Siena Loprinzi digs her hands deep into the bowl of creamy cookie dough, kneading out the lumps to perfect her signature cookies. She places them in the oven and chooses a song on her playlist while she waits.

It’s a friend’s birthday and Loprinzi – a junior at Grant High School – always makes a point to ensure that someone isn’t forgotten on such a special day. “I try not to miss a birthday,” she says.

Later that day, Loprinzi heads out the door and drives a few miles to Grace Memorial Church in Northeast Portland. Every two weeks, she volunteers to feed the homeless at the church’s Friday Feed.

“Is there a vegetarian option?” asks an unshaven man in tattered clothing. He’s a regular at the event and Loprinzi chats easily with him as hands him a plate piled high with vegetarian spaghetti. She maneuvers through the maze of tables, serving a hearty dinner to more than 75 needy people.

The scene is like many in the life of the 17-year-old who is president of Grant’s Octagon Club, an organization that pushes volunteerism. She has spent much of her teen years trying to comfort others. She likes to “pay it forward,” taking the good will she’s been given and spreading it to others.

Her drive is rooted in a past marked with being a target. As a child, Loprinzi was bullied so badly that she had to repeatedly change schools. “School has never been easy,” she says. “I have gone to 10 schools, and I have been bullied at each one in a different way.”

Coupled with a learning disability, Loprinzi has to work harder than most students to keep her grades up and her head above water.

“She is such an amazing daughter,” Loprinzi’s mother, Jennifer Beighle, says. “I feel like I have won the lottery. She works incredibly hard; she’s nothing like the teenager I was.”

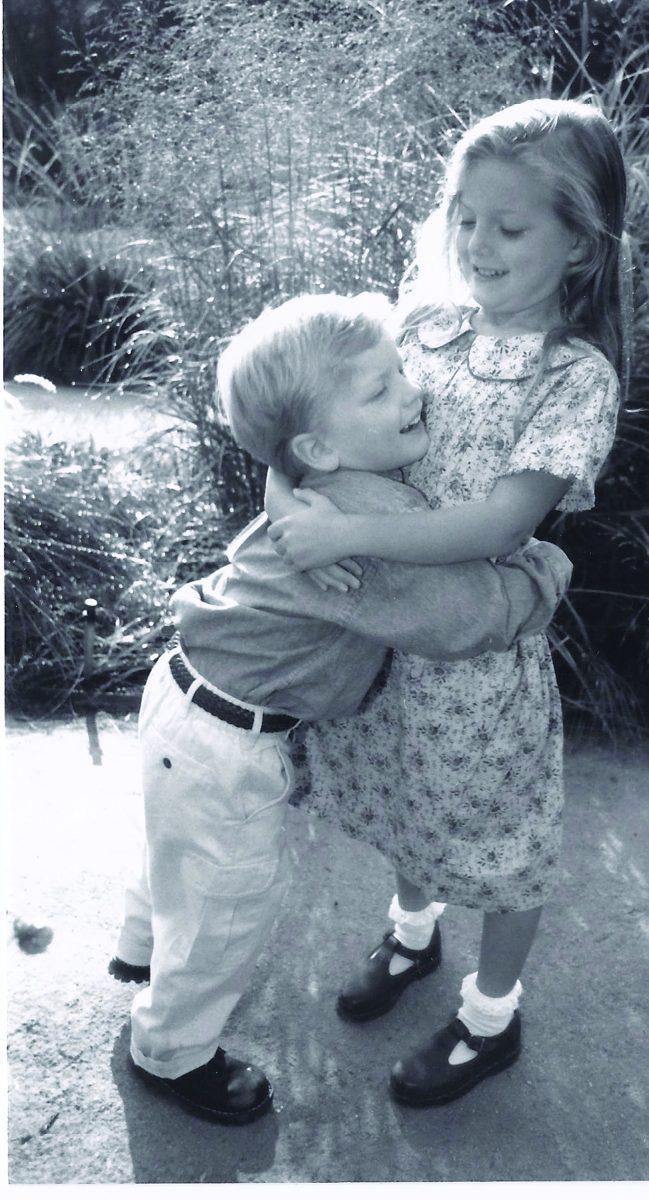

Loprinzi was born in Portland but her family moved to Colorado because they wanted to raise Loprinzi there. By the time Loprinzi was 11 months old, her parents divorced. Her father remarried when she was four.

