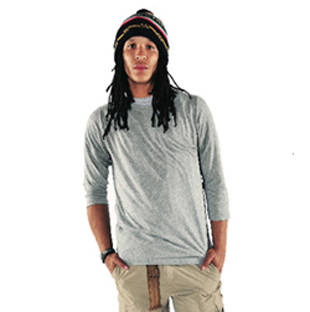

Grant High School senior Zackery Ratliff sits in an empty classroom long after the bell has rung and students and staff have left the building.

Kelley Allen, Ratliff’s astronomy teacher, stands before him and breaks it down: you’ve put this off and now you’re paying the price. She looks at her watch and sees she’s late for a faculty meeting. Hurriedly starting the film on space that Ratliff missed earlier that week, she gives him a worksheet to follow along and answer questions before she scurries out the door.

Ratliff watches the 50-minute film uninterested. When the television screen goes black, his paper remains blank.

Students who slack off their freshman, sophomore and even junior year eventually suffer the consequences. For some, it means taking a full schedule of eight classes as a senior, or even night school courses to make up for classes they failed in previous years. While their other senior friends are off having fun, they’re cramming for a proctored exam, or rushing to get to Benson on time for the Portland Evening Scholar’s program, which allows students to recover and improve grades in main subject areas.

For many freshmen at Grant, the transition from middle school is tough. More freedom in high school means more responsibility. While some are eager to take the next step, others fall quickly into poor study habits that only end up hurting them come graduation.

Zachary Person, one of Western Oregon University’s admission counselors, is willing to work with students who struggled in high school. When looking at transcripts of applying seniors, Person looks for a student who is able to address and remedy academic deficiencies. He frequently sees students who struggle in their freshmen year and sophomore year before resolving their habits.

“Not everyone may be in their ideal learning environment, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have the tools to be academically successful at the university level,” he says.

Kristyn Westphal, Grant’s curriculum Vice Principal, has encountered many struggling students in her short time at Grant. She sees many factors that influence these struggles, such as family issues, health problems, lack of organization, and students who fall behind and get overwhelmed. When the problems escalate, she meets with students, families and counselors to figure out the best path for recovery.

“I think the struggle is normal and natural,” Westphal says. “The most important thing for students to know is that they have to speak up for themselves so they can get help.”

Freshman English teacher Kris Spurlock has instructed many freshmen over the years and has seen the struggle firsthand. “Many freshmen don’t fully understand the connection between consistently completing assignments and academic success until they are in an academic hole, which is tough to get out of,” she says. “In the end, they create more stress and effort for themselves, trying to catch up, or even pass their classes.”

