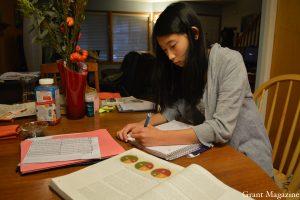

Sara Onitsuka remembers staying up past midnight in elementary school to finish a book report.

“I really didn’t want to do it and my parents were getting mad at me,” she recalls. “That’s when they told me how important school is and how much it will pay off in the long run.”

Today, Onitsuka is a senior at Grant High School and takes a challenging course load. She continues to stay up into the early hours, finishing homework. “I always do my homework,” she says. “I like to actually understand the material, not just get a good grade.”

“Right now, a lot of grades take into account sort of behavior patterns.” – Kristyn Westphal

Breanna Tarver is the oldest kid living at home, and with that comes responsibilities. She has two younger sisters and a younger brother, whom she often helps with homework at night. She also has chores. Sometimes, she says, she has to stay up late or do homework at school in order to finish.

To make the long commute from her St. Johns neighborhood, Tarver wakes up at 5:30 a.m. every morning in order to catch the bus an hour later. A little over an hour and one bus transfer later, she reaches Grant.

Last November, after her sister was diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes, mornings and getting to school on time became more of a struggle for Tarver, who had to talk to her first period teacher about the difficulties of getting to class. She has to help her sister with testing her blood levels every morning and planning out her meals. This year, she says, they’ve settled into a routine, but getting to school and finishing homework is much more difficult for her than for other Grant students.

In the end, her family situation counts as a strike against Tarver when it comes to how students are graded. The same idea has been repeated for years, beginning as early as elementary school. A concrete path of success has been emblazoned in the collective minds of many kids: get good grades by working hard and staying organized. The reward? Go on to college and find a career that intrigues you and pays good money.

