It’s not easy for Officer De Shawn Williams to explain to his young sons that in the future they will be targeted by the police. “I know. I know. I am the police too,” he tells them, but he knows it doesn’t matter. They’ll understand soon enough.

Williams, who represents the Portland Police Bureau as Grant High School’s Student Resource Officer, is an African-American father of three. He knows the skin color of his children may leave them susceptible to the same unwarranted police screenings, confrontations and violence he has experienced.

The recent shooting of Michael Brown, the unarmed young black man who was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Mo., has pushed the issue of racial profiling front and center. For many, the Ferguson situation may feel safely distant. But for a number of African Americans in the Grant community, Ferguson is a stark reminder of the impact that race has on their lives.

“Racial profiling is very real,” says Grant counselor and head football coach Diallo Lewis. “I have so many experiences that they all seem to run together.”

Lewis concedes the frequency of his encounters with police have dwindled with age. He says his real concern is with young black men, who are stopped by the police at alarmingly high rates.

“People say, ‘Oh that’s Ferguson. That’s in Missouri. That doesn’t happen here,’” Lewis says of the recent shooting. “It does happen here.”

Lewis is right. In 2010 alone, two young black men, Keaton Otis and Aaron Campbell, were shot by police in Northeast Portland.

African-American students at Grant speak of being confronted by police on a regular basis, not for criminal activity, but because of their race. The situation leaves them and their parents distraught.

“If you’re young and black in this town, you’re going to attract more police attention because of the color of your skin. That’s so incredibly horrifying to me.” – Jeremy Reinholt

Grant senior Duarte Papa-Vicente says he’s faced a lot of unwarranted police attention since moving to Portland from Angola three years ago. Papa-Vicente, 18, is a dedicated student athlete who plays on Grant’s varsity basketball team. But his six-foot, four-inch height and dark complexion, he feels, can sometimes draw a lot of attention.

“I’ve gotten stopped so many times I can’t even count,” he admits, estimating that each month he is approached and questioned by police around three or four times.

On a fall day last year, Papa-Vicente was on his way home from football practice and was crossing a street near the Moda Center. As he was heading to the bus stop, three police cars pulled up and stopped abruptly at his side. The surrounding traffic was forced to a halt, Papa-Vicente recalls, and all eyes were on him.

The officers leapt from their cars and began questioning him. One officer had his hand ready on his firearm, Papa-Vicente recalls. “I thought he was going to shoot me,” he says now.

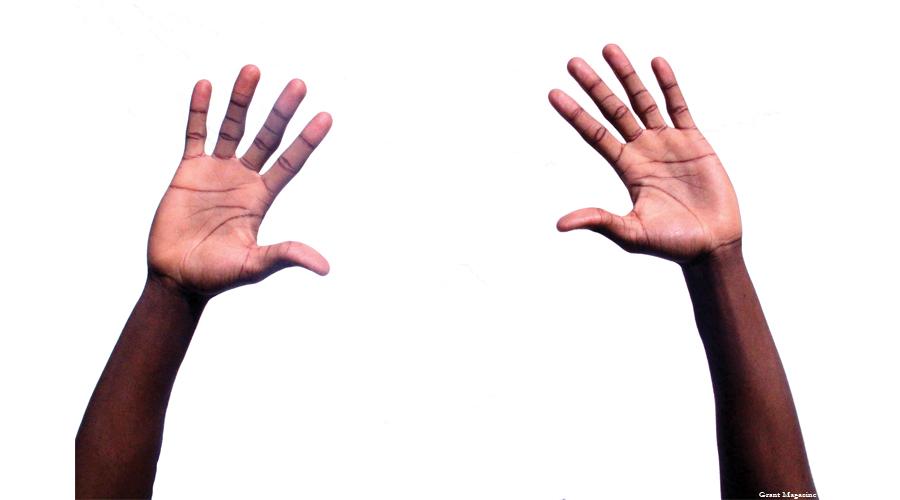

The cops were looking for a suspect and Papa-Vicente did what his mother always tells him to do when he encounters the police: remain calm with his hands free and in the air. Once the cops were able to determine through questioning that Papa-Vicente was innocent, they pulled away.

In Portland, statistics show that young black males run a much higher risk of being stopped by the police. Numbers from Portland Copwatch, a longtime citizen-run community group, show that African Americans are 2.4 times more likely to be pulled over while driving than whites in Portland.