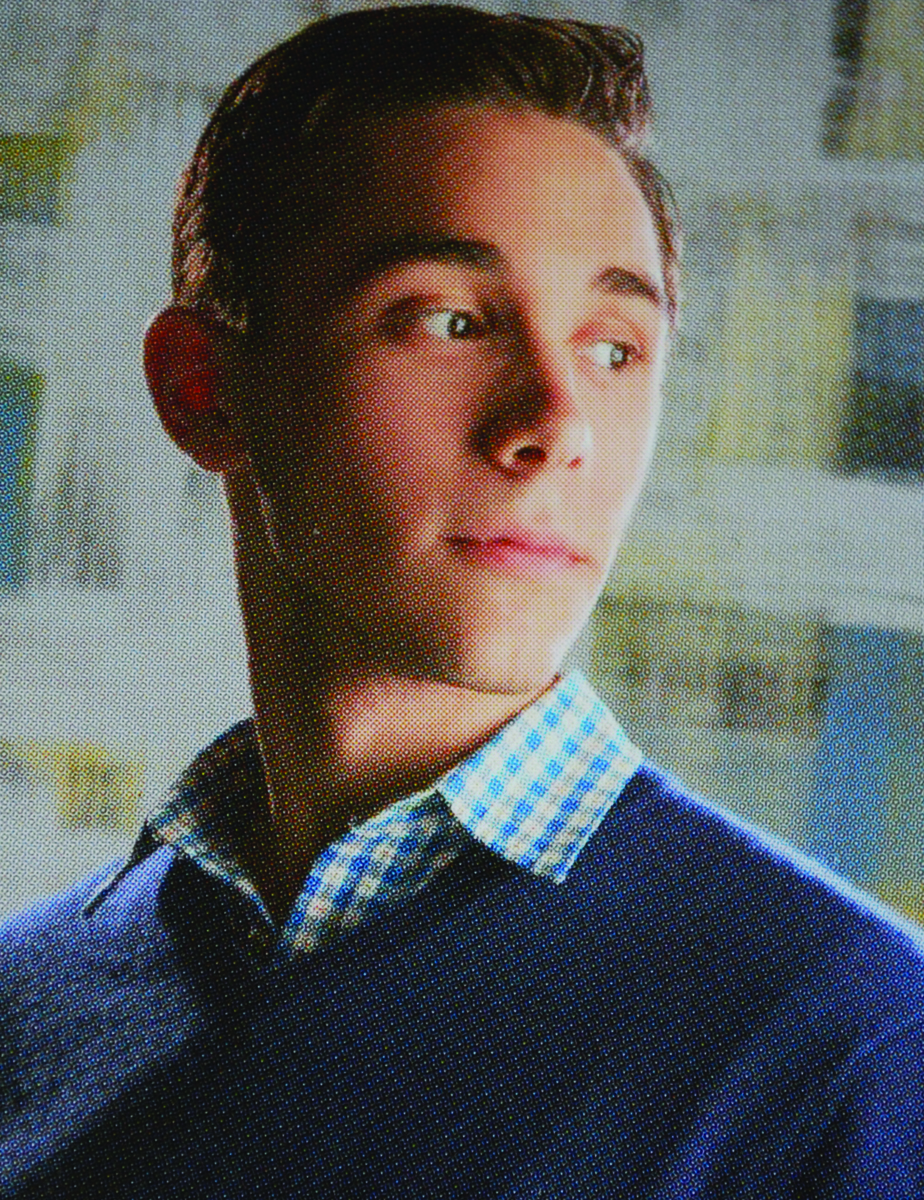

For senior Mig McLaughlin – who spent his middle school years at ACCESS Academy, an accelerated program for Talented and Gifted students – the pressures of high school hit hard. At ACCESS Academy, McLaughlin recalls a fair amount of “hand holding” from teachers and staff. But once at Grant, no one was there to guide him, and he quickly became overwhelmed with his workload. By the end of his junior year, McLaughlin’s grades were well below average.

For senior Mig McLaughlin – who spent his middle school years at ACCESS Academy, an accelerated program for Talented and Gifted students – the pressures of high school hit hard. At ACCESS Academy, McLaughlin recalls a fair amount of “hand holding” from teachers and staff. But once at Grant, no one was there to guide him, and he quickly became overwhelmed with his workload. By the end of his junior year, McLaughlin’s grades were well below average.

He took high-level classes his freshman year: pre calculus, accelerated sophomore English, and a semester of AP Biology; and was only enrolled in one regular freshman community class.

McLaughlin wasn’t used to having to work very hard to understand concepts and get good grades, and he hadn’t developed proper study skills. He neglected his homework because he thought it wasn’t important, and after missing a month of school during the fall of his freshman year due to surgery on his arm, he fell even more behind and lost interest.

Things started looking up the first semester of McLaughlin’s sophomore year. He was able to manage his stress in a positive way, but he struggled with sleeping problems throughout second semester. Most nights he would be up until 5 a.m. and still attend class the next day in a state of delirium. He even recalls points where he would be so tired that he would fall asleep during a test.

By junior year, his lack of sleep had fully caught up to him. He found it impossible to attend class, and if he did, he would show up only in the afternoon.

McLaughlin’s friends, who all did well in school, were able to get their work done before having a social life. He found himself pushing his work off until later so he could be involved in activities and spend time with them. One night, he witnessed his friends get sick from drinking and they ended up vomiting everywhere. He realized because he wasn’t making the conscious effort to do what he needed to do, and he might end up going down that path if he didn’t make a change.

