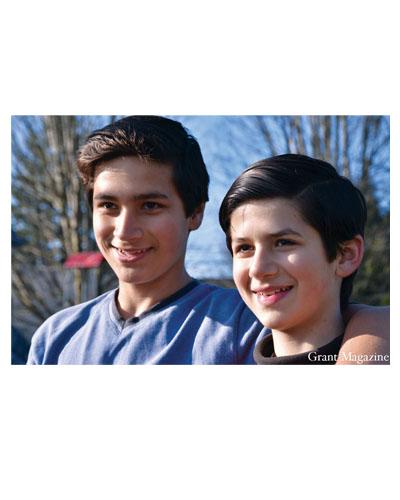

Fifteen-year-old Dominic Flesey-Assad gets off the short yellow school bus just as the sun begins to cast its light on the face of Grant High School. Backpack in tow, he cuts a diagonal path across the lawn.

Heavy metal doors swing shut as he enters the crowded hub of Center Hall. And just like that, he’s in his element again.

In one hallway, he sees three people who call out, “Hi, Dom.” Usually, he gets to them first. He passes a group of students clustered around a locker wishing a girl happy birthday. Flesey-Assad gives the girl an excited set of high fives and moves on.

Says Grant senior Ingra Buys, who met him through a club at school: “He just always seems to care about how people’s days are going and always tries to talk to people.”

If Flesey-Assad had a title, it’d be Grant’s official greeter. He confidently strides down Grant’s hall each day, dishing out welcomes here and there. And for several hours each day, he stops at a classroom on the north side of the school – home of the Life Skills program. There are three Life Skills classes at Grant available to kids with differing disabilities.

Within Flesey-Assad’s class, a spectrum of capabilities exists. In the far corner of his basic math class, one kid must be reminded several times to not chew an eraser. Others have difficulty finishing a worksheet. What the classroom gives these kids, and their parents, is extra supervision.

Flesey-Assad has a traumatic brain disorder, the result of a car accident his mother was in when she was pregnant with him. Growing up, he knew he was different. His disability always bubbled to the surface in some way. A slur in his speech. A slight tremor in the hands. Tight muscles.

But have a conversation with the eager, bright-eyed sophomore and you’ll forget he just learned how to tie his shoes this year.

In the Life Skills program, students focus on learning the things they need to live somewhat independently. Teachers in the program push kids to their limits, something that many years ago wouldn’t have been possible. Before, most kids with cognitive disabilities didn’t go to school, and once they did, they were often cordoned off in a separate classroom.

Now, a student like Flesey-Assad blends into the school population much more easily. And he’s done it with unusual ease.

As his mom, Seanna Flesey-Sorensen, puts it: “People meet Dominic and they’ll catch his speech is a little different than ours or his style of talking, and say, ‘What’s with Dominic?’ or ‘What happened?’ He’s just Dominic. We’ve always treated him like that. We don’t treat him with kid gloves.”

Not many know about the hurdles Flesey-Assad has faced. The first one came before he was even born.

When Seanna Flesey-Sorensen thinks back to the day, she only remembers bits and pieces. Like the fact that she was wearing a black- and white-striped shirt that she would never get back. The doctors cut it off after the accident.

She was 36 weeks pregnant when she climbed into the car with then-husband Greg Assad and their 4-year-old daughter, Jazmyne, to go to a barbecue at her dad’s on the afternoon of May 6, 1998.

Jazmyne sat in the back seat, plopped on her booster seat in the middle, a glass container of barbecued chicken resting on the seat next to her.

One moment the family of three rolled smoothly down North Lombard Street in the right lane. The next, a driver changed lanes without checking the blind spot, ramming into their Datsun. They went careening into a telephone pole.

Everything fell apart at once.

Barbecue sauce coated the back seat as the glass container shattered. Jazmyne flipped out of her booster seat.

Greg Assad remembers the impact felt like getting hit with a baseball bat in the back. His chest was bruised, and he had scrapes on his hands and knees as he reached into the back seat to grab Jazmyne. She had a large knot forming on her head. He rushed to open Flesey-Sorensen’s door and get her out. It wouldn’t budge. The window was shattered, glass was everywhere and the door was stuck shut.

