Content warning: This story includes details about panic attacks and suicide.

It’s a recent school day, and sophomore Nina Conable’s vision blurs. She feels nauseous and her heart rate begins to speed up. For her, these are warning signs of a panic attack.

Conable grabs a blue slip of paper from her backpack — a pass that allows her to leave the classroom when on the verge of an attack — and heads toward the classroom door, holding it up for her teacher to see.

The pass is supposed to grant Conable an easy exit out. But her teacher stops her, telling her that he doesn’t know what the pass is and asking her why she’s always leaving class. Conable makes up an excuse about needing to see her counselor and rushes out the door, heading toward the nearest single-stall bathroom and locking herself inside.

She takes deep breaths in an attempt to center herself. Running her hands along the walls, her fingertips find the different textures of the ceramic tiles and the coarse sealing. Out loud, she describes her surroundings, vocalizing every detail she notices about the beige bathroom stalls and the cool temperature of the room, bringing her mind from a state of panic back to reality.

When Conable’s panic attack ends and she finishes her 15-minute walk around the hallways, she returns to class. Her teacher immediately bombards her with questions, asking her where she was and if she skips her other classes as well. Conable dismisses the teacher’s questions, instead saying that she just needed to take a walk, and goes back to her seat.

“Some of (my teachers) are kind of accusing about (my leaving class),’” says Conable. “Like I was doing something wrong.”

For kids struggling with mental illnesses at school, this is often their reality.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, a mental illness is “a condition that affects a person’s thinking, feeling or mood.”

Conable has depression and anxiety and shows many symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). To ensure Conable would receive help for her anxiety and ADHD symptoms in the classroom, Conable and her parents worked with her counselor and Grant’s school psychologist to put a 504 plan in place during her freshman year — a plan recognized by the state of Oregon assuring that those who have disabilities receive the specific accommodations they need in order to be successful in an academic setting.

However, Conable feels that her teachers don’t often uphold the responsibilities that are stated within her 504 plan. “I’m asking for help, which a lot of kids are free to do, and even with me going out of my way to talk to my counselor and do all these things, I still don’t feel like I’m succeeding in the environment,” she says. “Even though I’m trying my best.”

Most Grant students are required to spend seven hours a day, five days a week, for about 36 weeks a year in school. But in a school whose mission is, “Every student matters, every students succeeds,” too many students struggling with mental illness feel as if they are not receiving the support necessary in order for them to be successful.

This isn’t just a problem at Grant. According to a 2016 article by National Public Radio, in a class of 25 students, five may struggle with mental illness. Yet 80 percent of those kids are not provided with mental health services, in or out of school.

When students don’t get resources, there can be drastic consequences. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for adolescents ages 10 to 24 years old in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ninety percent of individuals who die by suicide experience mental illness, and yet the stigma around mental illness has often made resources inaccessible.

Historically, those struggling with mental illnesses have been shunned from society and placed in mental institutions or jail rather than given resources and support. Brenda Martinek, the director of Student Support Health and Wellness for Portland Public Schools (PPS), remembers mental illness being a taboo topic when she was growing up. “If you had somebody with mental health issues, a lot of them would be called ‘crazy,’” she says. “And that’s such a negative connotation to the struggles and the real issues that people with mental health issues have.”

The stigma can be severely harmful to students who struggle with mental illnesses. Grant junior Ashton Allen struggles with depression. When describing his mental illness, Allen says, “You can never catch a break, you’re always exhausted. It’s just a constant gray cloud you have to force yourself to walk through just to get through life.”

Allen believes that because of the stigma around mental health, those who experience mental illnesses often downplay their symptoms to avoid making others uncomfortable.

“(The stigma) is very internalized,” says Allen. “People (with mental illnesses) are just afraid of talking about it because they don’t want to burden someone else with their problems.”

That fear leads to limited education around mental illness and in turn the limited education results in increased stigma, creating a perpetual cycle. The training that teachers do receive surrounding mental illness is focused on mandatory reporting and referrals to counselors instead of education about mental health.

