When you walk into Wieden+Kennedy, you don’t see awards. You won’t see the latest ads crafted by the infamously creative W+K’rs who inhabit the olive green building in Northwest Portland. The first thing that greets you at the door, besides the eight-foot-tall beaver sculpture, is a wall full of goofy portraits. There are 409 total, each an expressive testament to the vibrant culture of – arguably – the best and most creative independent advertising agency in the world. Somewhere among the framed faces there is a man with a dark goatee and a cigarette between his fingers.

Today, Dan Wieden’s facial hair is stark white and the nicotine is long gone. He descends the building’s stairways more patiently than he once did, perhaps, but he’s still got energy to match that of the young creatives who walk beside him. Hellos and head nods meet good afternoons as he meanders through the 700 body strong agency headquarters. His office is on the sixth floor, two floors above the “Fail Harder” wall that always stops him in his tracks. It’s not far from “The Nest,” a branch-surrounded, cushion-bearing meeting room perched upon support beams that stretch the length of the building.

The symbolism brings beginnings to mind, not that Wieden remembers much of his own. “I was inside my mother,” he explains matter of factly. Wieden’s father, Duke, was 6,000 miles away when he got the message. He was part of the first wave of U.S. Navy soldiers to hit the ground at Okinawa in 1945. His friend, a signalman offshore, sent the memo: “It’s a boy.”

After the war, Wieden’s dad and grandfather built a small house on a two-acre plot near Southeast 122nd Avenue and Holgate street. At the time, the area was practically countryside. Three-year-old Dan shared a room with his infant brother, Ken. He laughs about it now, but one day that nobody recalls clearly, he broke his brother’s collarbone. At least he thinks he did. Both boys had been playing in Ken’s crib when the younger one ended up on the floor. The crib walls were too high to climb, suggesting that Dan had something to do with the accident. “He’s been making me feel guilty ever since,” jokes Wieden.

Seven now time-clouded years later, the Wieden family moved to the Irvington neighborhood in Northeast Portland. Not long after, Sherrie Wieden was born. “We were so happy to have a sister,” Wieden says. “We went around the block telling everybody: It’s a girl! It’s a girl!”

As they were growing up, Wieden and his siblings did the things that seemed to characterize the post-war, middle class American childhood. Family trips to Disneyland. Playing football in the street. The most fun they had, Wieden says, were the dirt clod and horse-chestnut fights they had with various neighbors. “It would be all out war,” he says. One house over, the Campbell family had seven boys. All of them were athletes. “Why we picked a fight with them, I’ll never know,” Wieden says.

His mother, Violet, was supportive during Wieden’s early days. “She sort of followed all of us kids,” he says, “whether it was tap dancing lessons for my sister, my brother’s various sports that he did.” One memory that sticks out for Wieden is of him and mom working on a school project together, building a 3D map of South America. She was a very involved parent and ended up as head of the PTA at Irvington School, where all of the Wieden kids attended.

From an early age, Wieden became interested in drama. “It’s kind of embarrassing,” he says, recalling elementary school plays and nursery rhyme pantomimes. At one point, the young Wieden was “mayor” of Irvington School, a tradition that no longer exists. “I feel like a complete artifact,” he says now.

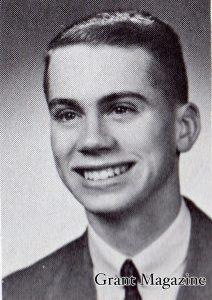

Both of Wieden’s parents graduated from Grant, so his father served as a reference point when he started freshman year. “I think he did much better than I did in high school,” says Wieden.

“I wasn’t a great student. I was really curious, but nobody was going to put me into a Mensa group.” -Dan Wieden

Wieden says he was useless in land sports, something at which his dad had excelled. Add water, though, and Wieden was right at home. He swam with the Amateur Athletic Union throughout high school and joined Grant’s swim team senior year.

He didn’t exactly “fit in” during his time at Grant, and he didn’t necessarily want to. “We used to call them socias, which were the people who had their act together and were more sort of normal people,” Wieden remembers. “Then there were the rest of us.” He explains that he liked “the odd folks” who were interested in weird things; the people with strange senses of humor – or no sense of humor. The more idiosyncratic, the better.

As an upperclassman, Wieden helped start what he now calls an “antisocial club.” Back then, they called themselves Alpha Theta Troll. One day, two members decided to stand right off campus and distribute a pamphlet making fun of the current student body president and “various other things about the school.” They were suspended.

