The cacophony of basketball shoes squeaking against the waxed gym floor is deafening. Beads of sweat fly through the air as players dart nimbly between each other. Across the court stands a short powerhouse of a man.

His arms windmill wildly, urging the players to pick up the pace. Box out. Turn it UP. Get in him! PUSH IT. The other coaches struggle to get a word in edgewise as the man walks up and down the lines, setting the tone for the game. He’s there to win.

The other team steals the ball and dribbles down the court. The coach watches as they advance toward the point guard – his son – and his eyes emote the challenge: “Just try and shoot. I dare you.”

In high school, Joe McFerrin II was a Grant sports all-star. When internal family issues threatened to lead him astray, the Grant community gave him the support he needed to stay afloat. Throughout his life, McFerrin has been surrounded by strong role models who have guided, supported and pushed him. Today, McFerrin, 45, has become one of those role models, drawing upon his own experiences with mentorship.

He is the president and chief executive of Portland Opportunities Industrialization Center, a non-profit alternative high school organization dedicated to helping at-risk youth. “What I’m trying to do,” says McFerrin, “is figure out the secret sauce that can help kids change in their trajectory to become self sufficient and members of our community.”

Born in 1969 in North Portland, McFerrin grew up in a small yellow house off Vancouver Avenue with parents Sandra and Joe McFerrin Sr. and a younger sister. Joe Sr. was more old-school than his wife. His family – who moved from Arkansas to work in the Portland shipyards – believed in hard work and spending the bare minimum.

Sandra McFerrin’s Chicago roots valued education, politics and fighting the system.

“I had two different worlds,” says McFerrin II. “She liked fashion, he liked saving every dime. She got accepted to law school, he was like, ‘No, you need to raise your family.’”

The difference in his parents’ values granted McFerrin a balanced lifestyle. While his father was at work, McFerrin would sit in the living room under a large poster of Malcolm X and listen to Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” with his mother. Later, it was off to baseball practice with dad.

Sports became the center focus of McFerrin’s life from a very young age. Baseball, football and basketball consumed his time. His father, who valued the accountability, dedication and work ethic that stem from athletics, was McFerrin’s coach in all three sports from age 4 to 13.

“It’s tough when your dad’s always the coach,” says McFerrin, “because you’re always held to a different standard. It wasn’t about getting extra treatment. It was about being the example.”

But McFerrin enjoyed being pushed. Competition was in his blood. And as he grew older, his passion for sports only increased. Soon, it was all he thought about. Whenever he wasn’t at practice, he was playing football at Unthank Park with his buddies. Or playing baseball in the streets in front of his grandma’s house. He’d come home after hours in the sun, with grass-stain battle wounds covering his knees, elbows and cheeks.

In fourth grade, he became more independent, often leaving Beech Elementary midday to go watch high school boys’ basketball games at the Veterans Memorial Coliseum. McFerrin would hop on the bus with his dad’s signature scrawled on the yellow permission slip crumpled in a pocket. Once there, he perched in the bleachers, analyzing every play, taking note of what he would do in each situation, itching for the day when he could be on that court.

McFerrin’s father says: “What was different about Joe was that he was always doing something. He had no ‘free time.’ It was either studying, work or practice.” As soon as he was old enough for the responsibility, the dad taught his son to work.

During the summers, McFerrin worked odd janitorial jobs at his future employer, the community-owned non-profit known as POIC. The school was being run by his grandmother, Rosemary Anderson.

Outside of POIC, Anderson was the cornerstone of McFerrin’s entire extended family. Twice a month, the whole clan would rendezvous at Anderson’s house for a good, old-fashioned get-together.

Amongst his cousins, McFerrin was a leader. Before the group went to explore in their grandpa’s junkyard, they waited for his stamp of approval. If somebody got hurt, they looked to “Little Joe” for help. Having a father as a role model set him apart from his cousins. “In my family, not all the other kids had that,” he says. “I was the one who had the dad who was there, who coached, who spent lots of time. That made me different.”

