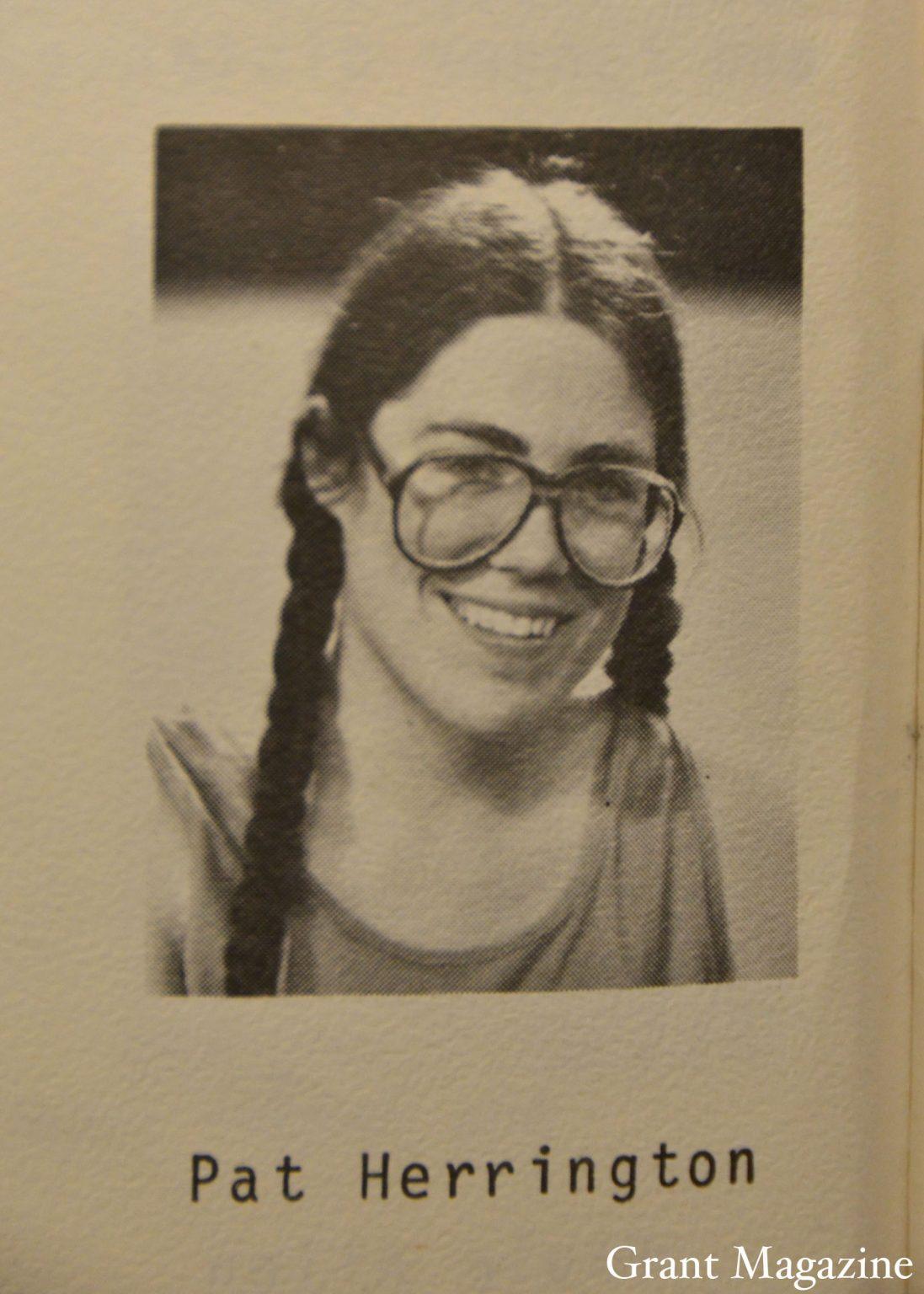

Three years ago, before she became some of her Grant High School students’ favorite math teacher, Pat Herrington did not bike to school. Her clothes were tight-fitting, her energy gone before lunchtime, her daily food intake consisting of sweets. She was also consistently angry. In her classroom, Herrington, who is known by her friends as cheerful and friendly, was frustrated.

The 54-year-old, who at the time had been teaching at Grant for five years, was unhealthy. The years she’d spent overloading on carbohydrates were catching up to her. She was exhausted, and her weight was ballooning.

“I was getting burnt out from teaching lower-level classes all the time,” Herrington says now. “It’s hard to watch kids struggle all the time. I was grumpy at home, I was grumpy at school. I needed a change.”

