On a frigid night in February 2009 audience members at the Keller Auditorium lean in eagerly as a young boy opens his mouth to sing. The stage lights illuminate his innocent, soft features. The world seems to hold its breath. All is silent, air sucked in and held, just listening – carefully – to the boy’s pure voice.

Onstage, Michael Kepler Meo sees nothing but a six-story wall of darkness. But he knows he’s got the audience at his fingertips, hanging on his every note. He can feel its presence. The stares fill him with adrenaline. With a final flick of the baton, the conductor leads Kepler Meo’s aria to a close, the last note melting away.

Since his first opera in 2009, Michael Kepler Meo has performed a total of six major operas and two world premieres, often as the only kid in the cast. His work has taken him all over the United States and as far as Europe.

Now a 15-year-old freshman at Grant and no longer singing the high notes, Kepler Meo is enjoying being just a student. As a preteen, his time was dominated by musical scores and stage lights. Today, you’re more likely to catch him in the Grant bowl playing ultimate Frisbee than hitting a high G at the end of an aria. And although he aches to be back on the stage, he is enjoying what high school has to offer. “If I was traveling, not only would I not be able to do something like ultimate Frisbee or track at Grant or just have a normal life,” he says, “I wouldn’t be learning the things I have to learn to get into college.”

Lisa Florentine, a local Portland voice coach who has worked with Kepler Meo, says when she met him the first time she knew she was in the presence of greatness. “He has all the qualities of musicality. And he has perseverance and discipline,” she says. But what stood out most to Florentine was his fearlessness.

“I can teach anybody how to sing better,” says Florentine. “But to be a successful performer, you have to have absolutely no self-doubt. You have to have absolute belief in yourself. And that’s what Michael has that makes him different than everybody. I don’t know how he developed it.”

Well, it seems he had it from the beginning.

• • •

Even as a baby, Michael Kepler Meo was always making weird noises with his mouth. His favorite toys were not the typical stuffed animals or scrunchy teething rings of a toddler.

He preferred a vacuum cleaner hose, perfect for blowing through. There was the noisy elephant trunk in the form of a rubber sealing gasket from the refrigerator door. Or the metal shell ideal for use as a makeshift horn.

These odds and ends commanded Kepler Meo’s attention. He spent hours meticulously developing a certain sound that he would repeat for the next week straight before moving on to create another one with some other important instrument.

“He was always very vocal, very mouth oriented,” says his mother, Trudy Luz, who didn’t think his behavior was out of the ordinary. (He was her first child and she didn’t have anything to compare him to, she recalls.)

At 3, Kepler Meo’s infatuation with swords, sticks and weapons began. “He was so macho as a little kid,” says Luz.

Obsessed with the Trojan War, Kepler Meo’s ultimate idol was Achilles, the Greek war hero. Luz remembers her son inhabiting his hero’s character. He’d prepare for battle using sticks and fake armor, signing “Achilles” on his towel cape and garbage can lid shield and demanding to be referred to by the name on a daily basis.

Seeking some balance, Luz signed him up for a free voice lesson she had come across while reading the magazine Metro Parent. “I put him into music and dance to explore that other side of him,” she says.

After a voice lesson, the coach said that while Kepler Meo had a good voice, 5 years old was a bit early to start private lessons. She suggested choir as an alternative. The first choir that Luz found was the Portland Boychoir, an all-male performing choir that trains boys 5 – 14 in advanced musical skills. Kepler Meo joined right away, alongside other kindergarten strangers with the same instructions. Instantly, it clicked. And he loved it.

At rehearsals, he always paid strict attention. Other boys his age would be squirrely and get distracted, fidgeting with their music and roughhousing with each other on the risers. But Kepler Meo didn’t take his eyes off the conductor for the entire hour of each rehearsal.

“I started to learn how to read music before I fully learned how to read words,” says Kepler Meo.