McFerrin’s natural leadership skills and responsibility were put to the test when he was 10. In 1979, McFerrin’s mother had her first bout with bipolar disorder. One day, Sandra McFerrin was working at her job as an insurance underwriter. The next, she was losing it. Manic and hyper, she’d scream at her husband in a frenzied state. Dark circles formed under her eyes from lack of sleep. Her usual bright demeanor faded.

“Mom went crazy and nobody knew what to do,” McFerrin recalls. “I was like, ‘She’s trippin,’ man. My mom is trippin.’”

McFerrin watched as his mom quickly became someone indistinguishable from the mother that he knew. “One of the things I will never forget is when … she would walk me down the street and have me go up and knock on people’s doors and she’d be standing out there, talking to herself,” he remembers.

For the next 20 years, she would be in and out of hospitals and psychiatric wards. McFerrin’s little sister gradually started living with their grandmother as their parents’ relationship tensed.

“I was scared because this was real life. This wasn’t: ‘These kids think they’re hard.’ This was real.” – Joe McFerrin

With his dad working three jobs, McFerrin, who’d begun attending Ockley Green Middle School, learned to take care of himself, taking over household chores his mother normally performed. Cooking. Cleaning. Running errands.

“It’s a mental shift,” says McFerrin, “when you’re used to your mom taking care of you, to when you have to be more concerned about your mom.”

As Sandra McFerrin descended further into her mental illness, her son’s only outlet remained in sports. When the time came, he decided to use his aunt’s address to enroll at Grant, where the sports programs were most appealing.

The newness of the experience excited him. He recalls: “I was being exposed to more socio-economic groups. I had never been around kids that had the resources to just throw parties at their houses and drive cars.”

He made friends quickly. Paul Marrs, a friend since middle school, says that McFerrin was a genuine person. “He was able to speak with people that he’d never met before, from all walks of life,” says Marrs. “He was not afraid of being Joe.”

“Everybody knew who he was,” says Lisa McFerrin, 47 – previously Lisa Harwell, now his wife. “He was just charismatic, kind of cocky and real talkative.”

The two met through her brother, with whom McFerrin played baseball and football. By McFerrin’s sophomore year, they were steadily seeing each other.

“I think it was a trip for her because a) I was younger, b) it was biracial and c) I was a pretty popular dude even as a sophomore,” says McFerrin.

By then, he was the starting varsity second baseman for the baseball team and the starting varsity point guard in basketball. He threw himself into sports, trying to escape the chaos of his home life.

But he couldn’t keep his troubles at bay forever. His mom started showing up at games. In the crowd she was on her feet, fists raised, spit flying from her mouth, screaming her son’s name with an intensity that attracted alarmed looks like a magnet. When team members and coaches approached him about it, he shrugged them off: “She’s just sick, man, I don’t know,” he told them.

“I think that people actually knew that it was killing me,” he says. “I kept the persona up. ‘I’m the star athlete, I’m Joe McFerrin. My mom’s over there acting crazy now but I’m Joe McFerrin. She’ll be alright, that’s just her.’”

Instead of pressing him further, the Grant community surrounded McFerrin in what he calls “indirect support.” He was able to let his walls down around a couple of teammates facing similar troubles at home, and he credits this outlet for managing his stress.

His speech teacher maintained high expectations and held McFerrin accountable, challenging him to write speeches outside the world of sports and making him redo the half-baked ones. While other students disliked the teacher’s strict standards, McFerrin appreciated them. “What it said to me was that she cared,” he explains. “Some teachers, they don’t want to push. They care about you, but they’re not willing to take that risk to really challenge you and confront you about your performance and output and effort.”

On the basketball court, the pressure didn’t hurt his performance. “My whole mentality would be to go in and establish the fact that I am the hardest worker,” he says. “I don’t care if you don’t like me. I’m not looking to be liked. I’m looking to be the best. … Nobody’s going to outwork me.”