Gripping his daughter in one arm, a strength suddenly possessed Assad as he tried to pry the door open on the passenger side. “I felt like Superman and I had to get that door open. I was bending the L-frame on the door because the door wouldn’t open,” he recalls.

Flesey-Sorensen wasn’t seriously injured, mostly just dazed, but concern for her unborn son was overwhelming.

A crowd of nervous onlookers gathered and within a few minutes an ambulance arrived to take Flesey-Sorensen away to Legacy Emanuel Hospital. The paramedic who picked her up later wrote in a book made by Flesey-Assad’s grandfather about that day: “I was more frightened for you than for any patient I’ve ever had in 10 years of working in an ambulance. I will always remember you.”

At Emanuel, doctors discovered the unborn baby had an extremely low heart rate. Flesey-Sorensen had to have an emergency Cesarean section. Miraculously, at 5:36 p.m., Dominic Flesey-Assad was born. It took an army of doctors and nurses 20 minutes to resuscitate him.

Flesey-Sorensen wasn’t able to see her son until four days after his birth. Doctors told her there was a 50-50 chance he would make it. Soon after, she recalls being taken into a small room where she was told her son might face life in a wheelchair.

The future was shaping up to be very grim. Her son had survived, but the situation was becoming more complicated. She already had Jazmyne, and as a young mom, she wasn’t sure “how I could balance both of them and take care of both of them. And nobody wants to hear that about their child. So it was scary. Very scary.”

A young Dominic spent about a month in the Intensive Care Unit at Emanuel and was diagnosed with a form of traumatic brain injury. Doctors hypothesized that his condition came from a lack of oxygen caused by a stroke. A low response test at the hospital early on catered to the parent’s worst nightmares.

“I just remember them saying that he…wasn’t going to be able to walk, talk, do nothing,” his dad says today.

Remembers Flesey-Sorensen: “It was life-changing.”

During his tenure at the hospital, Flesey-Assad certainly made an impression on the doctors and nurses. One nurse wrote: “I have threatened your dad that if he doesn’t bring you back to see us we will come after you!” Another said they “dub thee, ‘The Dominator,’” fittingly for his already-persevering attitude.

Once Flesey-Assad was brought home, professionals of all sorts came to visit and help in his recovery. There were physical therapists and educational coaches. They gave him exercises to improve his range of motion. By his toddler years, he started to see a neurologist.

For the most part, doctors could only hazard a guess about the boy’s future. It was like shooting in the dark with so little known about the brain.

At age two, his dad got Flesey-Assad involved in swimming. Because the pool couldn’t offer one-on-one lessons, Assad took it into his own hands to teach his son the basics. The swimming would become a large part of his childhood. Not only did it help improve his “range of motion,” according to his dad, but it was also an activity he enjoyed participating in with his sister, Jazmyne.

Even today, the two will spend hours at their grandparent’s pool in the summertime, though Flesey-Assad has ditched the water rings he had to use early on to stay afloat.

He also started bowling as a 4-year-old, something he still does today through a local bowling league and the Special Olympics.

Flesey-Assad was always daring. One day on Mt. Hood, he had a close encounter with a mini-snowmobile. Pulling back on the throttle, a young Flesey-Assad soared off at high speeds, knocking a plastic barrier down and coming close to running over his mother. But afterward, he got on for a second try.

Flesey-Assad entered elementary school at Richmond. Although he lived in the Ockley-Green neighborhood, his sister had gotten in five years earlier through the lottery, which gave him preference.

His short time at Richmond – he would be displaced to Glencoe in just a year – was anything but smooth.

After all, in the time that Flesey-Assad was making the transition into elementary school, Richmond itself was changing. That year, 2004, was one of the first years PPS mainstreamed students with developmental disabilities. Before, these students had been put in separate classrooms with different instructors.

While some teachers were outwardly frustrated at the new work they had to put in with these higher-need students, others were simply inexperienced in the practice of working with kids with disabilities. And schools all over the country like Richmond had been undergoing a transformation with the goal to help students with special needs.

In 1967, 200,000 people with disabilities were held in mental institutions, according to the U.S. Office of Special Education Programs. In 1970, only one in five children with disabilities received a formal education.

Five years later, the passing of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act set the course for developmentally disabled students. In 1990, another act took a key step toward putting an end to the alienation of kids with disabilities in school. The act required all kids with disabilities to have access to an education and gave families the ability to argue against changes made to it.

