It’s 12:32 p.m. and Brian Hanson stands on the corner of Southeast Holgate Boulevard and 79th Avenue, waiting for the No. 17 bus. When it arrives, he finds a seat and opens up his Bible. Hanson’s daily commute to Grant High School, where he works nights as a school custodian, takes about an hour.

“I don’t mind the ride,” he says. In fact, he enjoys the quiet as he reads.

When the bus arrives at Northeast 24th Avenue and Thompson Street, Hanson gathers his belongings and walks to 33rd Avenue and around the park. He follows the path to the door above the Grant cafeteria, just minutes before his 1:45 p.m. shift begins.

“If I didn’t like the class, I didn’t go.” -Brian Hanson

Hanson has been a custodian at Grant since just before the end of last year. Long after the students leave, Hanson and a team of custodians clean up the school in order to keep things running smoothly.

He openly admits the custodial field isn’t a strong career choice. But after a long stretch of unemployment, Hanson didn’t hesitate to accept the job. The money is sufficient and puts food on the table for his wife, Daveena; his son, Nickolas; and stepson, David.

“He’s a hard worker,” his wife says.

He was born May 17, 1957, to Marjorie and Warren Hanson in Southeast Portland. His childhood involved frequent road trips and Sunday cartoons, his favorite of which was Huckleberry Hound.

Hanson remembers taking road trips with his family when they packed up the old, green AMC Ambassador and started driving. “We’d just go,” he says.

With just an intended destination and a road map, the Hansons often took to the road for weeks. Around 5 p.m., they would start looking for a motel, and the next morning, they were back on the road, oftentimes heading to a relative’s home in Montana.

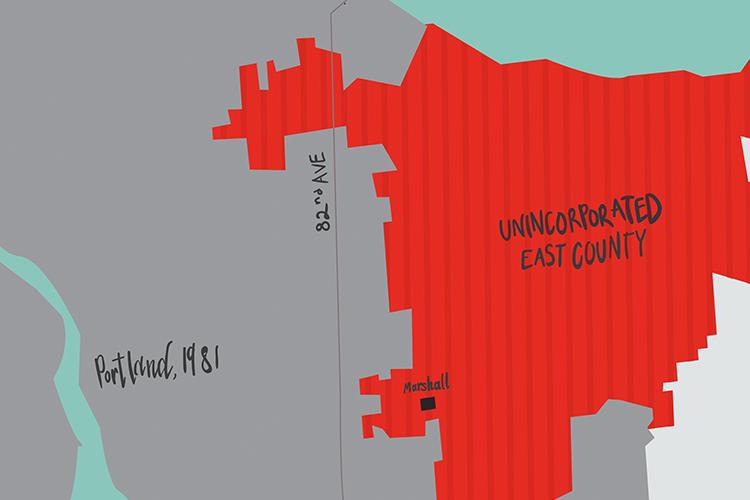

When Hanson reached Marshall High School, he had lost motivation to go to class and his grades quickly declined. “If I didn’t like the class, I didn’t go,” Hanson says.

When his sophomore year rolled around, Hanson knew he wasn’t going to graduate because he hadn’t earned enough credits. He recalls what he describes as one of the worst days of his life in 1975, when he was working as a short order cook and a group of his friends, who had just returned from their high school graduation, came in “cap and gowns, waving diplomas.”

“Unemployment with part time jobs just doesn’t cut it.” – Brian Hanson

After two years of working a variety of short-term jobs including stints at a seafood restaurant and Fred Meyer, Hanson realized he wouldn’t be able to get hired without a high school diploma.

In 1977, he enrolled at PCC in order to earn his diploma but it wasn’t until 1979, nearly eight years after beginning high school, that he finally was able to graduate. After receiving his diploma, Hanson registered at Portland and Mount Hood community colleges, where he was just a handful of credits away from earning an associates degree in general studies.

By 1981, Hanson, 24, enlisted in the military and was sent to Korea twice. “It’s a lifestyle, not a job,” he says of his service. When he returned from overseas in 1989, Hanson was stationed at Fort Carson in Colorado Springs, rebuilding large components in trucks and tanks.