At the time, Herrington felt that two things needed to happen: she needed to change her schedule and teach different classes, and more importantly, she needed to lose weight.

“It got to a point where it was kind of like, ‘This can’t keep going,’” Herrington remembers. “I needed to do it for the kids at school, but most importantly, for myself.”

She hails from Athens, Greece, the daughter of American parents June and Charles Herrington. She lived there until she was 2. After that, it was Denmark for four years, then a six-month-stint in the United States. When she was 6, her family shipped back out to Maadi, Egypt, only to be evacuated back to Athens due to the Six-Day War in June 1967, when tension between Arabs and Israeli erupted into a brief spell of conflict for less than a week.

The constant relocating was the result of her father, Charles Herrington, who was a secretive U.S. Army Intelligence Agency spy – “the kind that people seem to think are only real in movies”. The secretive part of his job wasn’t for show. At one point, he was hired to track down his best friend, a double agent, and kill him. It haunted him until the day he died.

Herrington and her six siblings had no idea what he did for a living until years after his retirement. “He was probably the most intelligent person I ever met in my life,” says Herrington softly.

After her father retired from the military when she was 8, the family settled in Battle Ground, Wash., on her grandparents’ small farm. It was at Battle Ground High School where Herrington earned nine varsity letters in three years and made it to several state competitions for three years in volleyball, basketball, softball and track. Her family later moved to Beaverton for her father’s new job at Tektronix, and Herrington enrolled at Sunset High School for her senior year, where she continued to excel. She still holds the all-time discus record at Sunset by 25 feet.

“My involvement with sports has probably been the biggest thing that’s shaped my life,” she says. “I didn’t play any sports until fourth grade, when I picked up a basketball.”

She played every day, rain or shine, even popping the basketball into the dryer on days when the ball got too wet. “I fell in love,” she says.

Her passion for sports showed, as she received a full scholarship to Portland State University for basketball and track and field. But she lasted just two weeks of basketball practice until she quit the team. “It just wasn’t for me anymore,” Herrington says. “I’d kind of lost that competitive edge with basketball.”

After realizing that the school didn’t fit, Herrington left Portland State at the end of the winter term. She transferred to Idaho State University, where she continued to throw the discus, javelin and shot put. She still holds records for discus and javelin there.

Herrington was the first ever All-American athlete at the school and qualified for Nationals all four years. At one point during her collegiate career, she was in the top ten women discus throwers in the country. She qualified for the 1980 Olympic Game Trials; however, due to miscommunication with her coaches and the conflict with President Jimmy Carter boycotting the Olympics, she was unable to compete.

When Herrington was a senior at Idaho State, a friend on the softball team was overweight.

“She was going to lose her scholarship,” Herrington says. “I decided to help her out.”

Herrington organized a contest of sorts, where she and her friend would compare how many pounds they lost. For a period of six weeks, she ran 100 miles a week. She developed a grueling daily routine where she woke up at 6 a.m. and ran the mile and a half to the dance studio where she would do track workouts. Then she ran back home, ran to her first classes and then ran home again.

After that, she ran to her afternoon classes, ran home yet again and finally ran to track and field practice, where she would do all kinds of running there, and then finished with an evening run. On the weekends, Herrington would ask a friend to drop her off about 10 to 15 miles away from home and simply run all the way back.

She ended up losing 75 pounds. Her partner didn’t even lose 15.

“I realized that the teaching was fun. … I loved being at school, I loved doing school, and I just said, ‘You know, it’s a perfect place for me.’” – Pat Herrington

Herrington hadn’t counted on the consequences. By the end, she was down to an alarmingly low four percent of body fat. She contracted bronchitis and bronchial pneumonia, which persisted all the way through Nationals. Somehow, she still managed to place fourth at Nationals that year.

Her athletic achievements would continue to grow as she became the second-ever woman and first-ever track and field athlete to be inducted into Idaho State University’s Athletic Hall of Fame in 1992.

After graduating from Idaho State with a major in physical education and health, Herrington worked a series of jobs on the West Coast: bookkeeper for a bakery, advertising manager, delivery truck driver, finance manager.

“About six or seven years after graduating, it was just kind of like, ‘OK, you have to find something to focus on,’” she says. “I really didn’t know what I wanted to do at that point. I didn’t think I wanted to teach at all.”

Herrington tried student teaching at Fort Vancouver High School in 1987, but figured that she would be better suited with a job as an electrical apprentice.

That job went horribly awry when she developed carpal tunnel syndrome, which meant she had excessive pressure placed on the median nerve in the wrist. Herrington had an epiphany at that point. She was hobbled as an apprentice, but her future, she decided, needed to involve teaching.