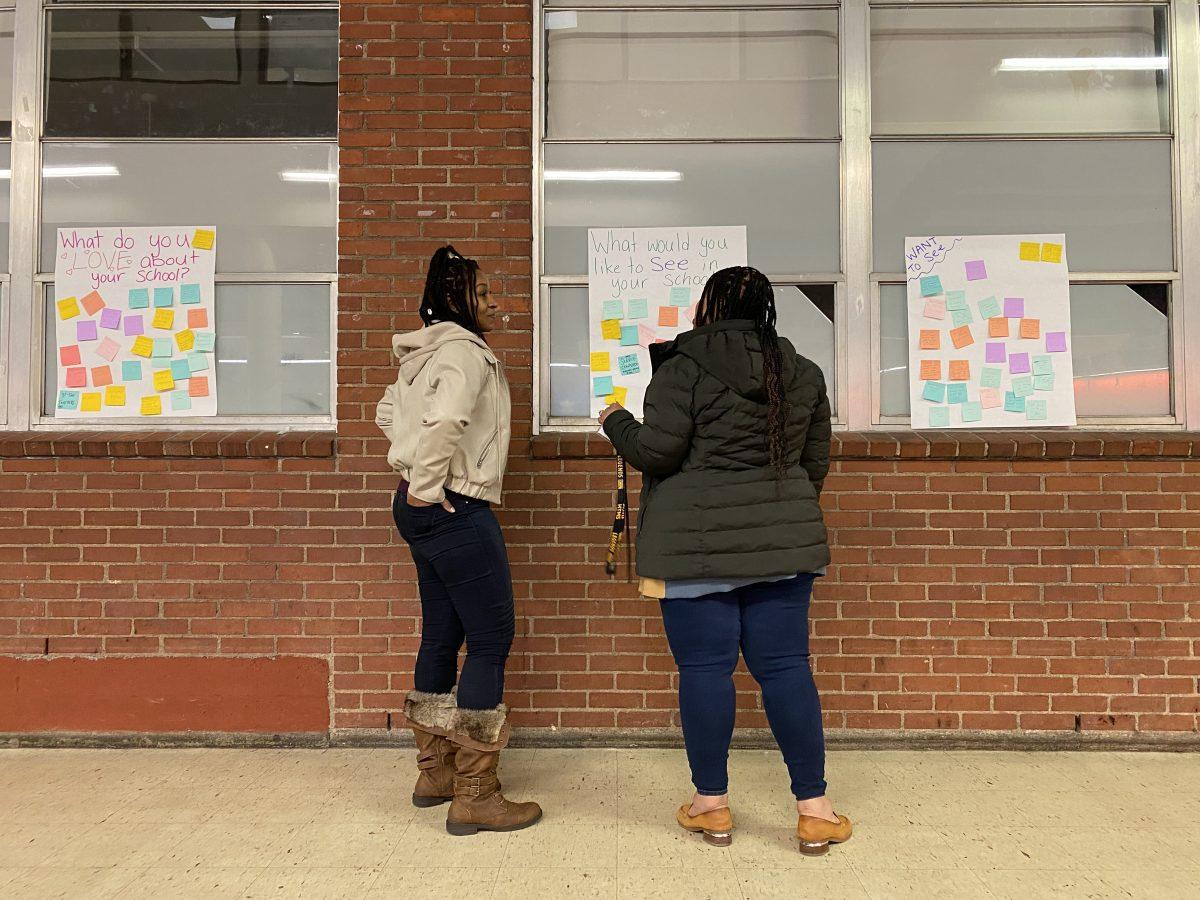

“I don’t think we have enough (resources),” says Grant principal Carol Campbell. “I think that we’re becoming more and more aware of the struggles that teenagers have around mental health or can have … We all just could have a deeper understanding of how we could be as supportive as possible for a student who’s struggling.”

Like many kids, Conable’s experience with mental illness started early. Throughout elementary and middle school, she struggled with speaking in front of her classmates and had trouble focusing in her classes.

After experiencing frequent panic attacks in middle school, she began getting treatment for anxiety and depression, though receiving the diagnosis was a long process.

