It was the first night of spring break 2010. Ansel Carr and his mom had just gotten into another argument. But this one was about to end differently than most. After an exchange of harsh words, pushing and tears, Carr was told to leave the house. It was 10 p.m. and he walked out wearing a light rainbow sweatshirt to keep him warm.

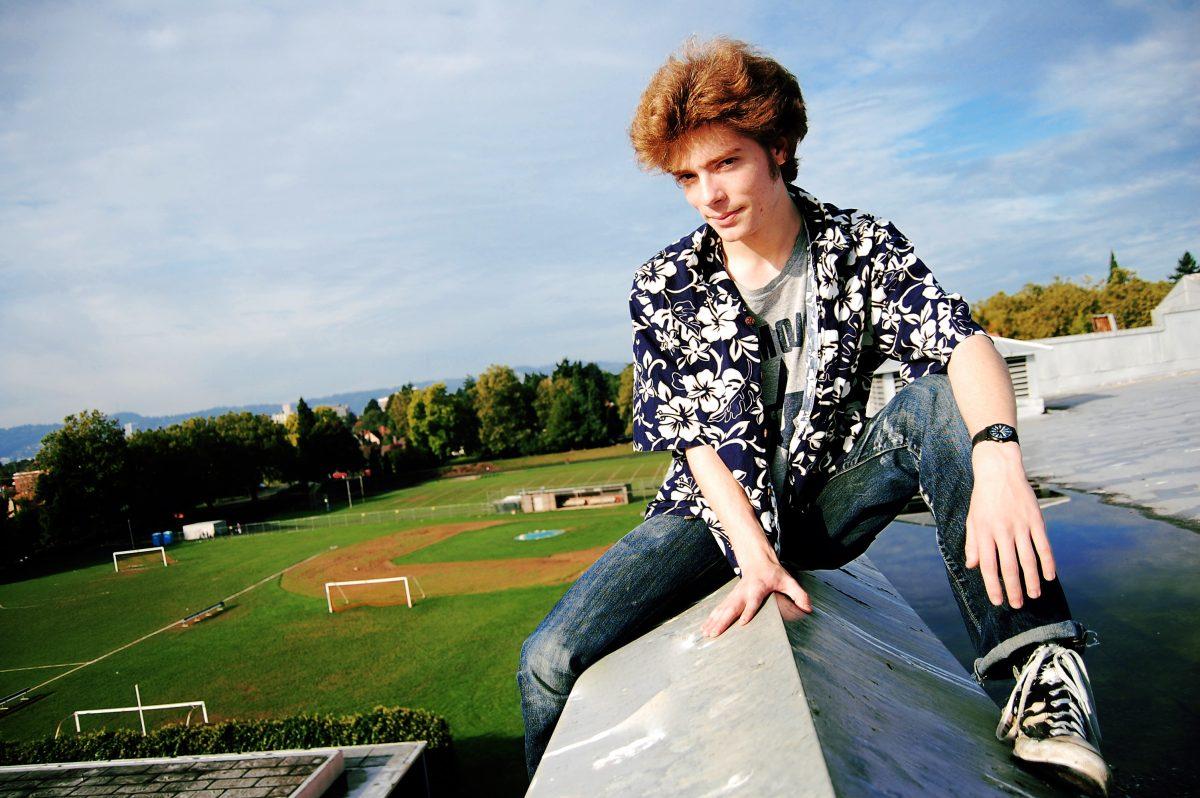

Carr walked the streets looking for somewhere to stay. His dad wouldn’t let him in and it was too late to go anywhere else. So he ended up sleeping on the roof of Grant’s gym.

Carr spent the rest of that week living on the streets. He slept on various school roofs and spent time waiting around in Grant Park. At the end of spring break, Carr simply walked back into his mom’s house, neither him nor his mother said anything, and life went back on as normal, like nothing happened.

In July of his junior year, after his mom got back from a vacation, they had another fight and he was kicked out again.

For the next two months, Carr was without a home. He spent various nights at friends’ houses. But he spent most of his nights sleeping on school roofs. He spent as long as three weeks living on the roof of Beverly Cleary-Fernwood. “It was my couch-surfing, roof hopping bonanza,” he says now.

For Carr, now 17, living outside his house has forced him to make do on his own. Of the estimated 2,000 homeless youth in Portland, many have dropped out of school and live a brutal life on the streets. But Carr is a different type of homeless teen. He has built his own support system and is learning to live somewhat independently. From a young age he’s had to deal with his parents’ divorce, a dad with mental health issues and the pressures of being a teen. And now, Carr struggles with learning to live alone.

“It sucked not having something constant, something to rely on,” Carr says about not living at home. During summer nights, he didn’t have a roof over his head. He used his long, green trench coat or a sleeping bag to stay warm when sleeping outside.

“He’s always been someone who had a really strong idea of what he wanted to do,” his mother Karen Carr says.

She hasn’t seen her son for almost a month now. “I miss him,” she says. “He’s fun to have around when he’s getting along with me.”

Ansel Carr is the oldest of three kids. His sister, Ruth, is a freshman at Grant and his brother, Simon, is in second grade.

“I remember him learning how to climb trees,” his mother says.

He would climb the tree outside, get stuck, ask for help to get down, then run and do it again.

Karen Carr doesn’t remember any big change in her son. She’s seen him develop as someone who didn’t like change, or school. Carr has always had a rebellious side to him, challenging what’s around him and making his own path.