In March 1991, while Hanson was driving to Fort Carson to pick up a fellow soldier and go to church, something caught his eye. A United Airlines Boeing 737 was attempting to land at the Colorado Springs airport when a malfunction in the rudder power control unit caused it to drop from the sky. Hanson watched as the plane turned belly-up and headed downward. He saw a billow of smoke rise in the sky.

Hanson rushed to the gas station and told another man what happened. As it turns out, the man he was talking to was an air marshal and he called the accident in to the tower at the airport. The following days were filled with a constant stream of news vans and reporters covering the crash.

After the military, Hanson moved to Portland, where he bounced around to different jobs, the last of which was at Iron Mountain, a medical records storage facility. That was followed by three years of being unemployed. He married Daveena in 1999, gaining a stepson named David.

He had a series of short-term jobs, ranging from being a Wal-Mart employee to working a Dollar Tree in St. Johns to powder coating metals to stuffing advertising inserts into The Oregonian. “Unemployment with part time jobs just doesn’t cut it,” he says.

Daveena Hanson remembers it as a “stressful time for everyone.”

In the summer of 2011, Hanson went to Worksource in Southeast Portland and heard about a custodian job at Portland Public Schools. He applied and was hired part-time to work at Lent School before getting a full time position at the PPS administration building. “It was a fishbowl,” Hanson says.

He worked close to Superintendent Carole Smith and occasionally engaged in conversations with her. “She was a very personable lady,” he says. In the spring of last year, Hanson was transferred to Grant High School.

Today, Hanson’s days start at 5:30 a.m. He prays for a half hour before waking up his son, Nickolas, and driving him to Reynolds Middle School where he is an eighth grader. He then spends his next few hours before work napping or doing work around the house. At 12:30 p.m., he gives his wife a kiss and walks four blocks to his bus stop.

Hanson works the night shift starting at 1:45 p.m. He’s at school until they lock up after 10 p.m. Not being able to spend time with his family at night is his biggest complaint, but “I’ve got my weekends,” he says.

“This is what happens when you don’t pay attention.” – Brian Hanson

His day starts in the cafeteria, where he sweeps and mops the floor before emptying the trash. When school lets out at 3:05 p.m., he goes upstairs to start the bulk of his work. Usually, he’s assigned to classrooms in a quadrant of the school, but with the increasingly short janitorial staff, Hanson has to do more.

With a short staff, he says he only has time to “trash and dash” some days. That’s when cleaning consists simply of going into each classroom, emptying the trash and leaving.

Each day, his job also requires cleaning the bathrooms, sweeping the stairs and vacuuming the rugs near the door entrances. “It can wear you out,” he says.

He’s lost 50 pounds since he started working at Grant. His least favorite thing about his job is what he calls “deliberate messes.” He describes these as “things like graffiti, writing on desks,” or things of that nature. The worst culprits? Freshman classrooms.

His “lunch” hour comes about 6 p.m. Most nights, he doesn’t take time to eat. But on occasion, he’ll walk over to McDonald’s. His favorite thing to get is a Big Mac.

Charles Rinehart, a custodian at Grant, works closely with Hanson during the night shift. “He’s a good worker,” he says. “He pitches in to help and when I need him over at the gym, he comes over to the gym at 9 p.m. and pitches in.”

When asked what his favorite thing about his job is, Hanson says “the paycheck.” He enjoys the benefits he receives from his job and the daily interaction with Grant’s students.

On March 9, Hanson and his wife celebrated their anniversary. It’s been 15 years since their courthouse wedding. They say they are more comfortable with each other than ever. The two have developed the same taste for just about everything, except music.

After his son, Nickolas, graduates high school, Hanson would ideally like to go back to college and get his degree, or maybe go to a cooking school. He’s always been interested in cooking.

Looking back at his high school career, Hanson regrets the type of student he was. He hopes for a brighter future for his sons and for the students at Grant. He believes his story can help.

“I’d like to talk to some of these kids who aren’t doing well and say: ‘Hey, you know what? This is what happens when you don’t pay attention,’” he says.

He believes students are constantly shown how to be successful, but don’t see what happens if they aren’t. “I think some people, you know, probably need to hear the opposite side of it,” he says. “It’s very hard the older you get to get caught up.” ♦