“It was hard for me to talk to people … because I would talk to one doctor, who would send me to another doctor and so on,” says Conable. “I ended up talking to a few people, and it was stressful for me to have to talk to these strangers about this sort of personal aspect of my life.”

During her freshman year at Grant, her difficulties with focusing intensified. She would sometimes miss big parts of lectures or read with little comprehension. At first, she attributed her inability to focus in school to her anxiety — but when therapy didn’t change anything, she realized there might be something else going on.

Conable’s struggles were heightened because she wasn’t receiving any education about mental illness. On top of that, none of her friends could relate to what she was going through. “I felt isolated,” says Conable. “Not really having anyone to talk to about it who understood and could be empathetic about it … made it feel like I was going through it alone.”

The lack of education surrounding mental illness leads some kids at Grant, Conable included, to educate themselves about what they are going through.

So, when focusing grew steadily more difficult, Conable turned to the internet.

After delving into online clinics and resource pages, Conable found that all of her symptoms pointed to ADHD. She felt instant relief. “I was like, ‘Oh maybe I’m not just dumb, maybe there’s something actually going on with me,’” she says.

Conable went to her parents, explaining everything she had experienced in school and what she had found through her research. At first, Conable sensed a “get over it” mentality in her parents’ reactions, an attitude that is prevalent among many adults today.

“When Nina first talked to us about being depressed, I would say that I started approaching it the same way I was brought up, like ‘Oh, you’ll get through this. This is a hard time. It’s hard for everybody,’” says Conable’s mother, Vicki Conable. “But you know, the anxiety was real, and the depression was real, and by the time she was 15, it was like, okay is there something else leading to the anxiety and depression?”

Because the parents of many students now were taught to suppress mental illness during their formative years, they often don’t talk to their children about mental health at home.

When Allen was in eighth grade, he began to notice how he was struggling to stay alert and concentrate on work more than he used to. But, like Conable, when communicating these feelings to his peers, he found that they didn’t understand.

After doing some online research on his own, Allen opened up to his mom about his symptoms; he believed he had depression.

Allen’s mother, Vickie Vaughn-Allen — who has experienced depression since she was a child — was unsure of how to support him, as she hadn’t received support from her parents for her own mental illness.

“A lot of things, we kicked under the carpet instead of facing head-on. So it was more, if you were dealing with something, you dealt with it yourself, and you kept quiet about it,” remembers Vaughn-Allen. “I definitely understand what he’s going through, but even though I understand, my parents weren’t there for me, and they weren’t an outlet for me, so I didn’t know myself how to be an outlet and how to be there for him myself.”

Allen and his mother began to do research together. Allen came upon the official website of Mayo Clinic, a non-profit medical research group, which became his primary source of information.

“If I didn’t educate myself about mental illness, who else was going to?” says Allen.

After researching his symptoms, Allen eventually worked up the courage to speak with his mom about going to see a professional therapist to receive an official diagnosis. “Someone on the outside looking at that conversation would see it as a very easy conversation, but it was very hard talking about it because I was very uncomfortable with opening up about something that personal,” he says now.

Allen received a diagnosis for depression from his therapist. But his self-education stuck with him.

Emma Burris, a sophomore at Grant with anxiety, remembers receiving limited education on mental illness as well. It was discussed once in her sixth grade health class, but Burris says it wasn’t enough. “Nothing was really covered; it was just like, ‘Talk to a teacher if you’re sad,’” she says. “No real like description or … what felt like genuine support.”

For Burris, the limited education made her feel alone. “Looking back and talking to people that went to my middle school, lots of people were dealing with (mental illness),” Burris says now. “No one was talking about it. There was no person to go to, no one really knew what was going on with them.”

The lack of education continues in high school. Depending on the required health class a student at Grant takes — whether it is through the Fit 2 Live and Learn program or through a stand-alone class — Grant students get some education surrounding mental health. But for many, those classes are the first form of education they get, and some Grant students don’t take a health class until their senior year.

