When the members of Grant’s 2012-13 Constitution Team first met last spring, they knew the penultimate goal was to triumph over crosstown rival and defending national champion Lincoln High School at the state competition. They knew the ultimate achievement lay in attaining the position of best in the nation. They wanted to win.

After last year’s devastating loss at state to Lincoln, Grant social studies teacher and Con Team advisor David Lickey recalls how the disappointment clouded the remainder of the school year. The students had given the competition everything they had, but they lost. As his focus shifted to the coming year, Lickey remembers feeling: “The only way to make that make sense is to beat them the next time.”

The current members of Grant’s Con Team took last year’s disappointment and turned it into motivation. They spent hours training and preparing for competitions. They met with a core group of volunteer coaches every Wednesday night and for four hours on a number of Sundays. Students on the team also met with their specialized units to focus on their varying areas of study.

Grant senior Dylan Tingley says of it all: “It has been one of the most enriching experiences of my high school career.”

“It is a sacrifice,” says senior Morgan Grover. “It starts out as work and it turns into fun.”

The work paid off. In January, Grant defeated Lincoln at the state championship. And all the research, drafting and redrafting of prepared statements has led the 34-student team to Washington, D.C., where it is currently competing for a vaunted national title. The competition began April 27 and finishes up two days later.

The national Constitution Team program, called “We the People,” was created by the California-based nonprofit Center for Civic Education. For years, it was funded by Congress. But federal funding cuts in 2011 made the program’s future uncertain. The center has managed to find enough private funding to host the national competitions, but each state is on its own to get there.

The Oregon nonprofit Classroom Law Project, which administers the program statewide, raised money to keep things alive locally.

Barbara Rost, the Classroom Law Project’s program director, says the point of Con Team is to teach students about government and their roles as citizens. “The Constitution is just a subject they’re supposed to study for school,” she says. “By the end of Con Team, the Constitution is something they own.”

Grant’s team, comprised entirely of seniors, is divided into six units that focus on different aspects to the Constitution. Some units, like Unit Two, have a heavy historical aspect to their research. Others, like Unit Six, focus on how the Constitution applies to today’s citizens and relies more on current events.

When competing, students face a panel of judges and give prepared and oft-rehearsed statements that respond to their unit’s questions. Then the judges ask follow-up questions that are answered spontaneously.

Emily Olson is a member of Unit Four. She explains that there isn’t necessarily a correct answer to a question, though sometimes the judges are looking for something in particular. “It’s basically how well you say what you’re saying,” she says.

Team members say the experience builds their analytical skills, and teaches them how to work hard and focus. Many say they won’t pursue college or careers relating to the Constitution, but they all feel they’ll be more active citizens because of the experience.

Austin Shaff of Unit Four says the drive to win was a little too much leading up to the state competition. “Everyone was a little too intense about (winning),” he recalls. But he added: “You gotta get a little amped up.”

Shaff says the experience required a “mountain of time.” Con Team, he says, isn’t for everyone. “I’ve had to challenge myself to work as a team,” he says.

Usually, Shaff is reluctant to trust others to produce work of the quality he wants. However, with Con Team, “If you don’t do it as a team, you’re going to lose,” Shaff says.

As the national competition gets underway, take a glimpse at a few of the people who make up Grant’s Con Team experience

The competitor: Halley Steiner

Last summer, Grant senior Halley Steiner spent a month backpacking through the Wind River mountain range in Wyoming with the National Outdoor Leadership School. Carrying a 60-pound pack, Steiner saw bears, hiked 100 miles and summited 13 peaks. “It was basically like ‘Survivor,’” she recalls. “I didn’t want to leave.”

The outdoors has always been a passion for Steiner. “Climbing gets you on a different level,” she says.

But this year, the 18-year-old quit her competitive bouldering team to devote more of her time to Con Team. “Even though I had to put climbing on hold this year, it’s worth it because I’ve learned so much,” she says.

Though she says Con Team takes up “pretty much all my time,” Steiner manages to make room for seven classes at Grant and an expanse of extracurricular activities. “I like to be very busy,” she explains. Social justice is another big theme in her life, and she plans to change a few things in the future.

Steiner was born and raised in Northeast Portland with her older brother, Will, now a sophomore at the University of Oregon. Her parents Paul Steiner and Rose Bonomo separated when she was 10. They remember her as a talkative, empathetic child. “If there was some kid being left out, Halley would go up to them and play with them,” Bonomo recalls.