In 1991, Herrington began her teaching career as a physical education and math teacher at Yamhill Carlton High School in Yamhill, Oregon. “When I first started teaching, I had no clue,” she says. “I was thrown into a math classroom after doing my student teaching in P.E. I just did what the other math teachers did.

“I think the second year I was there, I kind of went, ‘You know, this isn’t working.’ I needed to do something different. And one of the biggest things I did was try and make more connections with each kid.”

And she did.

She began meeting with her kids once every quarter individually, and continued to do so once she moved to Jefferson High School in North Portland. When she arrived at Grant in 2004, the philosophy stayed the same.

Her schedule, on the other hand, did not.

“The first three or four years I was here, they constantly were changing my schedule,” Herrington says. “Sometimes I’d get my schedule changed at the end of the first quarter, the end of the second quarter. I finally said, ‘I need more of a stable schedule.’”

Halfway through the 2010-11 school year, Herrington came to the realization that there were other issues she had to face. The accumulation of bad food had finally caught up to her.

“It got to a point where it was kind of like, ‘This can’t keep going,’” she recalls. “I needed to do it for myself. I needed to do it for the kids at school. But most importantly, for myself.”

Even being a phenomenal athlete, Herrington had never exactly maintained a healthy routine.

“It was just kind of like, ‘I’m not having any fun winter break, I don’t feel good, I’m eating yucky food,’” Herrington says. “It just – it didn’t work for me anymore.”

Although she had started to slim down in September 2010, Herrington went into winter break with full intentions of losing a substantial amount of weight. After asking for and receiving a more stable schedule, she went through two intensive weight-loss programs – Weight Watchers and Take Shape For Life.

Over the course of one year, Herrington lost 145 pounds.

“It worked,” she says today. “It’s the only thing that ever worked.”

Her joints, which used to ache to the point where she had to sit down, were free of pain. Her energy level, which used to run out in just a couple of hours, began to last for the entire day. And her strict and stern teaching style was being mixed more with the friendly and humorous approach.

The weight loss was easy for Herrington. The more she lost, the easier it became. And ultimately, it translated to the classroom. Her newfound energy from the weight loss would contribute to her teaching as she began to “put herself into lessons” and make connections with her students.

Most importantly, Herrington felt good.

“She has the biggest heart in the world. She would do anything. For anybody.” – Mary Herrington

She laughs now when she thinks about it, the only sign that she was ever overweight being the half-empty Coke Zero bottle resting on the edge of her desk. “It’s the caffeine,” she laughs. “I’m trying to quit by the end of the quarter.”

She’s slim now and eats five to six healthy snacks a day. Gone are the tasty Snickers bars, the over-consumption of bananas and the unhealthy loaves of bread.

Her niece, Alex Herrington, an 18-year-old freshman at Oregon State University, witnessed the change firsthand. “She’s crazy active now,” she laughs. “Every time I want to take the elevator, she’ll say, ‘No, let’s take the stairs.’ She’s always wanting to go on these hikes and looking for ways to get more active.”

“I definitely think she became happier with herself and how she looked and how she felt,” says younger sister Mary Herrington, 50. Even students noticed the difference. “There was a huge difference when she came back,” says 2012 Grant graduate Melanie Smith, who is 19 and had Herrington for two years. “She had a complete transformation. She started having more fun with us in the classroom, instead of us being all intimidated by her.”

Students walking down the halls are regularly interrogated by Herrington – what class they’re taking, how they’re doing, how math is going – and sent on their way. “She really cares about where her students go,” says senior Claire Leipzig, 17, who had Herrington for her freshman and sophomore year. “She understands what works best for them.”

At 6-foot-1, Herrington towers over most of her students and some faculty members as well. Her tall and athletic figure is intimidating, too, but her personality is quite the opposite. Mary Herrington says her students and colleagues will always benefit from having Herrington at the school.

“Pat is this big, tall, athletic woman, and that can be intimidating,” Mary Herrington says. “But really, she is an absolute teddy bear. She has the biggest heart in the world. She would do anything. For anybody. And I would imagine, for her students too. She would do absolutely anything for them.”

Pat Herrington wants to see Grant students challenge themselves more. “Kids get so caught up in the best GPA they can have instead of learning what they can learn, and that frustrates me,” she says. “I really do think that kids have a lot more success in college when they do math all four years” of high school, says Herrington.

It’s been more than 40 years since Herrington climbed a pyramid in Egypt. It’s been 23 years since she started student teaching at Vancouver High School. And it’s been three years since she lost 145 pounds.

“I won’t lie. I’d love to retire,” she says. “But the truth is, I’m not sure what I would do on a daily basis.” ♦