“I think education should start way sooner than when you feel like you might have a mental illness and you need to Google it on your own,” says Burris. “I feel like there’s not really any conversation at all unless there’s a specific teacher that realizes that needs to happen. And even if it happens in one classroom, that’s not enough. It should be happening in every classroom.”

But when teachers themselves don’t receive education surrounding mental illness, educating students becomes substantially more difficult.

PPS teachers receive little information on mental health district trainings. Although they are required to take about five hours of online health and safety training courses that consist of slideshows, only one touches on mental health.

The slideshow focuses on mandatory reporting and signs of suicidal tendencies. But when education focuses on suicide, the years of mental illness that often come before are neglected. Burris has had multiple experiences with suicidal ideation. The therapy she attends helps prevent more suicidal thoughts, but her experiences made her realize she had been invalidating her own struggles. “I was just thinking, ‘I can’t be depressed because I’m alive, and I haven’t killed myself, and so I don’t need help, I don’t deserve to have help because I’m not at that point,’” she says. “When I was having suicide ideation, that was kind of a wake-up call for me, and I think it’s kind of sad that it had to get to that point for me to realize that I actually do need to get actual help.”

Burris says she rarely feels comfortable talking to teachers about her experiences with suicidal ideation. She feels that most of her teachers don’t incorporate mental health into their curricula. Scott Blevins, Burris’ freshman English teacher, is one of the only teachers she feels comfortable with, and she often goes to his classroom when she feels too anxious to function in her own classes.

Blevins — who tries to be open about his experiences — has had depression since his early childhood. He feels that teachers have a responsibility to their students in terms of their mental health. “I remember when I was in high school, I felt really isolated, and there weren’t very many adults who I felt I could connect with,” says Blevins. “But the few that were there were really awesome and kind of changed my life.”

But in order to help students effectively, Blevins says teachers need more training than the hour-long slideshow about mandatory reporting. “There are all of these expectations put on teachers to be protectors and caregivers and psychologists and social workers and educators,” he says. “But then there really isn’t always a lot of time and energy given to teachers understanding the myriad world of mental health and what that looks like in your classroom and what that looks like in kids.”

Instead, teachers are trained to hand students off to counselors or the school psychologist if they have concerns, rather than approaching the student themselves. “If somebody … looks like they might be hurting themselves or looks like they might be depressed or suicidal, any of that, (teachers are) mandatory reporters,” says English teacher Richard Meadows. “I usually check in with school psychs and stuff. Because it’s really out of my domain (to approach students).”

For students, asking for help from family members can also be difficult.

Though Conable describes her relationship with her parents as close, coming to them about her research was a big step. “At first it was kind of frustrating because they didn’t really believe me,” she says. “I had never really talked about it before, and I was having this trouble, and I didn’t know what was going on with me … I needed this help, and I was asking for it finally.”

As Conable spoke more about her research, her parents began to understand what she was going through. Though at first they were hesitant, they agreed to test her for ADHD.

“I felt kind of like a test subject cause it’s not like a thing like when you break a leg (and) you can go and get it X-rayed, and it’s very medical and they know immediately,” says Conable. “(Instead) you have to take all these funky tests.”

During the testing, it was confirmed that Conable has a processing deficiency. But she qualified as “above average” in the spatial awareness symptom, which meant the results of the ADHD testing came up inconclusive.

When Conable’s doctor suggested she look into getting a 504 plan, her initial reaction was hesitant. “I felt really afraid to talk to my teachers about it,” says Conable. “I was … ashamed that I needed more help than (my peers) did because it made me feel dumb.”

With the help of her parents, Conable was able to obtain the plan easily after meeting with her counselor and the school psychologist. The plan they put together provided Conable with extended time on writing assignments and tests, a heads-up on reading assignments and the blue pass that allows her to leave class when necessary, among other things.

But putting the plan to use was a different matter entirely. Many of Conable’s teachers have frequently forgotten about certain accommodations she needs.

“I ask (my teachers) for help with stuff that’s in my 504 plan, and they don’t know what’s going on, they’re not in the loop at all,” says Conable. “I feel like they say they’ll help me, but when I actually need their help they’re not there for me.”