About 19.5 percent of pedestrians who are stopped and questioned by Portland police are African-American. Many are vexed by this, given that blacks make up only 6.3 percent of Portland’s overall population. Accordingly, 2010 data by Copwatch shows African Americans who were stopped were more two times more likely than whites to be searched.

For Marty Williams, who is African American and serves as one of Grant’s resource staff members, it’s clear what’s happening in the city where he grew up: “I feel like young black men are targets,” he says.

Jeremy Reinholt, a history teacher at Grant who is white, says he’s disturbed by stories like Papa-Vicente’s.

“If you’re young and black in this town, you’re going to attract more police attention because of the color of your skin,” Reinholt says. “That’s so incredibly horrifying to me.”

Reinholt acknowledges the problem is glaring. But he sees some hope for the future. “Racism goes so far back and we just haven’t escaped it yet,” he says. “Every generation makes it a little better. Every generation is progressively dragging us out of this barbarism.”

Officer Williams says he will soon have to have “the talk” with his sons concerning their potential future interactions with the police. They are still young, but he wants to make sure they understand early on what’s at stake.

“Officers are supposed to profile based on behavior, not by race,” says Williams, adding that while many of Portland’s officers are respectful of this policy, plenty are not. “Racism exists here in the Portland Police Bureau,” he says flatly.

Williams knows from experience. He remembers walking down a Portland street one time when an officer told him he fit a description.

“Do I still fit the description?” he laughed, after establishing that he was a cop, as well. He carried on his way, but the memory lingers for Williams, who was born in Cleveland.

Williams and his family moved around a lot during his childhood. They spent a handful of years around the San Francisco Bay area and in Louisiana before settling down in Union City, Calif., where Williams attended James Logan High School.

He recalls having both positive and negative experiences with police. He was raised by parents who often fought and he remembers cops coming into his home to quell the chaos.

“I had to call the police to get my dad off of my mom,” Williams remembers. The officers were supportive of him in this situation. However, the police weren’t always on his side.

Williams was 17 when a police officer pulled a gun on him. Early one evening, Williams was driving in his hometown when he was pulled over for what he believes was a case of “DWB,” or driving while black, a phrase coined by members of the African-American community. It refers to the experience many blacks say they have of getting pulled over for a traffic violation because of what they believe is their race.

A regular day of minding his own business quickly shifted gears, leaving Williams in fear for his life. After a few moments of being on the side of the road, Williams was told to get out of his vehicle. Next thing he knew, the officer’s firearm was drawn.

“I still get nervous around cops and I am a cop,” Williams says.

During his high school years, Williams says he was a class clown. Still, he played football and graduated in 1994 with an athletic scholarship to Oregon State University.

“Without football, I wouldn’t be here,” Williams says, acknowledging that the sport he loved kept him away from things that could have gotten him into trouble. “I made the right decisions.”

As a powerful running back, his future looked bright. But Williams’ dreams of playing professional football were crushed by an injury that came during his first year as a starter in 1997.

For Williams, his injury was a wakeup call. If he had never before realized how unlikely ending up on a professional roster was, now he had. He began investing more energy into earning his diploma and graduated in 1998 with a history major.

In the years that followed, Williams took odd jobs and worked as a coach for track, football and wrestling. He was on his way to becoming a teacher in 2006 when he decided to come to Portland and join the police bureau.

Today as a student resource officer, Williams oversees nearly 10 schools in the Grant area. In addition to his regular duties as an officer, Williams is involved in community outreach and teaching youth about how to properly interact with the police.

Aside from being compliant and respectful, he wants students to know that “there is a time and place to argue.” But that time, he says, isn’t on the road after dark if you’ve been pulled over.

The list of incidents involving young black men having run-ins with law enforcement shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone in the United States. In Missouri this past August, a white police officer in a squad car approached the 18-year-old Brown and his friend, asking them to move out of the middle of the street and get on the sidewalk. A struggle ensued and Brown was shot.

After the first shot, Brown and his friend separated and fled on foot. The cop got out of the car with his weapon drawn and followed Brown, shooting him four times in the right arm, once in the eye at a downward trajectory, and once in the top of the head. Witness reports say Brown had stopped and had his hands in the air.

Protests, riots and calls for civil disobedience in Ferguson followed. The police are under scrutiny by the federal government and an investigation into the shooting continues.

At Grant, the Ferguson shooting resonates with some students. “It could have been me,” says Caleb Weekly, a senior who is African American.