But those who were caught in a school’s transition period, like Flesey-Assad, could sometimes have a rocky experience.

One day in second grade at Glencoe, Dominic was called up to the front of the class and instructed by the teacher to “tell everybody why you talk different.”

He was bullied by a kid who belittled and embarrassed him, his mom says. Flesey-Assad remembers the kid calling him names. When he asked the teacher for help, the bully said Flesey-Assad was lying.

But when things didn’t go well at school, Flesey-Assad always had the support of his family. His parents had divorced when he was two and Flesey-Sorensen remarried. But the former couple remained close for the kids. Flesey-Assad split time between his dad, his grandparents and his mom. He also talks to his mom’s uncle every day on the phone and the two have a close relationship.

Jazmyne Flesey-Assad, who is moving to her dad’s to help keep him company, attends Portland Community College. One of her most important lessons for her brother? Worry less about others and think for himself.

Assad rattles off the things she has helped her brother with. Color coding his clothes. Planning out his outfits. Doing the laundry. All things that will help him become more independent.

They have long-standing traditions. Every year on Christmas Eve, he camps out in her room to watch The Christmas Story marathon. Then, early on in the morning, the pair runs downstairs to open stockings, check that presents have arrived, and then slip upstairs and back to bed. On Valentine’s Day, they go out to a movie and dinner.

By the time Flesey-Assad finished his four years at Glencoe, he and his family were ready to find the right fit for what came next. They took the time to visit different schools and see how the kids were treated.

It didn’t go unnoticed at the district level.

At the start of their education, kids with special needs are assigned one person in the school district to oversee their case and essentially manage their education. That person then decides, based on the student’s history and their functionality, which classroom they should be placed into within the school system.

And the representative Flesey-Assad had was none-too-pleased at the family self-selecting a school, something that was very “frowned upon,” according to Flesey-Sorensen. “She said, ‘You are not allowed. This isn’t like real estate, like visiting properties or shopping for a home.’”

Despite this, the parents forged ahead. What mattered to them was that their son be put in a place where “it was a good community of people. I guess just the overall feeling of the classroom was important,” says his mom.

They didn’t have to wait too long before finding the school that meshed with his circumstance. When they called Chrysann Lowe at Beverly Cleary-Fernwood, they were instantly struck by her friendliness. Many of the schools they had contacted required the family to go through the district representative before paying a visit to the school. But Lowe “welcomed us in the classroom, no questions, no struggle, no anything,” remembers Flesey-Sorensen.

Lowe had met Flesey-Assad at Glencoe where she worked for a month before getting transferred. She was pleased to see he would be in her class as a sixth grader. She explained to Flesey-Assad and his parents about the different opportunities students were given in her class. They took field trips out into the community to practice public transportation skills. They also planned meals, learned how to budget money, and then cooked the meals right in the classroom, which allowed them immediate feedback for their work.

At Beverly Cleary, Flesey-Assad “blossomed.” The infectious personality that had touched many people expanded even more in a place where he felt “emotionally supported.”

Lowe remembers his drive and hard work. “He is a person who knows what he wants, and is willing to work hard to get it,” she says. “And so that’s a quality we don’t see in all kids, and certainly not a quality we see with kids who have to work as hard as Dominic to make progress.”

At one point, Flesey-Assad was interested in taking outside science classes. Lowe gave him a clear set of guidelines that he would have to meet to be able to take them. “He just really methodically worked right down that list of things that he needed to have accomplished” to get to the class, she remembers.

When Flesey-Assad graduated from Beverly Cleary in 2012, his parents planned for him to attend Grant. This choice, once again, didn’t go without resistance from the Special Education program.

His dad recalls going through five or six people in the school system, advocating for his son to continue on to Grant with his other Beverly Cleary classmates. The alternative was for him to be shipped over to Roosevelt. The parents worried that he’d disappear into a mass of students he didn’t know.

For the most part, Grant was the practical place to put Flesey-Assad: his grandparents could pick him up after school and he could continue on the same trajectory with familiar people.

“Unfortunately, families who have special needs children aren’t aware a lot of what their rights are, and you have to really advocate for your children,” Flesey-Sorensen says. “If they’re mainstream or in a special classroom, it’s no different. You just want your kid to go to a school where they’re going to be successful.”