Steiner was born and raised in Northeast Portland with her older brother, Will, now a sophomore at the University of Oregon. Her parents Paul Steiner and Rose Bonomo separated when she was 10. They remember her as a talkative, empathetic child. “If there was some kid being left out, Halley would go up to them and play with them,” Bonomo recalls.

Her beliefs in equality and social justice were evident from early on. In eighth grade, Steiner became a vegetarian, a lifestyle choice she upholds today. “I was really into animal rights,” she remembers.

She doesn’t remember feeling really passionate about climbing until she went outdoors. “It seemed like I could never go back indoors,” Steiner says. “You get to see untouched places and natural beauty and you get to be with yourself a lot.”

When it comes to social justice, Steiner recognizes her position. “I know I was born lucky into a middle class family,” she says, explaining that there are human rights issues all over the world where others aren’t as lucky as she is. “I’d almost feel guilty if I didn’t do anything about it. I feel a responsibility.”

One aspect of social justice that resonates with Steiner is gender equality. “I’ve been a raging feminist all my life,” she says, adding: “I definitely see women being scared to call themselves feminists. It’s just strange to me that more women aren’t concerned about equal pay and abortion rights.”

Steiner remembers how her mom put her career on hold in order to raise children and doesn’t understand why parenting is still traditionally a female role. She’s frustrated that women still earn less than men. “The facts are clear that we don’t have equality,” she says. “I’m just angry that the laws haven’t changed.”

She also supports gay rights, saying she won’t marry until gay marriage is legalized because the current situation is unfair. “My parents always thought I was too empathetic,” she says. “I would cry when I saw homeless people.”

Now, Steiner plans to make a difference. Her current civic engagement is her involvement with the growing Portland Student Union. “It’s still in the making. We’re trying to get more organized,” she says, adding that she hopes the union continues to grow once this year’s seniors graduate.

Her brother was on the Con Team when he was a senior, something that was problematic for her. “For a couple years, I thought there was no way I’d join,” she says.

But in the end, Steiner joined because she loved to keep up on current events and politics. Now, she says, “I can’t really imagine not being on Con Team.”

Steiner is on Unit Six, which focuses on the future of American democracy and how the Constitution relates to citizens. She estimates they read several hundred pages of material every week in order to be knowledgeable about historical and current events.

“Con Team is exactly what I needed this year,” she says. “I’ve never had to work this hard for any academic activity before. It’s definitely given me more of a sense of direction” for a career.

In the fall, she’ll be attending Western Washington University’s honors program. She plans to study political science, international relations and women’s studies. Steiner is already considering law school, though she’s counting on joining the Peace Corps for a while once she completes her undergraduate degree.

The coach: Andrea Short

Andrea Short remembers her student experience with Con Team as “a lot of blood, sweat and tears.”

A 2004 Grant graduate, Short was a member of the Con Team that placed third nationally. After graduating college, Short returned to help as a coach. For her, it was like completing the circle. “I find it really rewarding,” she says, explaining it’s important to her to give back.

Born and raised in Northeast Portland, Short, 27, was always intrigued by history. She remembers her favorite part of family trips was visiting historical monuments and museums. Interested in genealogy, she also recalls a project in elementary school about where students’ families came from.

She dabbled in other interests like recreational soccer and photography while attending Grant but says she wasn’t particularly skilled at them. Con Team, however, was a different experience. “It was a lot less competitive to get on the team back then,” Short says, saying she’d heard about it through some friends. “I wasn’t exactly sure what it was.”

When her team won state and went to nationals in 2004, Short remembers, “it was exciting, stressful, and a lot of work.” She felt it was great “to have it sort of culminate at the end of the year.”

While in Washington, D.C. for the competition, she got a phone call from George Washington University saying she’d been accepted into the honors program. Everything in her senior year was coming together.

While in Washington, D.C. for the competition, she got a phone call from George Washington University saying she’d been accepted into the honors program. Everything in her senior year was coming together.

The experience solidified her interest in history and government. After graduating from Grant, Short planned to study political science at George Washington. She liked some of the classes she took. She finally declared her major at the last minute in her junior year and graduated with a degree in U.S. history.

Short thought about going to law school to become an attorney, but she realized she was more interested in the academia of law.

After graduating, Short moved back to Portland. But she couldn’t stay in one place for long. She spent four months living in a van in New Zealand with a friend. “Traveling is at the same time challenging and eye-opening,” she says.

When she returned, Short became involved with Catholic Charities, a network of social service organizations that help immigrants. She visited and helped immigrant families study for the U.S. citizenship test. “I would get involved with their kids and parent-teacher conferencing and help the kids with their homework,” she explains.