Wieden, who describes his teenage self as “cautiously rebellious,” was furious at the breach of free speech. Along with some other friends, he picketed the school, much to the interest of local news agencies. “My mother and my father were not amused,” says Wieden, “but to this day I think we had the right to do that off campus.”

The best part of high school for Wieden was theater. He landed major roles in four productions at Grant, including The Man Who Came to Dinner and Harvey. He remembers constant arguments with the tall, curly haired drama teacher, Lloyd Carothers, but found something special onstage. It allowed him to explore different personalities, to find his own voice.

Then, of course, there were the ladies. “Most of the plays I had the chance to kiss girls on stage,” says Wieden. “We thought we were hot shit,” he adds, referring to his group of thespian friends at the time.

But he was no stranger to the ups and downs of adolescence. “Everybody in high school feels slightly insecure to really insecure,” he says. “We handled our insecurity by being sort of social dropouts.”

Despite his love for acting, Wieden says that he was intensely self-conscious. Because he was an introvert, Wieden’s parents often worried about him. He remembers reading for hours on end in the sand dunes of the Oregon coast as a teenager. Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer was banned in the United States at the time because of its straightforward sexual obscenity. It was one of Wieden’s favorites.

Wieden, a shy guy who loved the stage and swam every day, had little to no clue what he wanted to be when he grew up. When he went to the University of Oregon, swimming and theater phased out of his life. He worked for Shell Oil for a while and graduated with a degree in journalism in 1967.

Eventually, Wieden landed at Georgia-Pacific, a conservative paper products company. Although he depended on the job to make a living, he hated working there and intentionally created problems, attempting to get fired. “I tried for five years to get kicked out,” he recounted at a recent conference for small advertising agencies. “When they finally obliged, my personal world collapsed.”

In the parking lot that day, Wieden was forced to take a hard look at his life. “What kind of idiot decides to act up, create crisis after crisis and force his employer to do what he didn’t have the balls to do himself?” he asked the crowd of admen at the conference. “I felt worthless.”

His wife, Bonnie, was folding diapers when he came home jobless. At the time, they had two kids and another coming soon. “Something will turn up,” she said calmly, a seemingly absurd remark to make when you suddenly lose your family’s entire income. According to Wieden, her response flipped his world right side up. Her words gave him “the freedom to fail.”

With his newfound liberty, Wieden played around with freelance writing and soon joined the advertising giant McCann-Erickson, the agency that handled Georgia-Pacific’s marketing agenda. His father had been in the advertising business, so it was somewhat familiar territory.

Wieden’s family, with four children now, moved out of the city and into a house on five acres in Dundee, Oregon. “We had every critter God ever made,” says Wieden. Horses. Chickens. Rabbits. You name it.

Cassie Wieden, his youngest daughter, remembers building forts in the woods near the house, horseback riding and biking down to the dime store to buy candy. With her three siblings and the occasional cousin, there was never a playmate shortage. “To me it was really sort of a utopian childhood,” she says. “Pancakes and John Denver on Sunday mornings.”

Dad was always present. He made time to teach the kids card games and take family road trips across the country. The best thing about him, says his daughter, was his endless love for Bonnie, and vice versa. The passion was a constant.

Bonnie was a country girl, so Dundee was nothing new. Being the city boy that he was, though, Wieden had to adapt. His biggest self-proclaimed blunder was buying a milk cow. “I thought: ‘Oh, this will be terrific. We’ll get free milk!’” The only problem? Milk cows must be milked. Every day. If you want a vacation, you can’t exactly leave a note on the neighbor’s door asking them to squeeze your cow’s udder. “I had no idea what I was doing,” Wieden says. “I’ve never had any idea what I’m doing in life.”

The same notion presumably applies to the birth of Wieden+Kennedy.

McCann-Erickson closed its Portland office when Georgia-Pacific moved out of the city in 1981. By that time, Wieden, 36, had become friends with David Kennedy, a Chicago ad man who also worked at McCann. They co-founded their own agency on April fools day, 1982.

Operating out of a downtown basement, the newborn Wieden & Kennedy (later changed to Wieden+Kennedy) was penniless. They did, however, have quarters, which they used for the payphone down the hall. They couldn’t afford their own phone line. There were four employees, including Kennedy and Wieden. “Our dream was that maybe we could have a dozen, maybe eighteen people and just do our thing,” says Wieden. “That was the extent of the dream.”

