Eddie Tellez and his sister, Maria, walked into the men’s bathroom to check on their mom. The stall door was flung open and their mother was sprawled out, lying limp and motionless against the toilet. Nine-year-old Eddie Tellez didn’t know what was happening. He thought his mom was dead. He started to breathe fast and his heart raced. He ran outside, panicked.

She had overdosed on heroin, coming close to death. The Tellez siblings became foster children after their mother was deemed an unfit parent. They’ve been homeless. They spent time in four different foster homes. And they say they’ve endured a variety of abuses and psychological trauma that will haunt them the rest of their lives.

Oregon’s foster care system is massive and sometimes children fall through the cracks. Statistically speaking, a tremendous number of people who spend their childhood in foster care end up homeless, in abusive situations or become poor. Only a small number go to college. But Eddie and Maria Tellez are anomalies.

Today, the Tellez siblings have survived, in part, because they were adopted by a supportive family. They managed to separate themselves from their horrific past and are working at becoming successful young adults despite their checkered childhood.

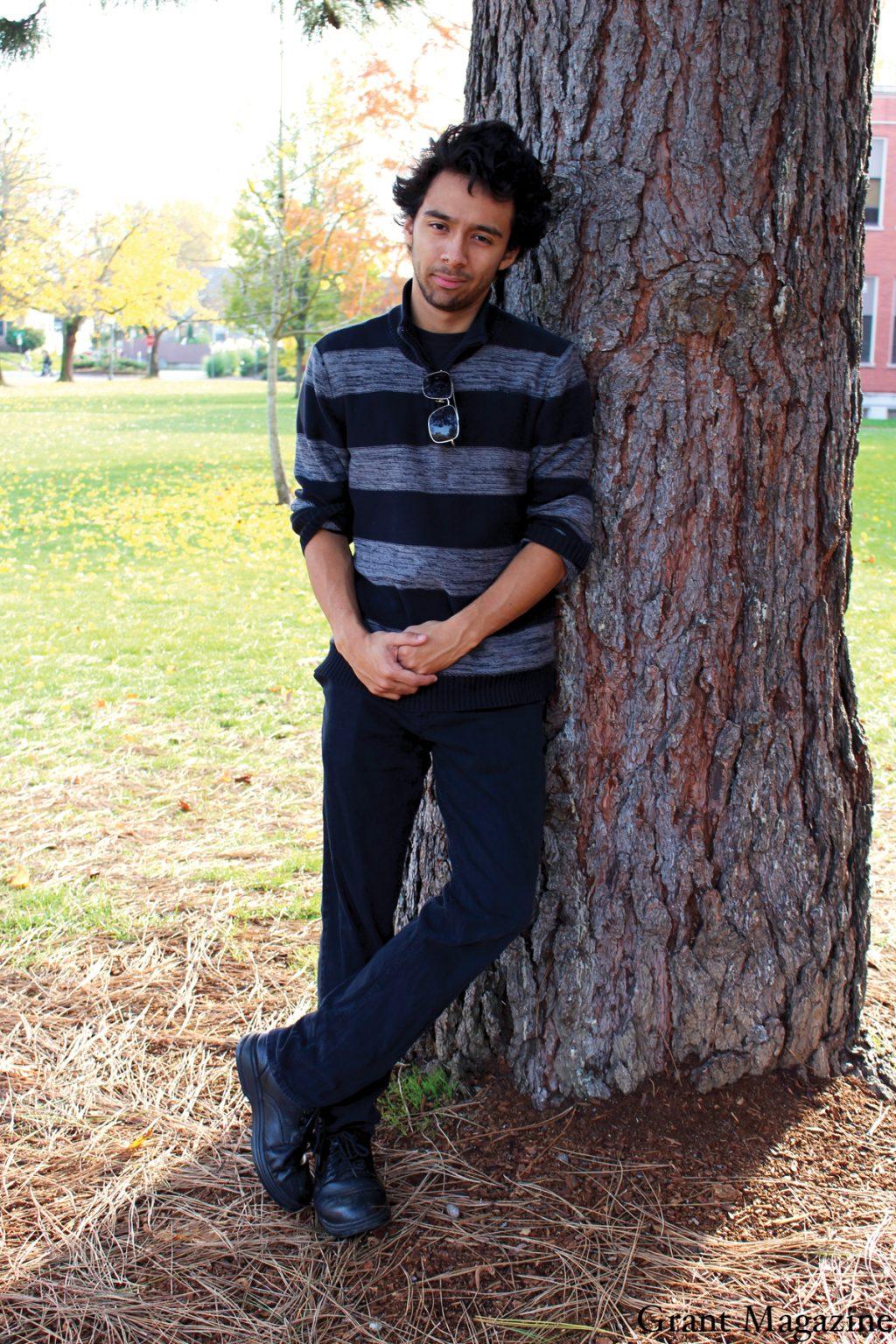

Eddie, 16, is a newly elected member of Grant High School’s student government, representing one of the four positions held by the junior class. Maria, 14, is a freshman who aspires to be an artist and a teacher.