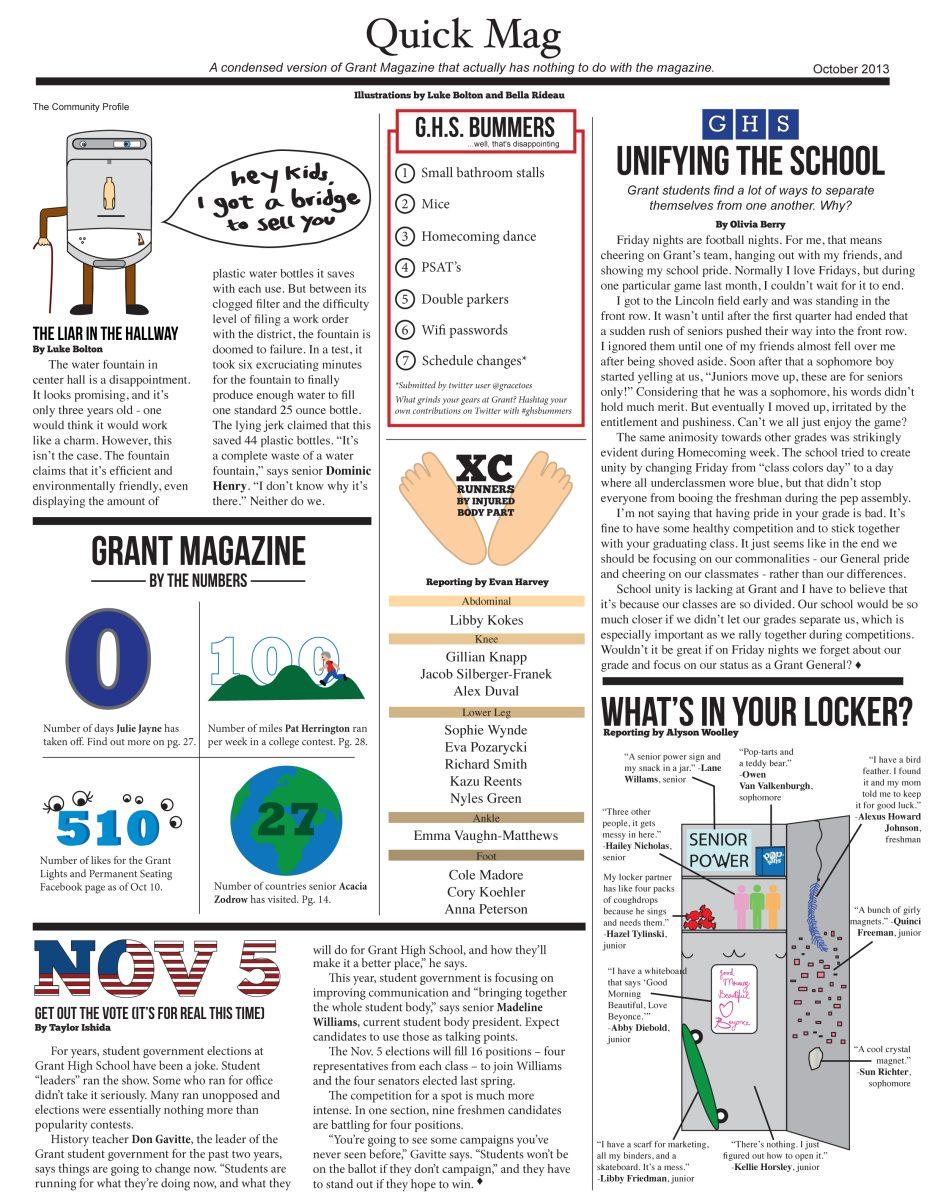

However, two years ago, a bill in the Oregon Legislature was passed that calls for a major shift in the way we know grading, and it’s charted to go into effect this fall. Some experts say the new approach to grading – one that gives educators hope of solving issues as difficult as the achievement gap and low standardized test scores – has been tossed around by school officials in Oregon for several years.

It’s called proficiency grading and the implications of it would change the landscape of school and grading, for better or for worse. So how does it work?

In the past, the way students accumulated points in each class was by scoring well on tests, quizzes or papers, which all average out to a certain grade point average. Points were earned in a variety of ways, whether through extra credit, homework assignments or timeliness.

According to an e-mail sent out to all districts in February by Heidi Sipe, the Oregon Department of Education’s assistant superintendent for the Office of Educational Improvement and Innovation, things are changing. Meeting assignment deadlines and participating in class could be wiped clean from student grades or be represented in a separate grade.

“Schools and districts must also adopt a grading system that clearly distinguishes between academic and behavioral performance,” Sipe’s email says. From now on, students will get a separate grade once a year that indicates if they are “becoming proficient in the standards” of their grade level.

Grant Vice Principal Kristyn Westphal says the new system allows some discretion. “Right now, a lot of grades take into account sort of behavior patterns,” she says. “Did a student turn something in on time, for example. Were they penalized for turning it in late? That’s not really measuring the student’s abilities.”

So will the new grading system actually represent students more fairly in the eyes of colleges and post-secondary educators? Or is it a system that will be too soft on students and allow them to make excuses? No one knows for sure.

A recent article in The Oregonian drew attention to the downward trend in test scores across the state. This year, the rate of juniors in Oregon who wrote essays that “meet” state standards dropped seven percent from last year, settling at a less-than-satisfactory 60 percent of all juniors.

But more students at schools like Grant seem to be improving on their grades. At Grant last year, for example, the number of valedictorians reached a record high of 23 students. All had 4.0 GPAs and were seen as educational ambassadors of the school.

Does that mean students who get good grades under the old system smarter? And does that translate over once they get to college?

Sandra Seppalainen is a 2012 Grant alumna who is in her sophomore year at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology. At Grant, she was the shining example of academic success after skipping two grades in middle school at Portland Public School’s ACCESS Program. She was a celebrated valedictorian. Yet, despite her successes in high school, her first semester at MIT, she says, was definitely a shock in terms of workload and rigor.

“Some homeworks are really, really focused on problem solving, so you’ll learn some concepts in class and you’ll have to apply those in a completely different way,” she says of the MIT curriculum, something that she wasn’t asked to do much of in high school.

She says a proficiency grading model in high school “definitely” could have helped her to be better prepared for college. “That’s all they grade on in college. There’s no real busy work. Most of my classes are 40 percent final, 40 percent other tests, and 20 percent homework or participation,” she says.

Many educators are looking for ways to make sure grades are a better indication of what students know, and they’re calling for a change in the grading scale. If the curriculum were changed to be less about behaviors like timeliness, and more about knowledge through testing and meaningful assignments, then students would be better prepared, they argue.

Carol Campbell, Grant’s principal, believes the traditional grading scale is not an accurate enough representation of a student’s knowledge because it’s just adding up numbers based on a variety of assignments that might not even be useful.

In some classes at Grant, students earn so many extra credit points that they can fail the test but still pass the class “because the test is not a large enough percentage maybe of the overall total points,” says Campbell.

In his freshman year at Grant, now-junior Eli Boudouris didn’t have to take the final in his Spanish class after earning enough participation points. Boudouris found the point system set up by his teacher, Richard Fisher, actually helped him to grow as a Spanish speaker. “It makes you talk in class, listen and participate,” he says.