But that vision didn’t last long. After they tracked down Nike co-founder Phil Knight and convinced him to give the young agency a shot, Wieden coined the sportswear company’s most renowned slogan: Just Do It. The campaign put the young agency – and Nike – on a turbulent one-way flight to success. “It’s like you went out surfing one day and the wave you got on just kept getting bigger,” Wieden says. “You go: ‘I’m not jumping off this sucker.’”

Soon, more and more companies were seeking out W+K to create and reinvigorate their brand images. Honda. Coca-Cola. Microsoft. Some campaigns worked perfectly. Other clients didn’t mesh well with Wieden+Kennedy’s way of doing things.

Subaru was a notable failure. The Japanese auto company was bruised by the recession and reluctant to bet the brand on the big ideas of a small agency on the West Coast. W+K opened an office in Philadelphia, near where Subaru of America was headquartered, to work more closely with their client. The branch was closed two years after its inception, relationship soured.

At about the same time, Nike decided to get a better foothold in the European market, so they started running more of their commercials in Great Britain.

But the new audience didn’t quite understand the nuanced advertisements. Nike’s persona didn’t quite click with the Brits. Out of the cultural confusion sprang W+K’s office in Amsterdam, an agency outpost that could use local knowledge to forge ads that would resonate with Europeans.

Then an office popped up in Manhattan. Then one in London. Then Tokyo. Shanghai, New Delhi and São Paulo were on the way.

How did it feel to start expanding so rapidly? “Scary,” Wieden says. He remembers thinking: “I’m so over my (expletive) head.” And that’s where his days in Grant’s theater room came into play. “Both Kennedy and I were acting,” he says. “We acted like we knew what we were doing.”

For a guy who’s been playing a part for 31 years, Wieden has done remarkably well. The agency as a whole has truckloads of awards. They’ve been named “Agency of the Year” multiple times by at least four serious organizations. Advertising Age first gave them the title in 1991, and there is no end in sight for the trophy collection.

There is somewhat of an end for the trophies themselves, though. At one point a Wieden+Kennedy employee rounded them all up and spray painted them hot pink. That’s kind of their collective attitude with showing off: do it with good taste.

Last year Wieden himself was awarded the Lion of St. Mark award from Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity, an annual event recognizing the best work in the global advertising industry.

D&AD, which stands for Design and Art Direction, is another institution that is hellbent on elevating the fields of design and advertising by rewarding those who make a difference. They presented Wieden with the President’s Award for being one of the most innovative players in the ad game. In response, Wieden said: “This is not about me. What you’re honoring here actually is a group of people who came together in the wilds of the Pacific Northwest and did outrageous work for outrageous clients and had a lot of fun doing it.”

The Art Director’s Club inducted him into their hall of fame. CLIO gave him the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award.

Adcolor bestowed him with the Catalyst Award for pushing diversity in the industry. Out of all the awards, Wieden says it’s the most important one he’s ever held.

Walk into W+K’s office and you’ll be faced with people of every age, shape, color and every other adjective that describes a human being. Diversity is a crucial layer of W+K’s way. The more perspectives crammed into one building, the better. And while you’re at it, you might as well make that one building into a self-contained dream world.

Once you climb the stairs past the wall of funny faces, you enter the rather spacious, well-designed belly of the beast. Dance past the towering totem pole and up a flight of stairs and you’re in the atrium, the heart of the building where “good sized” events are held. Wooden bleachers provide enough seating for all-staff meetings, lunchbox concerts and the occasional inter-agency boxing tournament. On the fourth floor, there’s a mural made of about 119,000 clear (and one red) plastic pushpins that leaves “Fail Harder” spelled out in the negative space.

Work at W+K is hopelessly intertwined with play, but that’s the idea. It yields some of the best work in the ad industry, from Levi’s Go Forth campaign to The Old Spice Guy. “We have tried to create a culture that helps people live up to their potential,” says Wieden. “That feels like our mission at the end of the day, more than advertising.”

Grant’s Career Coordinator, Madeline Kokes, worked at Wieden+Kennedy for 11 years before coming to the school. She’d been in the advertising business for 10 years before W+K, working for various agencies in L.A. It hardly prepared her for Wieden+Kennedy. “I thought that I had died and gone to heaven,” she says. Within a month of getting hired, she was in Western Europe, constructing a magazine ad for Nike’s international account.