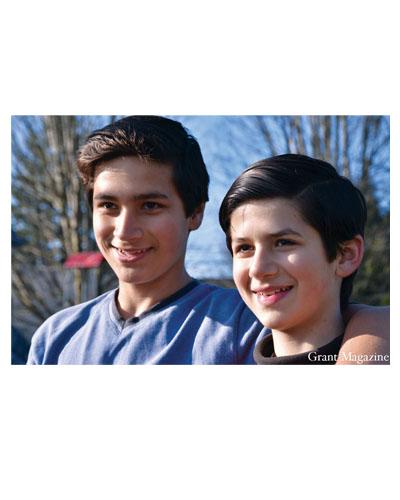

For four years, he honed his musical abilities, singing everything from pop songs to Vivaldi. Simultaneously, Kepler Meo and his younger brother, John, were performing as the only boys in a Mexican Folklore dance troop.

Practicing in unheated garages, one four-hour rehearsal was often all the time the group had to learn a routine before performing. Inside their broom-closet dressing rooms, Kepler Meo and his brother would layer on each of their several costumes before the show so that, with no extra time to change, they could peel clothes off in mid performance.

At age 9, Kepler Meo moved up to the performing level of Boychoir. His knack for singing was so apparent that artistic director David York recommended he audition for the Portland Opera in August 2008. “I knew they needed a boy who was capable of singing an independent part and had a clear powerful voice and Mike had those qualities,” says York. “They also needed someone who was confident and would be comfortable in front of a large audience.”

They were performing “Turn of the Screw,” one of the few operas with a sizable part for a young male treble.

In the world of opera, a principal role for a kid is somewhat rare. Composers are careful about writing child parts because smaller voices are often difficult to hear over the symphony in the pit. But the role of Miles, which essentially carries the plot, was a perfect fit for Kepler Meo.

Robert Ainsley, the chorus master for Portland Opera, was auditioning Kepler Meo. It was more than Kepler Meo’s pretty voice and good sense of pitch that sealed the deal. “It’s very important for a kid to have imagination if he’s going to actually portray a character on stage,” says Ainsley of casting children roles. “With Mike, so much was already in place in terms of his excellent sense of pitch. He has a wonderful sense of rhythm and counting, and a very natural sort of dramatically gifted theatre imagination.”

Originally, the show was double cast, with Kepler Meo, 9, sharing the role of Miles with a 13-year-old from Seattle. But a few weeks into training with Rob Ainsley, the other boy’s voice began transitioning from a treble to his adult voice – an event that ended up being pivotal in sparking Kepler Meo’s career.

The entire weight of the character of Miles then rested on Kepler Meo’s shoulders. Rather than weigh him down, it gave him a chance to bask in the spotlight. “Instead of having to share any attention with someone who probably would’ve outshone me actually in singing,” Kepler Meo says, “I was the phenom boy soprano that had come out of nowhere that was doing a really bang up job… I was able to be the Miles, instead of one of the Miles.”

The first day of group rehearsal was nevertheless daunting. Walking down the familiar long corridor to the rehearsal room, the same nerves that he felt for the audition bubbled inside of him. It was important to make a good impression.

Kepler Meo remembers it like it was yesterday. “The first rehearsal was like a performance for me – because the entire opera world hadn’t heard me perform then,” he recalls. As he turned the corner to the room, Kepler Meo continuously went over what Ainsley had told him in his head: “Every time it’s your time to sing, stand up.”

Luz was forced to take a back seat while her 9-year-old son navigated the unspoken pressure to do well. Thinking she could be there as moral support, Luz tried to walk into the rehearsal room with Kepler Meo but was denied access. The room was a protected space for the professional opera singers. Kepler Meo was on his own.

“Looking back in retrospect, at that point, you know, he was in,” Luz recalls. “But I don’t think it felt relaxed and comfortable like ‘Oh, I got this in the bag.’ He still felt like he was auditioning,” she says.

