Aleah Zimmer sits at her kitchen counter, snacking on some shredded cheese. She texts her sister, who is on the way home from a job interview, with a food order: pizza and Oreos. Zimmer, 17 and a Grant senior, is hungry after a long day and she wants to eat something substantial.

Four years ago, such an interaction wouldn’t have been possible. That’s when Zimmer was diagnosed with bulimia and anorexia, eating disorders that can have dangerous outcomes when left untreated.

“Looking back on it, it kind of freaks me out,” Zimmer says now. “It’s hard to believe I had that destructive of thoughts.”

Zimmer isn’t alone. According to the Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders Organization, roughly three out of every 100 American women suffer from bulimia – an illness where body image and other factors push someone into binge eating and purging. About one of every 100 suffer from anorexia, characterized by a relentless pursuit of being thin to the point where someone’s health is seriously harmed.

According to the Mayo Clinic, “modern Western culture tends to place a premium on being physically attractive and having a perfect body. Even with a normal body weight, teens can easily develop the perception that they’re fat.”

Michelle Watson, a counselor in Tigard who focuses on eating disorders, says those suffering from eating disorders are often “beautiful, talented, amazing, gifted girls…but the lies in their heads are so loud that they’re a burden or ugly.”

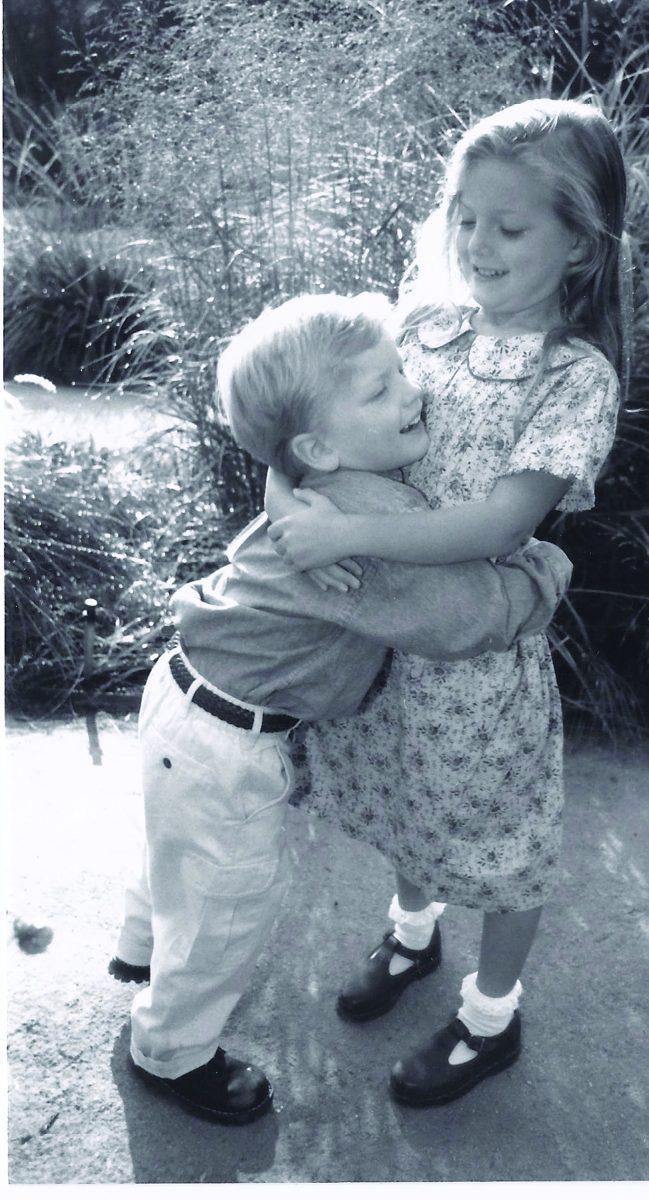

Zimmer wasn’t always that way. She was born in 1994, the younger of two children. When she was two years old, she was given the nickname “Wild Thing” because of her fearless demeanor and her love of performing. Zimmer and her sister put on plays on the family’s deck, using a shower curtain as the stage curtain. In third grade, she put on a production of “The Last of the Really Great Wangdoodles,” based on the book by Julie Andrews, casting her friends in the roles.