Growing up, Eddie and Maria Tellez didn’t have much money or parental guidance. Their father left when Eddie was two and they lived in a small apartment in Southeast Portland with their mom and grandmother. Their mom began a transition into manhood in high school, taking hormones and changing her name to a man’s name. He identifies as male, but the kids still call him Mom.

The children didn’t have rules and ate a lot of junk food. Their mom had a drug habit and their grandma did drugs, too. They kept it hidden mostly, but the children were exposed to drug users who regularly came to the apartment.

Their grandmother died before Eddie made it through second grade. After that, their mom didn’t have enough money to keep the apartment, so he decided to go to Miami to stay with family. The three scraped together enough money to buy enough groceries to last the trip. Then they climbed onto a Greyhound bus and made their way across the country in three days.

“Our room was like a jail cell.” Maria Tellez

Eddie Tellez recalls crossing the Rocky Mountains, traveling through Wyoming and Colorado, and then down into the southern states. “I wondered how all of this could be one country,” he says of the trip.

When they arrived, plans with family fell through and they were forced to move into a homeless shelter in Miami. Eddie remembers starting third grade. A lot of the kids in his class were loud and disrespectful. He felt like he was the only one who cared about learning.

He remembers there was sometimes gang violence near the school, and once the school was locked down because of a report of a dead body.

After a few months, they gave up and rode a bus back to Portland. They bounced from one homeless shelter to the next. Eddie remembers that everything in the shelters was dirty, especially the mattresses the children slept on. The shelters were “not an ideal location to live, especially for a child,” he recalls.

Four homeless shelters later, they found a place to stay called the Good Neighbor Center, a social service agency that helps families get back on their feet. It was clean and hospitable, with separate living units connected by a courtyard. It was here that the Tellez siblings’ lives would take a sharp turn.

Eddie Tellez was playing Yu-Gi-Oh cards in the courtyard on the day he found his mother in the bathroom. After the drug overdose, the Department of Human Services took the siblings to an emergency home for a night. Then they were shipped off to Hillsboro to live with a foster family.

The two children, then nine and seven, didn’t fully understand the circumstances of their situation, but they didn’t like their hosts, who were strict. Eddie remembers telling the caseworkers at Human Services that the family didn’t feed him so he could leave.

Next, the children were placed with a couple in the same town that had two kids. Everyone got along well and it seemed like a good fit for Eddie and Maria. But it wouldn’t last.

Eddie remembers that his sister was “like a bomb about to explode.” She would often burst out with temper tantrums, crying and screaming. It became too stressful for the foster family and Eddie remembers that they had to leave before he finished fourth grade.

The next stop was worse than anything they could have anticipated.

At first, they were excited when they met the new foster parents, a young couple. They had other foster children staying with them at the time. They also had the husband’s dad helping to raise the foster kids. The problem was, Eddie Tellez recalls, that the dad was a convicted child molester.

All of the kids were treated like dogs. “Our room was like a jail cell,” Maria Tellez recalls. The only time the kids were allowed to leave their rooms was for meals, which they were forced to eat quickly before being sent back. If they were seen crying or showing any emotions, they would be ridiculed, sent to their rooms and forgotten.

“You just feel isolated. From like, everyone. That’s one of the things I’m still dealing with, because my brain has been wired to be like that.” -Eddie Tellez

When another child at the house told Eddie Tellez that the host’s dad molested him, Tellez didn’t know what to do. He kept it to himself.

That boy wasn’t the only mistreated child. When one of the girls staying there broke the rules, she was taken into the bathroom, the Tellez siblings remember, where she would scream for hours.

School was one of their only escapes. Eddie Tellez loved school and was always a good student. The psychiatrists noticed his high scores on cognitive tests, indicating a high IQ. They suggested he enter more academically rigorous programs, like Talented and Gifted, but his foster family life never allowed him to get tested for the advanced programs.

Instead, Eddie Tellez challenged himself. He immersed himself in his schoolwork. But when the day ended, he knew he had to go back home where the problems would haunt him again.

When caseworkers from the DHS came to check on the family, the foster parents put on a show, Eddie Tellez recalls. They acted exceedingly courteous and if any of the kids brought up complaints, the couple would promise to make immediate improvements.

Once during the winter, the adults caught Eddie sneaking food. He didn’t get any Christmas presents that year, sitting in silence as he watched everyone else open gifts.