Carr and his mother started arguing when he was in middle school. “It’s when people become more their own person, and less their parent’s child,” he says.

In sixth grade, Carr’s wardrobe consisted of cargo pants, long white socks and a pair of black high-top Converse sneakers. He let his hair grow long and showered infrequently. His signature for the look? A tie-dyed sweatshirt.

“It was easier than picking out an outfit everyday,” he says.

But for Carr, it also was a way to pick his friends, he says now. He knew if he dressed in a way people didn’t like, then those people weren’t worthy of his friendship. In his mind, real friends wouldn’t care how he looked.

As Carr started to assert his personality, he and his mom started getting along less, and squabbling more. Peter O’Brien Dunn, a friend of Carr’s, witnessed several of their arguments.

“The stuff they argued about was not important. Dumb stuff,” O’Brien Dunn recalls.

Carr admits that he sometimes doesn’t have the ability to calm down when he gets into it with his mom. “We have clashing personalities,” he says.

Carr’s parents divorced when he was six, but they still frequently see each other. Because Carr’s father, Damian Carr, is diagnosed with bipolar disorder, he lives in government-subsidized housing. Because of that, he can’t have anyone stay at his apartment for more than twenty nights a year.

Although his father is concerned about him, Damian Carr knows that his son is an independent person and can handle things. “I worry, but he’s pretty good at taking care of himself,” Damian Carr says.

Carr’s father was a lot like his son when he was younger; looking for adventures and pursuing his passions. “I can understand where he’s at,” Damian Carr says. “He has principles and he follows those principles regardless of the consequences.”

That spring break in 2010 was Ansel Carr’s first experience being homeless. Being up high on rooftops provided him some level of comfort. “When you’re sleeping, you want to be somewhere where you won’t be bothered,” he says.

During the long days of the break, Carr spent most of his hours at Grant. Because Carr had left his phone at his mom’s house, it was nearly impossible to contact anyone. “My strategy was to sit around at Grant Park and hope to run into somebody,” he says.

Later that spring, Carr spent a few weeks living with a family member in Southeast Portland. Things didn’t go well one night and Carr and the family member got into a physical altercation. Carr fled and crashed at his dad’s place.

Carr soon went back to his mom’s house. For about a year he lived there pretty consistently except for when he set out for the roofs simply to get away or just for the thrill.

At the same time, Carr randomly decided to drastically change the way he looked. “I had been doing the same thing for six years,” Carr explains. “I wanted change.”

His parents bought him $400 worth of suits. He cut off most of his hair. People barely recognized him. “The attention was non-stop,” he remembers. But after living at his mom’s for a few weeks, Carr felt that home was becoming too strict. He left again.

By living at his friends’ houses, Carr thought he would wear out his welcome. That’s when Aaron “Alf” Fink helped Carr construct a tent on the top of Beverly Cleary-Fernwood.

They used a tarp and cord found on another school roof to make the tent. They gathered a mattress and couch cushions from around the neighborhood. On the first night Carr slept there, it rained. But the tarp worked, Carr recalls.

To stay warm, he slept over the heating vents. He used the open outlets to charge his iPod. Sometimes, he “borrowed” food from QFC or Fred Meyer nearby. He discovered Panera – a place in Hollywood that offers discounted meals to people who are in need. He even worked a couple shifts there to pay for what he ate. And at nights, he would find a roof.

“Everyone has a hobby, mine is climbing,” Carr says. “And some hobbies are more legal than others.” He enjoys the feeling of being up high; it empowers him, and makes him feel successful. “It’s the only way I get that feeling of freedom, it’s the feeling of being above the world, above people, above problems,” he says.

“Half of the challenge is finding the way up,” O’Brien says. Carr and his friends have gotten onto roofs by scaling windows, windowsills and other obstacles or even climbing up a pipe on the side of a school.

Carr has never been arrested for climbing. When police catch him, they ask him how he got up and then tell him to get down.

He sees each climb as a challenge that he is determined to overcome.

“It’s dangerous,” he says. “I like danger.”

As summer came to an end, Carr wanted a roof over his head. So he moved in with Fink and his family where he’s been since the beginning of the school year.

Carr has had some contact with his mom since leaving this summer. They even sat down together to discuss the possibility of him coming home. He didn’t want to give up the freedom he has at the Finks’. Moving back “was not in either of our best interests,” he says.

Although Carr’s father misses seeing his son, he is confident Carr will be OK. “I’m just glad he has a place he can be safe, where he feels comfortable,” Damian Carr says. “They seem to be really good people. They seem to be really good to him.”

Fink’s parents paid for Carr’s cap and gown, bought him some clothing and even offered to buy him school supplies. But Carr didn’t want to accept because he didn’t want to take advantage.

“Being taken in like that, when they have no reason to, it’s mind boggling,” he says.

Although Carr has a decent relationship with his sister, he doesn’t see his brother anymore. “It’s hard. I want to be a role model in his life,” he says. “His brother misses him a lot,” says Karen Carr

Although Karen Carr wants her son to live at home and be part of the family, she knows that he is better off living at Fink’s than somewhere on the streets, or worse. “I feel that he’s pretty safe there,” she says.

Since all this has happened, Carr feels he has moved up in the world.

“I was a nobody,” he says. Now, “I am a somebody.” “There’s a lot of stuff in the world and I’d like to at least sample all of it. We’ll see how that works out.”