This year, the structure of one of Conable’s classes — focused on reading and comprehension rather than hands-on activities — causes her severe anxiety, to the point where she often can’t walk through the door without having a panic attack. “Public schooling is very focused on one way of learning,” says Conable. “It’s this system of just getting people through and not really worrying about the people that you leave behind.”

When Conable approached her counselor about the issue, she was presented with two options: meet with the teacher of the class to discuss possible changes, or drop out of the class and attend summer or night school. The possibility of switching classes was unlikely, as the other class was full and would only become an option after speaking with the teacher.

“Talking to the teacher, that’s not an option for me because just like thinking about it freaks me out,” says Conable.

Conable felt like she had no way to fix the problem. “I feel like they gave me an option that wasn’t good, and it was either that or figure it out myself,” says Conable. “I ended up just staying in the class, and it’s not a good situation, and I don’t feel comfortable with it, but my other options aren’t any better.”

Now, Conable attends therapy once every other week and is taking medication for her anxiety and depression. “In a lot of ways they’re connected,” says Conable about her ADHD symptoms and her anxiety. “I can’t feel good with anxiety unless I’m being successful in school, but I can’t feel successful in school unless I’m doing good with my anxiety.”

Despite the already limited resources at Grant, just last year another one was taken away. Until this year, Grant held one of eight school-based health centers in PPS. The health centers, provided by Multnomah County, allow students to receive medical services free of any cost to students without insurance.

Through the health center, students had access to a host of health services, including receiving antibiotics or vaccinations, physical exams, and information regarding outside resources. Students could also book appointments with an in-school therapist.

However, the clinic was lost in the transition to Marshall. “The county has pulled out because the socio-economic status of students that are going to Grant doesn’t meet … the criteria for a school-based health center going into a community, because they need people who are eligible under the Oregon health plan,” says Martinek.

She explains that the loss of the Health Center is due to a combination of under-utilization, and because, on average, the majority of families at Grant are likely able to pay for healthcare outside of school support.

The health center was not relocated to another PPS school, and although a new in-school therapist was placed in the school, they are only in school one and a half days a week. For Grant students, the removal limited the already scarce resources.

“(The health center) gave me a place where I could just talk about my problems free of judgement,” says Allen. “It makes me kind of angry because people should have access to that, no matter where they are.”

Though Allen, like Conable, regularly attends therapy for his depression, he stills feels uncomfortable in many of his classes at Grant. “The fear of messing up, saying something stupid or doing something stupid causes me to avoid tasks or problems that would involve me talking to others,” he says. “I try to keep to myself more … I always have this irrational fear, like, oh my gosh, what if I hold back the group? Or what if I say something that’s misleading? Or if I get off task and then I’m completely lost in the subject and I don’t know what’s going on?”

The judgement Allen receives, like many other students struggling with mental illnesses, can show up in casual conversation.

Jokes about mental illness and suicide can be heard in the hallways and classrooms of Grant. Teachers and students alike often make heavily-loaded statements about different mental illnesses, such as depression, ADHD and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). To some, the negative impacts attached to these jokes go unnoticed. However, these comments promote the idea that mental illnesses aren’t something to be taken seriously.

“Lots of people make jokes just going around that they’re going to kill themselves,” says Burris. “People don’t realize that saying stuff like that can be really triggering and … impactful to the people around them. It’s easy when you’re not that attached to something … to just kind of throw it around if it makes you uncomfortable. And maybe if you make it a joke then it’s not so scary.”

Students and faculty both agree that better education around mental illness would not only lessen the stigma around the topic but also make it easier for students to get support and resources.

“People get scared of the unknown,” says Martinek. “And I think that when they do that … they often view it in a negative way. We have to understand (mental illness), we have to understand the causes and then understand that it’s an illness, and it’s treatable.”

Martinek believes that changes are slowly coming about, but there is still a lot that needs to be done.

“We, as a county and a system, are just now starting to understand the impact that mental health has on education and the social (and) emotional health of students,” says Martinek. “It’s more in our face now, and I think it’s forcing people to look, to understand it, and to hopefully start to help people.”