But Ainsley had prepared him well. And before he knew it, he was backstage on opening night, poised and ready for his debut entrance.

“It’s this kind of really harrowing experience,” he recalls, “of counting down the minutes – counting down the minutes constantly… warming up. But then, maybe two minutes before you go on stage, you kind of go into this moment of more relaxation. You’ve got a ton of adrenaline so you don’t feel nervous anymore. It feels kind of like a drop. You just feel super highly focused and super ready to do this.”

Once onstage, Kepler Meo never worried about the music. He just let it flow through him. By then, “it’s ingrained in you,” he says.

The rest of the opera went by in a flash. But Kepler Meo’s favorite part was yet to come: curtain call. “The second the music ends, you are like in bliss because you just completed something super duper hard and all that insane concentration evaporates and all you’re left with is complete exhaustion and bliss. And then you go out there and you see people clapping and you get to bow… and it’s so fun. There’s nothing like it!” he beams.

After completing all four performances of “Turn of the Screw,” Kepler Meo had an ‘Oh!-Well-that-was-fun!’ attitude, having no idea this was merely his start in the world of opera, or that his career as a professional singer had been ignited.

His performance quickly turned more than a few heads, and three months after the end of the run, Luz got an email from Houston Grand Opera asking Kepler Meo to audition for Miles in a revised version of “Turn of the Screw.”

Seven months later it was off to Houston.

Being homeschooled made traveling no problem. Kepler Meo and his mother packed the essentials and hopped on a plane to Texas. There, they got a small apartment: their home base out of which they would live and breathe opera for the next six weeks. On his days off, Kepler Meo was free to explore a new area – his favorite part about traveling for work. His days were filled with a visit to the aquarium or a night out on the town with mom. “It’s like a free vacation that you’re getting paid for,” he says.

• • •

After performing in Houston, things took off. Kepler Meo was next contacted by Paul Kilmer, the artistic administrator at the Opera Theatre of St. Louis.

Kilmer had been in search of a young treble to play the lead part of Charlie in Peter Ash’s new world premiere of “The Golden Ticket,” an operatic rendition of Roald Dahl’s “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.”

Kepler Meo soon received the score in the mail – an inch thick, golden, hardbound book suffused with pages upon pages of music. Once again using Ainsley’s help, Kepler Meo began ingraining the music into his mind. He memorized his arias, flushed out the difficult clusters and picked apart the story itself.

Who was his character? What was his relationship to the other characters? By the time he got to St. Louis, he had to know the whole opera front, back and sideways – so that he’d be ready to start blocking the show right away.

Upon Kepler Meo’s arrival, Kilmer immediately knew that he was not just some 11-year-old kid that adults would have to cater to. “He became like everybody’s little brother,” recalls Kilmer. “His levels of self-confidence and maturity were quite incredible… He just came in and did his job and sang beautifully.”

By the beginning of the two weeks of dress rehearsals, the cast was a small family. Brother John, with Kepler Meo and Luz for the first time, earned his spot in the family by attending every rehearsal and becoming a supernumerary to his brother. Soon, he too had memorized the entire opera.

The boys developed a game to help with score memorization. “I would say a word – one word – and he’d try to guess the phrase afterwards,” John recalls. “And in ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ there are a lot of unique words, because it’s Roald Dahl… And he sometimes would come up with an answer that I wouldn’t think of. ‘OK, I’m thinking of four answers. Try to get all four.’ And so we’d go through the whole lyrics. It was really cool.”

After the last of the six performances wrapped in June 2010, Kepler Meo, John and their mom returned to Portland. Until four months later.

As a way to make the business more economical – it costs roughly half a million dollars to produce an opera – the Opera Theatre of St. Louis was co-producers of “The Golden Ticket” with Wexford Festival Opera in Ireland. Kepler Meo was again invited in October 2010 to portray Charlie, this time in the small fishing town of Wexford.

“It was a different way of life there,” Kepler Meo recalls. “You could walk around and there were medieval walls.”