In fifth grade, the teachers at Alameda Elementary School put on a production of Shakespeare’s “The Comedy of Errors.” Zimmer chose the role of Dromio, a buffoonish clown character, over the romantic lead.

She and a friend dreamed of being famous actresses and planned out how they would walk down the red carpet at movie premieres and the Academy Awards. When Zimmer was in sixth grade, she visited New York City for the first time. Her family walked past an expensive apartment, and she turned to her father and said: “Some day, I’ll live there as an actress and you’ll get to visit me.”

Her father, Rick Zimmer, a former high school theater teacher and artistic director at Mount Hood Community College, often saw kids go to New York to try to make it as actors and end up not hitting it big. But his maxim: “If there’s something you’d be happier doing, do it,” encouraged his younger daughter to follow her dream.

What Zimmer and his wife didn’t know was the unhealthy secret lurking behind their wild child. Zimmer had a problem with her image and food was the enemy. She was heavier than most of her friends, and she didn’t know of any actresses that were on the heavier side. “I looked at all these famous actresses and they were all frail, skinny women,” she recalls.

Elementary school bullies didn’t help her self-esteem. Kids told her that she was too fat to run. Ingrained in her memory is the time a boy told her that if she cut all of the fat off her body, she could feed an entire Third World country.

“Grade schoolers were just vicious,” Zimmer says. She tried to not let it bother her too much, but she would often run away and cry when people taunted her.

In fifth grade, Zimmer went on the South Beach Diet. Her parents were OK with their daughter’s attempt to eat healthier, but they didn’t foresee how severely she would take it. “There was no room for messing up or having free days,” Zimmer says. Later that year, she tried eating foods without sugar and lost weight quickly. In sixth grade, she started working out “like crazy,” she recalls.

She went through a growth spurt, which more evenly distributed her weight and made her happier with her body. By seventh grade, she thought less about food and losing weight. But a year later, she gained weight again. “That freaked me out,” she says. It put her back into the negative mindset.

She learned to make herself throw up after eating and severely cut back her food intake. “I just wanted to be thin,” she says. “I always had a goal weight and I would reach my goal. But I always wanted to lose more. I never reached happiness.”

When Zimmer entered high school, she compared herself to other girls more and more because of the new environment. She had always compared herself to others, but the difference in body types between freshmen and seniors made the comparisons even more intense. “I was thinking about all these girls who were prettier than me and I thought the only way to get as pretty as them was to lose weight,” she says.

That’s when Zimmer turned it up a notch when it came to losing weight. “I decided that I wouldn’t eat all day one day, and then I did it for two days,” she says.

The pattern continued. When Zimmer was eating the least, she was cooking the most. She became obsessed with recipes and the Food Network, making extravagant four-course meals and preparing lunches for her family. “I felt like touching food and smelling food and creating food was almost as good as eating it,” Zimmer says now.

Her parents had some suspicions but were reluctant to bring it to the forefront. “I did not really want to name it,” says Zimmer’s mother, Pat. “I didn’t want to say the words: ‘Is this an eating disorder?’”

Once, the family went to a fondue restaurant for Pat Zimmer’s birthday. Her daughter prepared everyone’s food for them, taking a few bites here and there to make it look like she was eating as much as everyone else. “She was very discrete,” Pat Zimmer recalls.

But it was harder to cover up that she never ate the lunches she took to school or the dinners her mother made after Zimmer returned from the gym. Zimmer would avoid hanging out with friends if she knew they were planning on going out to dinner.

Finally, mother and daughter clashed about Zimmer’s eating habits. The arguments were exacerbated by the fact that not eating made Zimmer cranky.

“I knew I had a problem,” she says. “But I didn’t want to quit. There’s always that voice in your head. It gives really hateful remarks, but it’s your friend. Like, we’re working toward this goal.”

It was in February 2009 that Zimmer’s mother decided to act. She took her daughter to the doctor. “My vital signs were in the toilet,” Aleah Zimmer remembers.

The doctor told her that when she was lying down, her heart rate was slow. If she stood up, the pace quickened so much that it put her at risk for cardiac arrest. He told her that she had an eating disorder and that she needed to go to the hospital immediately. Pat Zimmer checked her daughter into treatment that day.

