission, but conducts check-ins in the middle of each project. She also says that the change has been “helpful for me in managing my ability to provide really good feedback, because I don’t want to do okay feedback twice, I want to do good feedback once.”

Donaldson will round up grades up to the nearest whole percentage if a student shows consistent participation and growth in her class. Donaldson is more inclined to round up grades since all sophomores are required to take AP Human Geography.

Student Feedback:

Unavailable.

Teacher: Mykhiel Deych (they/them)

Classes taught: English 3-4 & Feminism and Gender Studies

Years taught at Grant: 11

Grading policy and philosophy:

Mykhiel Deych designs their grading policy so that formative assignments make up 25% of the grade, summative assignments make up 60% of the grade and responsible scholarship — the kind of community member a student is and their ability to submit work on time — makes up 15% of the grade. They say that they have changed their responsible scholarship to take up 15% of grades, rather than 10% , because they believe that A-students should have to maintain some degree of responsible scholarship.

Deych’s summative assignments are all graded on a point-based rubric, with the lowest possible score being a 50%. “The way that I think about (my rubrics) in my brain is a proficiency style approach … but I use points and not the four-point scale, because … we’re at the end of a system that doesn’t use proficiency scale with (fidelity),” they say.

Deych does not give feedback on work that is turned in late, although they say they will give feedback no matter what if a student comes to their class during flex. They have a two-week late work extension, but will take late summative work if a student has an F or a D in their class. Deych is motivated to create a system that is equitable, while also holding students accountable and ensuring that they are not grading a large amount of work at one time.

This year, Deych is not rounding up grades because they believe they have already provided students with ample chances to boost their grades.

Student Feedback:

Unavailable.

Teacher: Ramey Adams (she/her)

Classes taught: Chemistry

Years taught at Grant: 4

Grading policy and philosophy:

Adams splits assignments into two categories: summative and formative. Summative assignments take up 70% of the grade and include unit tests. Formative assignments make up the other 30% and include classwork and quizzes. She allows retakes on tests, as well as test corrections, in which students can receive up to an 85%.

Adams grades tests using points, not a proficiency scale. “I think we just don’t have enough understanding of how proficiency grading works,” she says. She adds that teachers have too many students and not enough time to create a large number of proficiency-based assignments while simultaneously communicating with parents on how proficiency works.

For some classwork, however, Adams does use a proficiency scale and a rubric. She tries to reinforce the importance of a student’s ability to communicate their understanding of the content.

This year, Adams has added a policy in which she will only round up a student’s grade if they have no missing assignments. Adams tells her students that it is a good idea to turn in and revise assignments, even if just to one point, because that revision could make a difference in their final grade.

Adams believes it is important for students to take responsibility for their own grades, but also know the grades they get are not the only measure of their success.

Student Feedback:

Teacher: Randy Heath (he/him)

Classes taught: Health 1-2

Years taught at Grant: 11

Grading Policy and Philosophy:

Randy Heath uses a point-based system and does not divide the points into formative and summative assignments: All tests and assignments are weighted only on point value throughout the semester. He believes every student has the ability and opportunity to obtain an A in his class. “My focus is probably not as much on the grade as it is (on) how to put what we cover in a health class to practical use,” he says. His philosophy leads him to work with his students in whatever ways he can, coming up with alternative methods to make up missing work.

Heath rounds up grades relatively subjectively, depending on observed student engagement, although most often he will round up to the nearest whole percentage. Once a quarter ends, students are not allowed to go back and revise or make up any assignments. Heath encourages students to stay on top of their work and come to him if they have any questions or missing assignments.

Heath values students being present and engaged, and attendance can affect a student’s grade in his class. If a student is engaged and an active participant in class but their grades on assignments are low, Heath is willing to make adjustments if he sees that the student understands the content. He strives to create a classroom environment where students are confident and comfortable engaging.

Student Feedback:

Unavailable.

Teacher: Sunshine McFaul (she/her)

Classes taught: AP Language and Composition & English 5-6

Years taught at Grant: 10

Grading policy and philosophy (AP Language Only):

McFaul uses a contract-based grading system, which sets expectations for students and promises a certain grade if they complete the required tasks on time. “If I’m assigning something, it’s because it’s … really important practice, it’s looking at a specific skill. It’s not meant to be busy work,” she says. “So that’s why, with contract-based grading, if you’re doing what I’m asking you to do, you’re getting what I need you to get. So I’m not going to have your grade be impacted.”

McFaul chose to use contract-based grading because she wanted to find a system that compromised between having a large focus on grades and not having any at all. She believes her system puts a greater emphasis on learning than it does a grade.

Mcfaul says it is difficult to communicate her policy because the tools teachers use, such as Synergy and Canvas, do not align with her philosophy. The fact that students have grown up very focused around the number grades and a point system is an additional barrier to explaining her policy.

Student Feedback:

Unavailable.