At 17, Weekly says he is routinely stopped by the police. Interactions range from distrustful questions such as “What are you up to right now?” as he makes his way home from school to being pulled off the bus or MAX light rail for interrogation.

One time, police officers pulled him off MAX because they didn’t believe he looked young enough to be in high school. After over 30 minutes of questioning, they released him.

Racial profiling isn’t just something that happens with police, Weekly says. He often sees people pulling their children close or women gripping their purse tighter when he walks by. He recalls a time when his phone wasn’t working and he needed to call his mother.

He asked a white woman nearby if he could borrow her phone to make a call. She “vigorously shook her head no.”

“It scares me because where do I go for help?” Weekly asks. “Where do I go for help if I need it? We are looked upon like we’re the bad guys of society, like we are up to no good all the time. We just have to make sure we carry ourselves the right way.”

His mother, Chanice Weekly, is saddened and frustrated that her son is regularly stereotyped by law enforcement. She knows that on countless occasions her son and his friends walk together to the bus stop from school and are confronted by police officers.

In an ideal world, she believes authorities would judge people based on individual circumstances, rather than through stereotypical lenses. However, she knows that’s not always the case, and she teaches her children to be respectful in public and to authorities. “Don’t give them what they’re looking for,” she says to her children. “You stand out and you be a leader.”

As a history teacher, Reinholt sees the inherent conflict that’s at play when something happens like the Ferguson shooting. America was founded on the ideal of equal opportunity, he says. Yet he believes the country has a long way to go.

“If there are entire groups of people who are living in daily fear for their lives because they happen to have been born with a darker skin tone, what’s the point?” Reinholt wonders. “America is a lie if people have to walk around afraid for their lives every single day.”

Is Portland a safe place for young black men? Reinholt wonders. He knows the answer is complex, but believes it should be. He looks back to the 2010 police shooting of Otis in Northeast Portland. The 25 year old was shot at 32 times during a random police stop in traffic. Twenty-three of the bullets struck their intended target.