In some proficiency grading models, participation is seen as a behavior, and it’s either included in a separate grade or not included at all. Students like Boudouris would no longer feel the need to speak up in class and language classes could take a hard hit, some say.

Anne-Marie Reid, a French teacher at Grant, focuses heavily on participation in her classes. All the work her students do in class, written and oral, including partner activities or talking in French during group discussions, consists of half of their final grade.

Demonstrating proficiency in languages makes things tricky, some say. While participation could be coined as a behavior and not a true indicator of proficiency, Reid agrees with Boudouris that participation is an essential part of becoming well versed in a language. “When you’re participating in a language class, it’s your opportunity to demonstrate your proficiency with the basic vocabulary and skills that you’re working on,” she says.

The matter is further complicated by a student’s home situation. For Tarver, finishing homework is a challenge because of her role in her household. If her grade was based on tests rather than showing up on time or just finishing the homework, then she would have a shot at being on the same level as more accomplished classmates.

Tarver says she could see proficiency grading helping her out, saying that sometimes people are busy and “they couldn’t really do their homework…so maybe they could at least give us another day.”

For years, some have advocated for giving money to students for getting good grades. But just how much and where the money would come from are two vexing questions for this approach.

Campbell argues that by offering money, another policy that some school districts across the nation have tried, you’re only rewarding the outcome and not taking a full-picture view of the situation.

“Money isn’t going to solve the problem of a student that is taking care of several younger siblings at home every night and doesn’t have an opportunity to get their homework done,” she says.

She wants to see a leveled academic playing field that removes the focus from off-site assignments to more assessment-oriented curriculum. That, she says, would make the achievement gap shrink.

Proficiency grading appears to be the perfect method to level the field. It cuts out extraneous assignments some students don’t have time for and weighs heavily on what students know, setting them up for a better future.

But many doubt it will live up to its promises.

Nancy Schaumberg is a Grant parent with an education background who has seen the ups and downs of grades. “With proficiency testing, I can appreciate the idea of wanting to make sure students are competent,” she says.

However, she believes in a full package. Students also need the life skill set that comes with homework and clear deadlines. Schaumberg sees the testing piece as important but doesn’t want the other aspects to be thrown to the side. “Students may be able to master the skills required, but if they can’t apply them in the real world, it doesn’t matter,” she says.

Onitsuka agrees that homework is still important and helps her to understand the material in her classes. Although she goes “through it more slowly,” which often leaves her up past midnight, she feels it helps her in the long run when it comes to her grades.

She was openly surprised at the possibility of homework and other behavioral tasks not factoring into her grade. “I’ve heard of colleges not giving much behavioral work, but in high school we still need deadlines. We still need guidance, otherwise we’ll just slack off,” she says.

Grant math teacher Susan Shea sees proficiency grading as a good idea – but only in theory. She points out several key flaws. Like Onitsuka and Schaumberg, she agrees late work penalties have their bonuses. She says of removing them: “I think that sets people up for the wrong way of thinking about what due dates are.”

Not to mention the pressure it could potentially put on teachers. “It’s a grading nightmare for teachers,” Shea says. “All 180 kids turn in all of their late work all on the last day before school ends or the last day of the quarter, and now can you really realistically grade all of that?”

Angela Hubbs, assistant director of curriculum for PPS, says there’s still a “dialogue” happening, even at a policy-making level. “The law is really trying to move towards making sure that … the grade a student earns in the class reflects what they actually know and what they actually can do,” she says.

This year, she says, high school administrators and teachers are scheduled to receive professional development on proficiency grading. How they choose to apply the law to their school, while staying within the restrictions of the bill, is up to them.

“We still need guidance, otherwise we’ll just slack off.” – Sara Onitsuka

Some school districts have already gone full throttle into proficiency grading. In Forest Grove, homework and behavior patterns are only ten percent of a student’s grade since they’ve moved to proficiency grading. Students also can retake tests as many times as they want.

Campbell believes students should be able to fail first in school. “This isn’t the real world. This is about academics,” Campbell says. “It is about learning. So in learning to really learn something you oftentimes have to fail first. If we’re not going to allow students to make mistakes and to essentially fail in some areas, then we’re really limiting their ability to learn.”

The issue of grading is full of complexities and uncertainties. A student’s home situation, ability to learn, and habits all must be considered. Coming up with a generic system that encompasses all students is never simple.

It’s unclear right now what changes administrators at Grant will make and what effect it will have on students.

But they certainly have their aspirations.

Says Westphal: “I hope that as we move towards proficiency that we would actually be seeing all students with As and Bs because it will mean something different, so if we’re really moving towards measuring what students know and can do, and we’re teaching well, most students should be earning solid grades.” ♦