Zimmer lived under a strictly timed schedule while at the hospital. Attached to an IV and a heart monitor, she was only allowed to leave her bed to go to the bathroom a few feet away. Even that required her to be wheeled in a wheelchair. Eventually, she was allowed to go on “outings,” where she was wheeled around the hospital for a few minutes before being let outside.

Even though Zimmer had to eat regularly while at the hospital, she found her stay relaxing. “It was hard the first meal,” Zimmer says. “But after that I would get excited for mealtime. I think it was because I was taken out of my regular routine.”

After ten days at the hospital, Zimmer was released. She started going to school again right away and told everyone she had been in the hospital for a heart problem. “People knew more than I gave them credit for,” she says now. “People tell me now that everyone knew, but I didn’t know that.”

When Zimmer was released, she was told she had to eat regularly and was forbidden to exercise. “When I got back home I thought I could go back to not eating,” Zimmer says.

But it wasn’t so easy. Zimmer had to eat planned meals with her parents every day. She even had to come home from school for lunch. “It was just so hard to finish a meal,” she says.

Once during a family dinner, Zimmer broke down and bawled so hard that her sister had to leave the room. Her mom tried to calm her, but it didn’t work. Her dad took her to the den with her dinner. “I would take a bite, then wait 15 minutes, then would wait another 15 minutes between bites,” she recalls.

It took her two hours to finish her plate of fish and vegetables.

She followed the prescribed meal plans, but worked out in her room at night and sneaked out of her house to go running. She began to throw up her food more and more. It got to the point where Zimmer’s parents had to remove the door from her bathroom and they had to sit with her for two hours after every meal.

She still attended weekly outpatient program sessions with a physician, therapist and a nutritionist. It was the check-ins that eventually helped Zimmer overcome the disorder. “There was this expectation of eating what I needed to eat and gaining weight, and there was no escaping that,” Zimmer says.

Zimmer transferred from Grant to Cleveland High School for her sophomore year so that she could be at the same school as her best friend Martha Brown. “Martha ate lunch with me, and even if we ate lunch with other people, she would always notice if I was eating,” Zimmer says.

Whenever Zimmer would hang out with Brown, Zimmer’s parents would tell her friend to encourage their daughter to eat. “It was always awkward for her to be the voice of reason,” says Zimmer. But looking back, “I appreciate that.”

Although these factors helped Zimmer, she attributes her ability to get over her eating disorder to increased maturity. “I got tired of inflicting this pain on myself and trying to reach this standard that I wasn’t going to reach,” she says.

She stopped going to her outpatient program in the middle of sophomore year because she was eating regularly and was doing well with counseling.

The summer after her sophomore year, Zimmer went to Honduras with her church group to rebuild houses in a small village that was destroyed by a flood. Food wasn’t always readily available in the village. She calls the people she met there “some of the nicest people I’ve ever met. They don’t take things for granted.”

That’s when Zimmer decided to approach life in a different way. “I started accepting what I eat—that I need to eat,” she says. “I lost the power to restrict myself. There were still days when I thought ‘I should go back into it,’ but I wasn’t always thinking about food. It was refreshing.”

Zimmer transferred back to Grant last fall for her senior year and has found her niche in the theater department, having performed in the “One Act Festival” and “Twelfth Night.” Last week, she was cast in “Hairspray.”

Her passion, though, is helping those less fortunate than her. Last spring, she worked at Phame Academy, an acting program for adults with Down’s syndrome. The people she worked with there are “some of the happiest and most genuine people you will ever meet,” she says.

Spending time with those less fortunate has taught Zimmer new life’s lessons. “There are definitely days when I wish my clothes fit differently or that my face looked different, but I’ve come to realize that that’s natural,” she says. “I’ve learned to breathe through it and not go through self-destruction.”

She realizes that her story could help others because “it’s nice to know that you can get over it, and find what you love instead of excelling in an eating disorder.”

She plans on giving acting a shot for a year after she graduates high school, traveling to New York and California. She wants to see if she can make it big. “But if I can’t,” she says, “I’ll open a home for adults with Down’s syndrome and incorporate theater into that.”

Whatever happens, Zimmer knows what life will be like for her. “When I wake up in the morning, I wake up happy,” she says. “It’s refreshing. It’s nice.”