Lisa headed to college his junior year, and McFerrin dove even deeper into sports. In 1986, he led the Generals basketball team to a state championship, making the two winning free throws of the championship game. In 1987, they made it to the championships for the third year in a row, but came in second. After the blur of senior year, McFerrin’s sightline shifted to college ball.

In the fall of 1987, he moved to Palm Desert, Calif., to play point guard for College of the Desert. There, “I got caught up in the fun side of college and neglected my studies,” he admits. “I think part of my struggle in school was that I didn’t have that mentor.”

Although he was in his basketball prime, partying replaced studying, golf trumped class and his academics collapsed. “I was letting myself down,” says McFerrin now.

He turned it around his third year by making a point of going to the library to study straight after class instead of going back to his apartment to kick it with his buddies. He wasn’t playing ball. “I learned to treat school like work,” he says.

It’s the lesson McFerrin now uses to help steer POIC students in the right direction. “I use that when I talk to kids about making good choices,” he says.

After getting his associate’s degree (it took him an extra year), McFerrin went to San Francisco State to continue playing ball while starting on his bachelor’s degree. In early 1990, Lisa informed him she was pregnant. McFerrin then had a choice to make: hold onto one more year of his dream or begin raising a family.

“We were just kind of forced to grow up fast,” says Lisa McFerrin. She raised their daughter, Alexandria, alone for eight months while McFerrin finished up his second year at San Francisco State. When he returned to Portland in 1991, “he was angry,” says Lisa, “because he was home and he really wanted to play basketball for a long time, and he had to cut that short.”

While struggling to cohesively parent Alexandria with Lisa, McFerrin finished his undergraduate degree in political science at Portland State University. He and Lisa got married and bought McFerrin’s parents’ old house. But it wasn’t until McFerrin began building playgrounds for Morgan Construction that he began his transformation into true adulthood.

Company owner George Morgan taught McFerrin about more than just managing a business. “We talked about how to raise a family,” says McFerrin. Morgan’s mentorship was pivotal. “I had a person I could just talk to every day about being a young husband, a young father. So I got a lot out of that.”

But construction didn’t satisfy his needs in the long term.

One day in early 1995, McFerrin was at POIC High School, asking to borrow the car from his grandmother, when the director of education, Sam Kelly, approached him about a full-time job opportunity. Kelly wanted McFerrin to be a counselor at the school.

“He tapped into my background as an athlete and my sense of connectedness to the community and he basically challenged me to take a risk,” says McFerrin.

He couldn’t resist a challenge. McFerrin began working on the front lines for POIC, evaluating transcripts, meeting with students and family members to address disciplinary actions, breaking up fights.

“I was scared,” says McFerrin. “I was scared because this was real life. This wasn’t: ‘These kids think they’re hard.’ This was real.”

“I don’t care how bad a student has done in the past academically…I’m gonna hold the bar high.” -Joe McFerrin

McFerrin remembers having to grab a student twice his size in a bear hug from behind in an attempt to rip him from a fight. “He was so strong… He was bouncing me off the walls and off desks and off chairs and I was just holding on. I was just like, ‘I can’t let go. Because if I let go, this kid is going to kill this other kid with his bare hands.’”

As McFerrin adapted to the volatile environment, Kelly grew to be one of his strongest influences. “He taught me how to be very clear and very direct with people about what you need and what you want,” says McFerrin, “and he taught me that I could do a lot more than I was doing. Period.”

Kelly strongly encouraged McFerrin to earn his master’s degree. McFerrin was working full time and just beginning to raise his second child, Joe III. He didn’t believe he could pull it off. But Kelly didn’t take no for an answer.

“So I jumped off the cliff and he was right,” remembers McFerrin. “He showed me how you weave your work into your life so that it becomes almost one.” This is a lesson McFerrin works to teach kids today. Just as Kelly continued to push him, McFerrin challenges POIC students to aim high.

“I don’t care how bad a student has done in the past academically,” McFerrin says, “I’m gonna hold the bar high and have high expectations. I’m not gonna be OK with a lack of effort.”