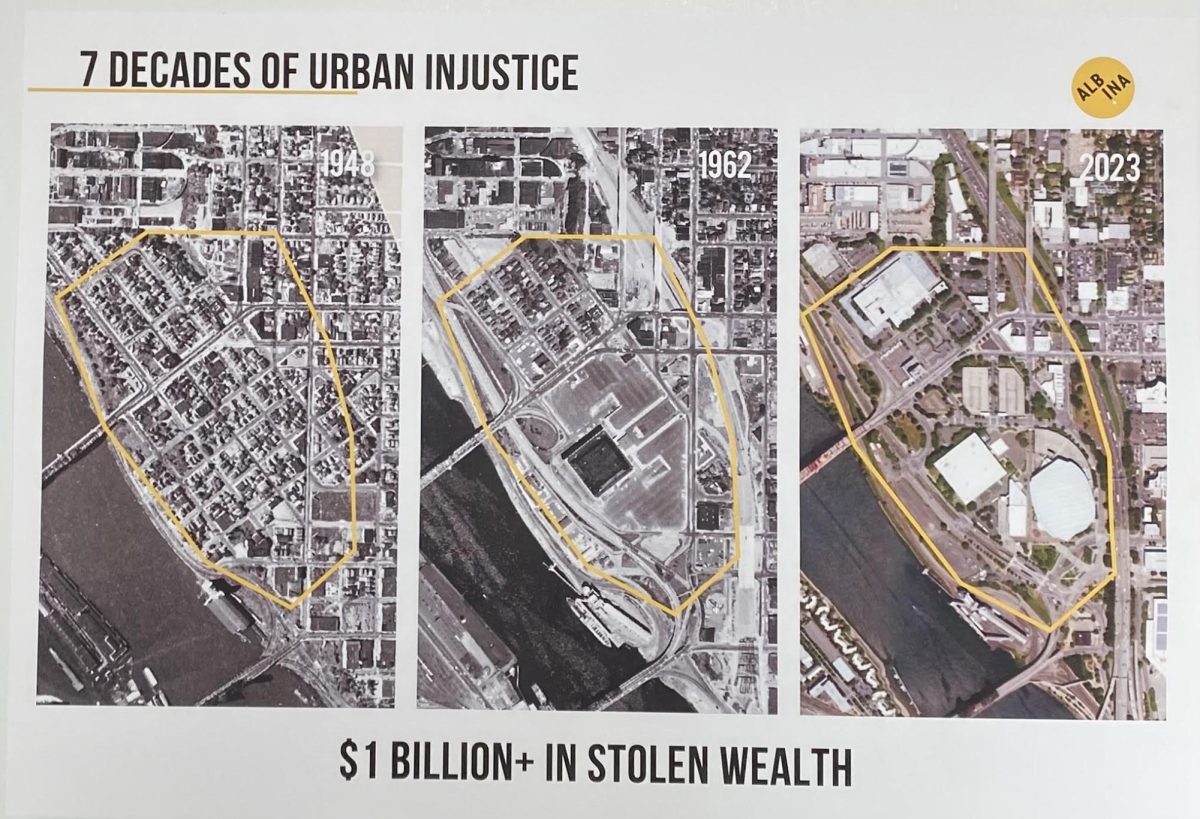

Reinholt also recalls the 2008 mock lynching of a cardboard cutout Barack Obama at George Fox University near Portland. He remembers Oregon’s long history of anti-African American legislation and Portland’s redlining policies. He looks back to the major historical prevalence of the Ku Klux Klan in Oregon and wonders more.

The history runs deep. Grant counselor Tearale Triplett grew up in Northeast Portland at a time when gangs were taking hold in the city. Triplett was never involved but was aware of the dangers.

“I was a school-first type of guy,” Triplett says. “I took school as seriously as possible. I looked at school as a ticket to a better life.”

Still, as an African American male, that wasn’t enough to stop him from getting profiled, whether he was walking, driving or going shopping.

Triplett recalls a summer night when he came to Portland on a break from his studies at the University of Oregon. He was with a group of friends who were African American and they were driving a few blocks from Triplett’s house when they were pulled over by a police officer.

He remembers one of his friends being somewhat indignant toward the officer, frustrated because they had not been doing anything wrong. Nobody in the car was armed and they made sure their hands were visible. Still, the officer drew his weapon.

“I knew then that there was a different set of rules for me as far as society was concerned,” Triplett says of being stopped by the police. “It’s embarrassing; it’s frightening.”

Officer William says state law allows cops more leeway to profile by race. He mentions laws such as the one that requires drivers to engage their signal 100 feet before the curb, explaining how it’s not hard to find an excuse to stop someone.

“There are a lot of ways to stop people” if you’re a cop, Williams says. He believes these laws contribute to the “driving while black” phenomenon.

For Marty Williams, it stings.

“I have a family. I go to work everyday,” he says. “I’m out here trying to be a positive figure in the community. But when I go to the store, I’m looked at as somebody of suspicion. It doesn’t feel good.”

Darryl Kelly Jr., an educational adviser who works with students at Grant, acknowledges that some African Americans play a role in perpetuating negative stereotypes that might influence police actions. Still, he believes racial profiling is wrong and he sees a solution.

“I think people in any professional field should have to take classes in cultural competence,” Kelly says. “They think we’re criminals just because of our skin tone. If they were culturally competent they would know that every culture has its bad apple.”

With a primarily white faculty and mostly white student body, Principal Carol Campbell sees great importance in cultural awareness, and she wants all members of the Grant community be aware of inequities. She says matter-of-factly: “Someone else’s life experience might be completely different based on that color of their skin.”

After the shooting in Ferguson, Campbell showed Grant’s faculty a YouTube video by The Oregonian titled, “The Black Boy Speech in America.” The two-minute video shows mothers of African-American children expressing their concerns.

In the video, the women tell the camera what they normally tell their boys about interacting with cops. Campbell wants her faculty to be on the same page, and aware of how families at Grant may feel the impact of racially charged issues.

“We really need to isolate race in this situation and focus on the things we are doing or not doing that impact the success of our African-American students,” Campbell says.

This year, Campbell handed out to each faculty member a book called The Trouble With Black Boys: And Other Reflections on Race, Equity and the Future of Public Education, by Patrick Noguera. The book is about connecting and building relationships with students of all races. Campbell says the book is discussed during staff meetings. She says while she can’t control what happens outside of Grant, she wants her school to be an environment where everyone feels supported and comfortable.

“Teenagers are coming to terms with their racial identity and what we do in school has an effect on that,” Campbell says. “We’re trying to look at that.”

Caleb Weekly says despite his periodic treatment by police outside of Grant, he feels understood and accepted at school.

“At Grant people know me for who I am. They know what I stand for and what type of person I am,” he says. ◊