Three weeks after her brother’s unexpected death in 2008, Madeleine Terry flew across the country to compete in the Synchro Age Group Nationals. It was the week of his birthday and the only place she wanted to be was home in Portland with her family.

Her cell phone had broken. She was disconnected from her parents. And she felt alone during one of the toughest times of her life.

Then Terry, who was 14 at the time, got her placement draw in the synchronized swimming competition. Number 11. That was Finn Terry’s favorite sports jersey number and his age. Coincidence? Not to her. When something like this happens, it’s “when I know Finn is with me.”

Now a senior at Grant and a nationally-ranked synchronized swimmer, Madeleine Terry finds solace in the water. It’s been four years since her brother drowned while on a boating trip on the Clackamas River with the Boy Scouts. Losing him is something the closely-knit family will never adjust to.

But Terry is at peace. “The reason I am as committed to everything I do is because of Finn,” she says. “I tried to find the best of him and show it in myself. I have always wanted to have the strength to help people, and since my brother died it’s become a necessity rather than a dream.”

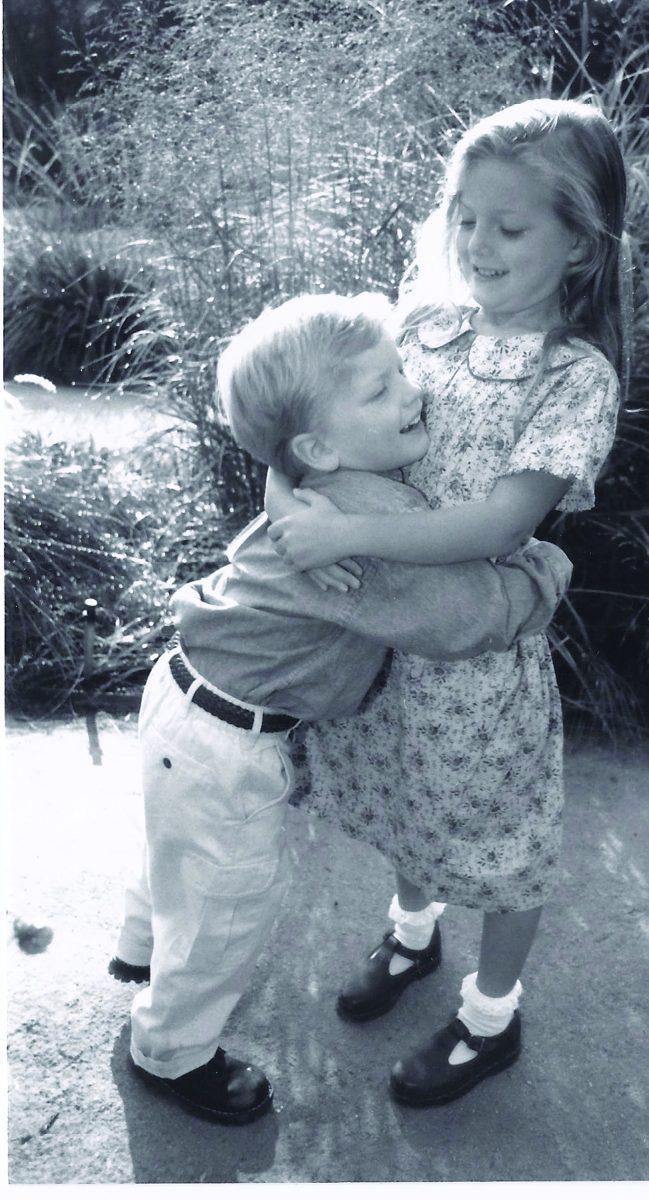

Terry, the oldest of four siblings and the only girl in her family, was an adamant child. She remembers the day Finn was born. “He was perfect and tiny and cute like one of my dolls,” she recalls. “I knew from that moment on he was going to change my life.”

Terry and her brother were inseparable growing up. Their childhood days were spent on Slip ‘N Slides, running through sprinklers and making up endless games. Every time they went to a restaurant, they asked for extra spoons to balance on their faces – their goal was to break the world record.

“When I learned to talk, everybody listened to me for some reason except for Finn,” Terry remembers. “He intrigued me because he never did what I expected him to.”

When Terry was 7, her mom registered her for synchronized swimming at Grant Pool and Terry dived headlong into a sport that would define the next 10 years of her life. It’s a graceful sport with sparkly costumes, refined athleticism, and a combination of swimming and dancing.

Her love for the sport endured a year at a decrepit pool in North Portland with teammates twice her age and another at the Tualatin Hills Aquatic Center. Her drive earned her an athletic scholarship to the Multnomah Athletic Club and a more competitive team with nationally-qualified coaches.

Terry was in her element, practicing more than 20 hours a week. In her first year, her team placed 17th nationally. They placed in the top 10 every year after that. She traveled as far away as the East Coast and Hawaii to competitions.

But even with such a time commitment, Madeleine’s connection with Finn remained. They would talk for hours, often sitting on the couch wrapped in old blankets, discussing crushes and their dreams for the future.

Terry was helping her mom sell snacks at another brother’s baseball game when they got the call. All her dad could tell them was they needed to come home. It was about Finn. “I thought he had just broken his arm or something,” Madeleine Terry remembers. “I just hadn’t realized yet that it was possible for an 11-year-old to die. That you can be the best swimmer and still drown.”

She remembers everyone crying and people bringing food to her house day and night. The pool became her sanctuary. At first, the idea of getting in the water terrified her. But once she was back, it just felt right. It was the only place where she could escape the reporters, the hushed talk of dangerously high water levels and a rescue attempt gone horribly wrong.

Terry kept reminding herself that “just because his life ended didn’t mean he wanted me to stop mine. I would be doing a disservice to him because then it would be like two lives ended.”

Pam Terry draws strength from her daughter. “She is inclusive, empathetic and has the strength of character of someone much older,” Pam Terry says. “She has faced adversity but it has pushed her forward.”

Madeleine Terry has changed her focus now. She spends a lot of time in the pool, but her perspective is different.

“Finn really affected her a lot,” says Hannah Morton, Terry’s teammate and best friend for eight years. “It was more live each day to the fullest after that.”

Terry doesn’t think about swimming all the time. She’s reached out and thinks about becoming a doctor because she wants to help children.

Recently, she was volunteering at a camp for children with cancer when a little boy named Sam came up and sat down next to her. He was five and battling leukemia.

“He stopped and stared up at me with a look of worry and sadness in his eyes and said six words I will never forget: ‘I am too young to die,’” she recalls. “In that moment, I knew I needed to help these kids in some way greater than just playing games with them at camp. That’s why I want to help kids like Sam beat the odds.”

She wants to become a pediatric oncologist. She is applying to Stanford, University of Oregon and several other West Coast schools because she doesn’t want to be more than a quick flight away from home. “My future has been changed a lot,” she says. “Most people stay in the world of synchro and that’s all they do. I want to live more. That wouldn’t be possible if I was traveling the country to train 8-10 hours a day in the pool.”

She still competes and has a rigorous schedule in the pool – practicing five or six days a week. She’s heading to Arizona in April for the U.S. National Synchronized Swimming Championships. But she’s gained perspective.

“Finn’s life ended, so I go out into the world everyday with the goal of doing something that would make him proud of me,” she says.

“It is now important for me to live my life to the fullest because he will never have the opportunity to live his.”