After three years of night classes, McFerrin finally earned his master’s in public administration. Using his new skills, McFerrin became the rainmaker for POIC, bringing in more revenue than the organization had ever seen. He brought in community contracts, raised the enrollment, and secured $1.3 million from a piece of the Work Force Development contracts. Under his leadership, the once ragged school “came down off the hills of bankruptcy” and established a larger presence in the community.

John Stilwell, McFerrin’s high school basketball coach at Grant and current POIC Board Chair, says McFerrin works best under pressure. “Whenever you work in a non-profit, you’re always understaffed, under budget, you’re always working from behind. And that’s something he’s phenomenal at,” Stilwell says.

Rosemary Anderson retired in 1997, and the school was renamed Rosemary Anderson High School in her honor. When Kelly retired in 2003, he left the role of president and chief executive to McFerrin. His work shifted from working one-on-one with students to doing more behind the scenes work, like shouldering the massive undertaking of establishing a second campus for students far away in East Portland.

But McFerrin refused to let his high-up position prevent him from helping kids directly.

Darcelle Hicks, a graduate of RAHS in 2008, developed a strong relationship with McFerrin her senior year. He would seek her out, bring her into his office and work with her to draw out a roadmap on the large notepad he always keeps by his desk.

“Let’s talk about what your plans are, Darcelle,” he would say. “You’re getting ready to graduate. Where do you see yourself in the next two years? Where do you want to be?”

Hicks recalls feeling honored that he took the time. “He has a lot of people that he has to carry, not only students but the staff, all of the partners,” she says. “His role is like the heart of the whole operation and so if he’s not on his A game at all times, the

students will fall or the staff will fall or the whole business will fall.”

For McFerrin, the students are the focus. He makes sure they know his doors are always open if they need support or extra resources or just have questions.

“He always says: ‘If you call me and I don’t have the answer, then I’m gonna reach out and find someone who can get the answer for you,’” says Hicks.

When she got a job at Portland General Electric, McFerrin celebrated with her. “He gave me a big hug, he just looked at me (and said): ‘Wow, girl…Wow,’” Hicks recalls.

Lisa McFerrin says: “A lot of people can get satisfied in their job and they can just do it and go home. But Joe’s constantly looking to grow it. It’s not like a nine to five job at all. It’s not something he puts on the shelf. It’s always in his head.”

With all the time he spends on work related things, you’d think McFerrin wouldn’t have much time to spend with his own family. But that’s not the case. His family still gets together on holidays to catch up. His mom is now mostly stable and they visit regularly.

And he has made a point of being a strong role model for his own three children, just as his father did for him. He coached his son in basketball, football and baseball, and Joe McFerrin III recognizes the difference his dad’s efforts made.

“I felt like I was gonna be taken care of. And I was going to learn,” says the 19-year-old McFerrin. “Anything I struggled in, he was always there to push me harder and help me out.”