They moved into a duplex with a big backyard, a trampoline and baby rabbits. Life in Ireland was glorious. And all too fleeting. Sad to kiss their almost-mastered Irish accents goodbye, the boys and their mother hopped back on the 14-hour flight home to Portland six weeks later.

And the process repeated again. And again. After Ireland, he performed in Los Angeles in February 2011. Then New York in March. Then St. Louis again in June. He was in such high demand that he rarely got more than three months at home.

“He used to say that he had the life of a double agent,” says Luz, “because he’d go and be with all these old, rich opera people and everybody knew him and admired him, and he’d come back and nobody knew anything about that and it was completely a normal life.” But Kepler Meo wasn’t complaining.

“He cut his teeth on being in front of people,” says Luz of her son’s obvious adoration of the fame.

When a CNN camera crew followed his every move like paparazzi backstage at an LA performance, Kepler Meo told his mom: “I could get used to this.”

In 2012, Kepler Meo took his first stab at performing something other than opera: musical theatre. “That was a big difference from opera. You get at least two days of rest in between every show,” he says. “In musical theater, you’d be lucky if you don’t get three shows a day.”

As the only kid not double cast, he performed about 50 shows of “El Zorrito” in May and then 60 more of “Peter Pan” in December.

This was the last show Kepler Meo was able to sing as a treble – after that his voice broke, no longer able to reach an octave lower than the highest note on the keyboard.

Last year in February, Kepler Meo completed his final opera before entering high school: Nolan Gasser’s world premiere of “The Secret Garden” in San Francisco. He sang as a child tenor, a rare and unusual part for a boy of 14.

Now that Kepler Meo is mixed in the larger pool of male tenors, it will be more difficult for him to land roles because there are more people vying for the same part.

“If I want to do opera again, it’s going to be as one of the adult[s] that I was working with and they’ve been doing it for years, through college,” he says. “I’d basically have to start over at this point.”

• • •

The morning bell at Grant rings and Michael Kepler Meo ascends the short, puddled steps of the school’s main entrance. Dressed comfortably in a worn gray t-shirt, jeans and a pair of enormous green, white and black basketball shoes, he heads to class with a soft smile.

His mind wanders to the upcoming afternoon that is free of vocal warm ups or breathing technique. Maybe some Rome Two Total War then out to the park for some ultimate when he gets home, he thinks to himself.

Kepler Meo enters the choir room. It’s second period: A Capella, Grant’s auditioned choir of 76 in which Kepler Meo is currently the only freshman.

John Eisemann, Grant’s choral director, clearly recalls Kepler Meo’s audition last spring. Not knowing what to expect after watching the impressive videos online of Kepler Meo in past operas, Eisemann was somewhat leery to be auditioning a freshman.

“From what you see online, you would expect some totally self-confident, diva child,” says Eisemann. “And in walks just the sweetest, most innocent, unassuming boy with sport shorts on, a faded gray, blank t-shirt with some tears in it and some scuffed track shoes.”

After singing as a solo artist for five years, Kepler Meo is more than up for the challenge of re-learning how to be an ensemble singer. Eisemann agrees that while learning how to blend his voice with others is a challenge for Kepler Meo, it’s nothing he can’t overcome.

“What’s remarkable about Michael is that he’s not discouraged by it at all,” Eisemann says. “When I go ‘Michael, Michael. Less.’ He doesn’t shy away like, ‘Oh, I’m hurt now.’ He’s like ‘Oh, OK, I get it.’ That’s his professional training kicking in, in an ensemble setting. His professionalism is just outstanding.”

From a distance, you’d never know that Kepler Meo has spent the better part of his life singing arias. And although his career is on pause for high school, he isn’t ready to give up the life of an opera star.

“I’m enjoying being able to go to high school. But I’d still rather be traveling and doing opera. If I could go back… now, I would. It’s an obvious choice for me as a career. Something that I sing in,” he says. ♦