The only thing the Tellez siblings could rely on were the weekly visits from their mom that kept the kids going. But after a year with the foster family, Human Services officials took the Tellez children away, placing them with a family in Beaverton.

They moved in with a very kind, very religious Filipino family in the suburbs in Beaverton. The new lifestyle helped each of the children change for the better. Eddie felt more comfortable at his new school. Maria’s tantrums fell off.

At the same time, they were told the odds were slim that they’d be placed back in the custody of their mom. Eddie Tellez accepted it immediately. “I sort of outgrew my fantasy that I was going to stay with my mom,” he says.

However, Maria Tellez recalls that she felt at some point they might all be together again. When she learned this was no longer possible, she was devastated.

In 2010, the Tellezes stayed with Kate Runyan and her husband, Steve Mitchell, for a weekend to test the waters. And they’ve been with them ever since. “I just wanted a stable household more than anything,” Eddie Tellez says.

When Runyan married, she initially didn’t want kids. However, she and her husband decided adopting foster children seemed like the right choice for them. Their first adoption was in Oakland, where the service workers quickly paired them with Temiko, or Miko, who was five years old at the time. Because of Miko’s youth and vivacious personality, the couple shared an immediate connection with him.

A few years after his adoption, Miko was lonely, and he announced he wanted an older brother.

Four years after Miko’s adoption, Eddie and Maria Tellez joined the family. Today, they live in the Northeast Portland neighborhood of Laurelhurst. When asked about their first impression of the two, Mitchell says: “They were both really bright, smart kids. They had a great smile, and…”

“Nice hair,” Runyan interjects. Mitchell laughs. “Nice hair,” he agrees. But it was evident that the two had gone through a lot.

Their experiences with foster care had left them guarded and standoffish. Eddie Tellez had become very “parentized,” as he recalls, taking it upon himself to make decisions for himself and his sister.

Trust was a huge issue for both of the siblings. Maria Tellez tested their new parents with outbursts and bad behavior, a common thing for foster children to do. She would sit on the ledge of her second floor window and threaten to jump. She also threw herself down the steep, wooden stairs in the house. Eddie remained extremely detached from his new parents and kept to himself most of the time.

Runyan and Mitchell were overwhelmed, they recall. They worked hard to build strong relationships with the new additions to their household. Runyan was so stressed out that she lost 30 pounds in their first year together. They couldn’t believe they had taken on such a difficult task. “You think you’re giving when you adopt, but you are really giving when you just continue to stick with it,” Runyan says. “Man, you have to be really strong.”

“I do my best in the present to make life better in the future.” – Maria Tellez

Despite the difficulties, Runyan and Mitchell persevered. For once, the Tellezes found themselves with parents willing to work through the issues, and the parents slowly gained their trust.

Today, the Tellezes have been with their adoptive family for four years and have grown close to their little brother, Miko. Maria Tellez especially shares a strong relationship with him. She wishes that she and her adoptive brother were twins rather than a year apart, and she misses spending time with him at school. Next year, Miko will join the Tellezes at Grant.

Now in high school, the Tellez siblings have come a long way from the homeless shelters and abusive foster homes of their not so distant past.

Maria Tellez is more social since the start of the school year. She enjoys writing and Japanese comic-style art, and she’s taking first-year Japanese. Being at Grant has allowed her to embrace her creative side. “I guess I’m just more open with myself and talking to people,” she says. “It really feels like you’re free there. Now I just have to focus on the things I didn’t really get as a child.”

She wants to move to Japan in the future and immerse herself in the culture she finds so fascinating. She wants to become an English teacher and hopefully a part-time artist. “I’m just gonna live such a good life. It doesn’t matter if I’ve lived a horrible life, it matters what’s gonna happen,” she says. “So I do my best in the present to make life better in the future.”

Eddie Tellez makes his mark in the classroom. Whether it’s A.P. European history, spewing facts about ancient Greek and Roman scholars or citing Freud and Nietzsche, he feels at peace. He especially loves Nietzsche’s idea that you need to suffer in order to become great, due to his own ordeals in the foster care system. He reflects on his circumstances often. “You question yourself so much that you find your, like, foundation that can’t be questioned,” Eddie Tellez says. “Sort of like the core of your being, basically.”

Earlier this month, he won election to one of the four posts for Junior Representative in Grant’s student government. “More than anything, it was an experiment to see if people see me as a leader, and if I could earn their trust,” he says.

He wants to create a student union and help make improvements at the school. Winning the election is a way for him to continue moving in the right direction after all he’s been through. “Being in a foster home for five years…That does something to you,” he says.

When he grows up, he wants to become a psychologist. That way, he can help people who’ve been through the things he’s had to endure. “I feel like I can do great things, I just need an opportunity to do them now,” he says. “I could easily go to college right now. The only thing holding me back is my age.” ♦