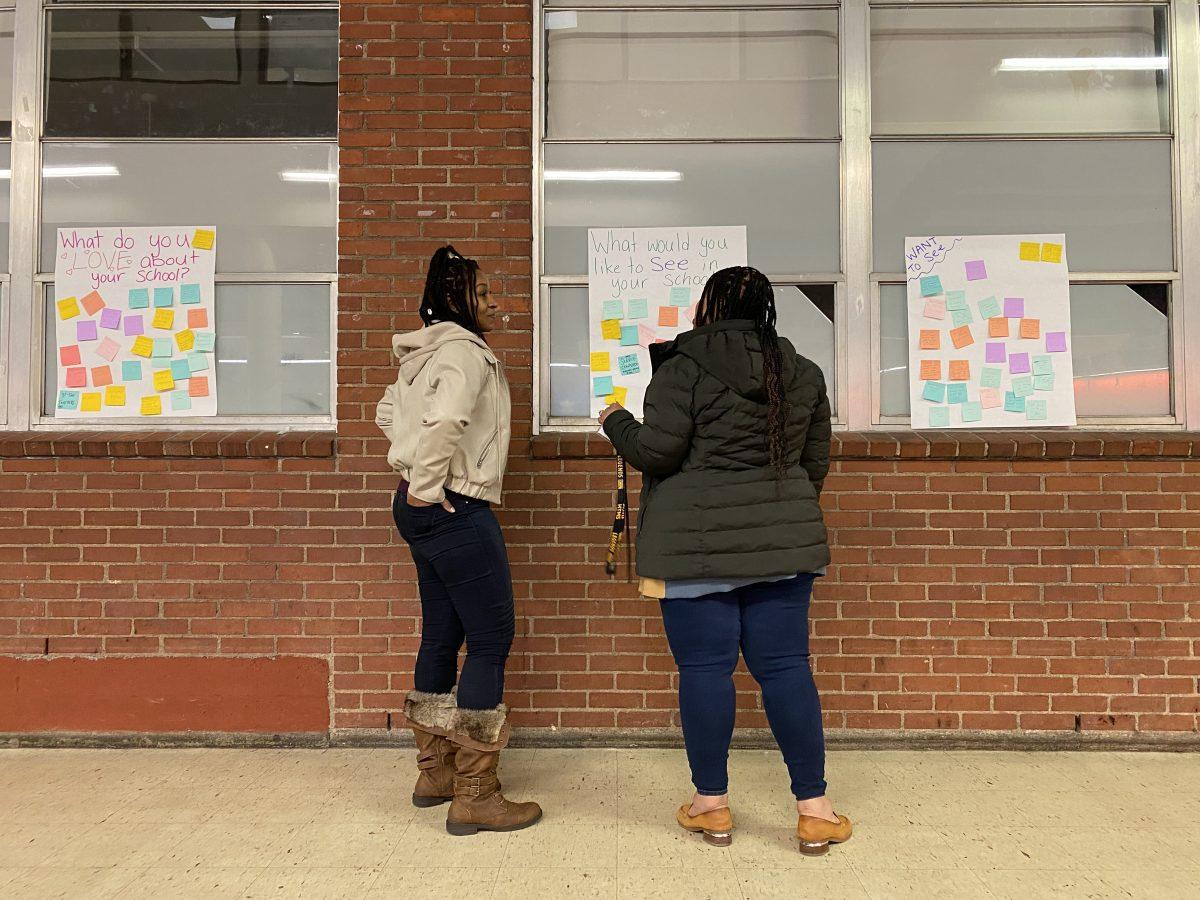

A door swings open under the moss-encrusted awning that accents the small concrete building on North Killingworth Court. Two teenage boys exit, a basketball nestled in one’s tattooed arms. It’s 12:10 p.m. – lunchtime at Rosemary Anderson High School.

Inside the school, things are buzzing. Students mill about and congregate in the stairwells, some toting backpacks and textbooks, others sporting bruises and baby bumps. “There’s a lot of energy in our building,” says Bob Brandts, the school’s director of operations. “It’s very vibrant. Never boring.”

A string of shouts interspersed with expletives can be heard from behind a closed wooden door by the front desk as Joe McFerrin tries to calm down a riled student within. An hour later, the student exits the room with his attitude much improved. McFerrin also emerges, exchanging raised eyebrows with the young alumna manning the front desk under the large portrait of the school’s namesake.

This event was not planned in the day’s agenda, setting McFerrin back in his meetings, phone calls and emails. But he handles the roller coaster atmosphere with grace, drawing upon his experience from dealing with his mom’s mood swings.

“We want to help kids work through their issues. So we encourage them to bring their issues to us,” McFerrin says. But that means “it’s a war zone every day.”

McFerrin straightens up, shakes out his brown suit coat, adjusts his tie, and reassumes his seat in the black rolling chair in his office. He moves the freshly drawn game plan web from his desk and picks up the phone, checking his watch. He’s going to be home late tonight. ♦