What struck her most upon arrival to the agency was the people. “You have to have a little bit of the whack factor,” she explains. “There’s a very special type of eccentric creative person that works at Wieden+Kennedy.” She remembers the tight community of employees who seemed to never stop working and hung out together whenever they could. “I think he’s a visionary guru,” she says of Wieden. “He creates an environment where you can be you.”

Kristen Clark left Wieden+Kennedy last February after working in the Portland office for nearly a decade. As the Global Director of Human Resources, she worked closely with Wieden. She was constantly exposed to the outlandish ideas that seem to pour out of the man by the barrel.

Sometimes Clark had to push back. She was in charge of policy and guidelines, a rule enforcer. Wieden, she says, “doesn’t like structure.” One of his many mantras is “chaos breeds creativity,” a paradigm that has served W+K well, especially in the realm of brilliant idea production. In one instance, Wieden tried to get ponies to deliver the agency’s mail every morning. Health regulations, brought the thought to a quick end.

Aside from keeping the creative flame tended at the agency, Clark says Wieden has a “huge heart.” His compassion showed itself bluntly when the economy tanked in 2008. He refused to lay off a single employee, carrying nearly 100 men and women on the payroll through the storm. “He wasn’t going to turn people out into this crappy job environment,” says Clark. That type of gesture on that big of a scale is practically unheard of.

“He’s amazing,” Clark says. “For someone who’s worth a couple hundred million dollars – just throwin’ that out there – you would expect a different sort of person.”

In 1996, Wieden started Caldera, a non-profit art and environmental camp for underserved youth. It was the crystallization of a shared vision between him and his daughter Cassie. She wanted to help kids experience nature. He wanted to help them experience art. All four of his children pitched in, contributing horseback riding lessons, reading programs and all the other cogs and gears needed to keep Caldera in forward motion.

Julie Mancini, Mercy Corps’ action center director, was executive director of Caldera from 2000-2003. She was one of the first people heavily involved with the camp whose last name wasn’t Wieden. “Every nonprofit starts with somebody’s idea,” Mancini says. “Your goal is to just keep making the family around that idea bigger and bigger and bigger.” Now Caldera isn’t a Wieden family thing, it’s a Caldera family thing.

The campground itself is located on Blue Lake, near Sisters, but serves kids from Portland as well as Central Oregon. Unlike many youth programs, Caldera sticks with students year-round, acting as a constant support structure that helps “campers” stay on track at home and constantly express themselves positively.

Aasha Benton goes by Ooh La La at Caldera, where she’s been a youth advocate – Caldera’s term for camp counselor – for three years. When Benton was a camper herself in 2005, she knew Wieden as Papa Bear. It’s what he goes by during the 26 days every summer when he goes missing from W+K to spend time with the kids at Caldera. “He eats every meal with us,” Benton says. “He is always smiling and talking with students.”

Every session, the kids share a camp-wide catchphrase that becomes part of everyone’s vocabulary. “My favorite was ‘All Camp Dance Party,’” Benton says. One person would shout it and start the chant, causing everybody at camp to stop what they were doing and bust a move.

“Through the arts, these young people find their voice,” says Wieden, “and when you find your voice you have a place in the world.” You don’t have to become an artist, he explains, because unlocking your creative potential works its way into every aspect of your life. Year after year, Wieden watches as the campers, who almost always come from tough home situations, realize that they have a seat at the table.

Wieden is still chairman of Wieden+Kennedy, but he is starting to spend less time at the agency office. Like David Kennedy, who retired 15 years ago but still stops by a couple times every week, it seems like Wieden is becoming more of an icon than a boss man, a legendary figure who embodies the creativity, independence and humility that W+K molds itself around.

And it looks like the agency will hold true to those values for a long while, because Wieden+Kennedy will never sell out. The freedom that fuels the agency’s groundbreaking work wouldn’t be possible if big business-minded shareholders dictated how Wieden+Kennedy runs. That, Wieden insists, will never happen. “He’s had calls to buy Wieden+Kennedy,” says Clark, who still keeps in touch with him. “He literally just hangs up the phone.”

The agency is in good hands, although Wieden will never truly leave, which gives him a little time to kick back a bit. He was recently remarried after several years of recovery from the loss of his first wife, who died in 2008 of a heart attack. He’s carved out time to travel the world with his new wife.

Wieden continues to breathe passion into Caldera, which is gaining national attention for it’s innovative approach to helping disadvantaged youth.

There will be no end to Wieden’s waterfall of radical ideas, rest assured. But now, says Clark, “He’s finally enjoying the fruits of his labor.” ♦