“It was all contributing to a serious lack of control over my life,” he says.

McLaughlin struggled finding the ability to motivate himself and work towards improving things every day, but he didn’t want to waste his potential and managed to turn Fs into As.

With less than a month of high school left, McLaughlin has committed to attend Portland State University Honors College in the fall, but it wasn’t just as easy as submitting a general application. His underclassmen mistakes hurt his 2.5 cumulative GPA, so McLaughlin had to complete supplemental essays in order to even be considered for admission. He didn’t expect to be accepted into the Honors program, but thinks they must have seen his improvement as “inspiring.”

“It’s not where I could be or where I would like to be, but it’s a better start than what I expected.” McLaughlin says.

Ratliff recognizes the key factor in his lack of motivation is procrastination. Unlike his other senior friends who only have four or five classes, this year Ratliff is taking twelve: eight during the day, three in night school and one online. It’s hard for him to watch as his friends enjoy their senior year while he struggles to balance an extra workload of academics with other activities.

“When I do go to class, it sucks having to see people posting pictures and talking about things and I just have to watch from outside basically,” he says.

For many, fear of missing out is triggered by social media, causing teens to be more focused on what they could be doing rather than what they should be doing, such as schoolwork.

Counselor Tearale Triplett believes social media can be a very damaging way for how kids assess themselves: when you’re constantly looking at what your friends are doing, then looking at yourself, you might feel as though you’re not as good of a person as them because you can’t be involved.

“I just hate to see kids that get too caught up in how they’re perceived socially,” Triplett says.

Ratliff traces his struggles back to fifth grade when he found himself not doing the work. By middle school, he was hanging out with the “wrong crowd.”

“I didn’t know how to write a paper freshman year,” Ratliff remembers. “I had no grasp on what high school was going to be like.”

It only got worse from there. Ratliff struggled with grades and attendance throughout high school, landing him where he is now.

This year, three nights a week, Ratliff gets out of night school at 9:00 p.m. and waits for the bus for half an hour, putting him home at 10:15 p.m. If he can focus, he does homework for a few hours, finally getting to bed around 1:30 a.m. His busy schedule and lack of sleep make it hard to get up and go to school in the morning, so from time to time, he doesn’t.

“It sucks sacrificing school for my sleep, but sometimes I feel like I wouldn’t be productive at school if I had gone,” Ratliff says.

Ratliff feels high school is all about choices. “You have three choices: grades, sleep and a social life. And you can only pick two.” He explains that if you focus on grades, you lose sleep. If you go out with friends, your grades suffer.

His parents see potential in their energetic son, but wish he would apply himself more effectively to his studies.

Family members have offered up simple advice. “You just have to sit down and do the work,” they say. But Ratliff argues it’s not that easy. High school comes easy for some, but for others, the learning style doesn’t compute. He believes high school is not made for everybody, himself included. For Ratliff, high school never provided anything interesting or anything he cares about enough to work hard for.

Senior Eleanor Larsen has identified a common trend with individuals in her classes over the years. She sees students slacking off in classes where their teacher fails to make their curriculum relevant to the outside world. Students can turn in assignments on time in one class that they find engaging and relevant, but that same student might fail to do work for months at a time in another class that they deem unimportant.

“Those are the kids who put things off and by the end of the semester are making everything up, coming in looking for work and extra credit,” Larsen says.

Ratliff emphasizes that although his grades might not reflect it, he loves learning, and he embraces its importance. He sees high school curriculum as a “cookie cutter way of learning.” Everyone is supposed to learn the same, but not everyone does.

His advice? Buckle down early and by senior year, you’ll be able to enjoy it and hang out with friends, doing everything that high school is meant to be.

Looking back to freshman year, McLaughlin says he always expected to graduate, but didn’t see himself going to college.

Now, he regularly attends his six classes, and if he misses one, he makes sure to speak with his teacher in order to make it up.

When asked what advice he has to offer, he keeps it short and sweet: “Never expect that your success is given; you have to earn it.” ♦