Flesey-Assad and his parents won. He would be attending Grant. Says Flesey-Sorensen: “He’s embraced the Grant community and it’s really embraced him back.”

Margarett Peoples, a teacher for one of the school’s Life Skills classes, didn’t notice anything special about the incoming freshman, at least not at first.

But, over time, she realized how positive a person he is. As a Life Skills student, some of his classes were not with other mainstream kids. In turn, Flesey-Assad had fewer opportunities to go out and meet people than most. It didn’t stop him from regularly making lunch plans with other kids.

Jennifer Elder, whose son Morgan is in the program, points out: “A lot of the kids in the class, like Morgan, are not very social. They sort of stick to themselves, they have their own interests, and that’s sort of what sets Dominic apart,” she says.

He offers a connection between the student body and the disabled population, Elder says.

“He’s an ambassador for the classroom, because if other kids know just one kid in Life Skills, it’s going to be Dominic, and he’s a pretty great personality,” she says. “I really appreciate him being the face of Life Skills.”

There’s no doubt he loves school. Last December, the only time his mom could find for the family to get a Christmas tree was in the middle of the school day. She quietly mentioned to Flesey-Assad, always a holiday lover, that he could take the day off from school. He decided to go to school instead.

On a recent day in January, his dad pulled out a green slip of paper. It was a report card for the quarter – all As.

Today, all neighborhood high schools in PPS have special education programs. Vice Principal Kristyn Westphal says mainstreaming kids with disabilities has changed the school population and how many students think.

Teachers have also adopted an attitude of trying to put as few restrictions on a disabled student’s education as possible. Many are able to take outside electives, or even subject classes – like student store, choir and history.

Says Elder, whose son takes ceramics, of the system, “It kind of keeps the society of the high school together.”

t around 6 p.m. on a Friday night in mid-January, a warm Pizza Schmizza near Lloyd Center is abuzz. But not because the restaurant is busy. In fact, most of the motion in the near-empty restaurant comes only from the televisions mounted to the walls and a table in the far corner.

There, a family sits. It’s a little more complicated than a family. Two siblings. Two divorcees. Two proud grandparents. A cousin. It’s not your typical family dinner but it works.

A waitress comes by to ask if there’s a birthday, assuming this from the opened gift bags on the floor and two cakes that have been brought out. It’s Nana’s, they tell her. The waitress asks whose Nana she is. Assad fittingly explains about his mother: “She’s Nana to everybody else. She could be your Nana, too.”

Just as she leans in to blow out the cake, there’s a sudden outcry at the table – nobody’s sung Happy Birthday yet.

The group launches into a slightly discombobulated version of the song, with Flesey-Assad singing loud for the woman whom he’s played many competitive Uno games against.

At the end of the song, Flesey-Assad gives a giant puff to the already-smoking stumps of candles, drawing laughter.

He does that a lot – lighten the mood. Earlier that day, he’d helped calm down a kid in his Life Skills class who was concerned about another student cheating off his paper. Wisely and gently, he told the flustered kid: “So, just ignore it.”

From the initial diagnosis of the doctors to now, it’s clear Flesey-Assad has exceeded expectations. “That’s why it’s so hard for me to say what’s going to become of Dominic’s future,” his mother says. “It’s just really hard to predict his future because anything is possible.”

Right now, Flesey-Assad has his own goals. One day, he hopes to get a driver’s license. In the spring, he’s slated to be an assistant on the baseball team. But he might want to start playing the sport eventually.

Chalk it up to family support, Flesey-Assad’s own fighting spirit, or just pure luck, but Flesey-Assad has defied the odds. His parents point out that it’s like little guardian angels have surrounded Flesey-Assad since the day he was born.

His mother recounts the story of how she went to see a psychic with a friend after her son was born. Without Flesey-Sorensen saying anything, the psychic gave an accurate portrayal of what had happened during Flesey-Assad’s birth. She told his mom that her baby had gotten a bump on his head, and that her grandmother – who had since passed away – had held the boy in her arms, just like those guardian angels.

In an odd way, it all seemed to make sense that a family member was looking out for Flesey-Assad on the very day when his life hung in the balance.

As his mom puts it, family has “been his foundation.” ♦