Beighle says her daughter had to adapt to a different family dynamic. It wasn’t an “ideal situation for Siena,” she admits. “I think it has made her more resilient.”

As a young child, Loprinzi was very sure of herself. Beighle recalls a friend giving her a book called “Parenting The Strong-Willed Child.” She would wear her pajamas to school no matter how hard her mother tried to convince her to wear clothes. “It was a good sign that so early on Siena had a strong sense of herself and wasn’t going to be easily influenced by peer pressure if she felt strongly otherwise,” Beighle remembers thinking.

According to Loprinzi’s father, Phillip Loprinzi, “Siena had a heart of gold and was always kind to those with less fortunate ability.”

That changed when the bullying started. It was in kindergarten when Loprinzi remembers the time a girl choked her to force her off the playground. “I got to the playground first and she got really mad,” Loprinzi recalls.

She couldn’t understand why her classmates constantly targeted her. But the bullying continued. “In second grade, my teacher told me that I wasn’t smart,” Loprinzi says. “That was awful.”

When Loprinzi stayed at her dad’s house, she didn’t get along with her stepmother so she felt like she never had a break from confrontations.

At school, the other children made fun of her because it took her longer to finish math tests. They chided her when she was asked to read something and did it slower than other kids.

“The bullying completely changed her personality,” Beighle remembers. “She went from this vibrant, funny child to one that cried every day before school.”

Beighle tried to approach school administrators about the issue but says she never received much help. The bullying continued. “It was heartbreaking,” Beighle says.

So Loprinzi’s mother changed schools. At her new school, the little girl regained her sense of self and developed what Beighle describes as a “deep conviction that she would not allow anyone to treat her like that again and that she would not allow any of her classmates to mistreat” one another. “She always treats others with respect and kindness even if they do not initially treat her that way,” Beighle says.

By middle school, Loprinzi and her mother had moved to Montana. She remembers not liking the lack of diversity there. She said a lot of the kids she met were narrow minded.

“I didn’t know anyone that was gay there. I only knew one African American,” Loprinzi recalls. “I just wanted to be myself. I went into a depression. I didn’t really have any friends.”

She changed schools again but things didn’t get any better. She made some friends but says they didn’t treat her well at all. “The whole time I was in Montana, I was having a terrible time,” she says.

Montana wasn’t working out for her mother, either, so they moved to Portland and Loprinzi soared.

When Loprinzi first attended Grant as a ninth grader, she was nervous. But she made friends quickly. “There was no drama,” she says now. “It was great.”

Emily Olson was in Loprinzi’s freshman community and remembers her gear towards academics. “She was always working so hard in class,” Olson says. “She is a great person and I am so happy that we are friends.”

Today, Loprinzi dives into school. She takes a load of challenging classes and has to work particularly hard because of her learning disability. Two years ago, Loprinzi was diagnosed with comprehension disorder, a learning disability that makes schoolwork harder for her. “I comprehend things twice as slowly as other people,” says Loprinzi, who kept her learning disability under wraps for a long time. “So I have to work twice as hard at school.”

Her mother marvels at the progress her daughter has made. “Siena is very driven and has high standards for achievement,” Beighle says. “It has been a challenge to watch how much effort and time she has to put into her homework to get the grades she wants.”

Loprinzi spends much of her time giving back. Last year, she interned for the Children’s Book Bank, a non-profit organization that donates books to children in need. She also serves as the Grant student representative for the Superintendent’s Student Advisory Council. “I went into the PPS building and took the elevator up to the floor, opened the big doors and was scared to go in,” she says. “I heard of schools I didn’t know that I existed. Learning about the different schools and their situations makes me want to help them out.”

As one of the four finalists for princess on the 2012 Grant Rose Festival Court, Loprinzi plans to share her experiences with bullying and having a learning disability.

If her experience helps someone else who is facing the same adversity, then it’ll be worth telling her story.

“I just love helping people,” she says. “I am so passionate about life and everything it has to offer.”