She remembers working with one man for months; he failed the test twice before passing the third time. Short then helped him read an election ballot so he could vote for the first time. “It was pretty moving” seeing his excitement, she says.

But Short wanted to do more, feeling restless with the job she held at the time in a restaurant. When the 2009-10 school year arrived, Short found herself back in it as a coach.

“I didn’t think I’d actually be a full-time coach,” she says now. “I really was searching for something that would be more fulfilling than the job I was working in.”

Even today, in her third year of coaching, Short doesn’t always feel qualified to coach. The only coach who isn’t an attorney, sometimes she feels like she’s only a step ahead of the kids in her unit, while other times she feels a step behind. “It’s still a learning process for me,” she explains. “I still get a lot out of it.”

Today, she works as a legislative assistant to Democratic state Senator Jackie Dingfelder.

If you ask Short, she’ll tell you that Con Team is a great experience for everyone: students, coaches and the community. “The critical thinking, the writing and the public speaking you learn are invaluable,” she explains.

Her goal as coach is to be approachable for the students. “I try to be closer to their peer rather than an authority figure,” she says. As for the national competition, Short says, “As a coach, it’s really exciting to see everything coming together for the kids.”

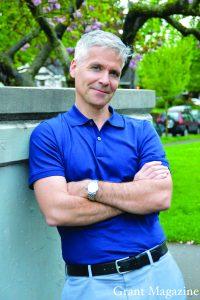

The teacher: David Lickey

If you ask David Lickey what he contributes to Grant’s Constitution Team, he’ll say: “I show up and unlock the door.”

A Grant social studies teacher, Lickey teaches the U.S. Government and Economic Seminar class for the Con Team students, but he claims to be merely an administrator. “I make sure the kids are all there and ready to go. And when things are not there or not ready to go, they talk to me and I make that happen,” he explains.

But the truth is that Lickey does much more.

“This program can’t work without a teacher that cares about it,” says judge and Unit Three coach Henry Breithaupt. “We rely on the teacher, Mr. Lickey.”

Lickey, 46, spends a lot of time on the program. In his fifth year, he works hard to balance the huge commitment with his other teaching responsibilities and a family with three young children.

In his other classes, Lickey, who has taught at Grant since 1993, brings his lifelong love for history to the students. He believes history classes play an important role in preparing students for citizenship. Con Team especially, he says, is “a social education opportunity that is second to none.”

Lickey remembers his own high school education as a successful system for his interests in history. He attended South Eugene High School from 1980 to 1984, which he says was toward the end of a “hippie era of self-actualization.” During his four years there, Lickey took three history classes in each of the three terms per school year. “I majored in history in high school,” he says today.

Lickey remembers his own high school education as a successful system for his interests in history. He attended South Eugene High School from 1980 to 1984, which he says was toward the end of a “hippie era of self-actualization.” During his four years there, Lickey took three history classes in each of the three terms per school year. “I majored in history in high school,” he says today.

His siblings were good students and attended top universities, but Lickey says he was a more average student and didn’t want to compete with them. “I was not much of a high school student,” he recalls. “I said I was going to go into the Army and drive a tank. That way, I wouldn’t have to feel I was a failure in relation to my step brother and sister, who were on a completely different page.”

After graduation, Lickey tried to sign up for the Army. But it wouldn’t take him, saying he had chronic asthma from smoking too much. All summer, Lickey tried to find a way to get into the Army, even calling his congressman to ask for a waiver. But as the summer drew to a close and he still wasn’t accepted, Lickey realized he needed to plan a different future. He would have to go to college.

Lickey hadn’t anticipated attending a university straight out of high school, so he hadn’t taken the SAT or applied anywhere. His mom was working at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio, so Lickey decided to go there. He registered through the Department of Continuing Education, meant for adults rather than recent high school graduates. He was able to apply without providing his academic record or an SAT score. Lickey was essentially a regular freshman at the university, but he got in “through the back door.”

Later, he transferred to the University of Oregon and graduated with a major in history. But Lickey hadn’t given a lot of thought to a future career, and he says even in college he didn’t want to work too hard. “I was always interested in the things the professors had to teach,” he explains. “I approached college like a philosopher.”

Moving to Seattle after graduating, Lickey found himself underemployed at a law firm. He hated the job because he felt he had no power or real responsibility. Lickey moved back to Eugene, hoping for something better.

One day, he was driving his motorcycle around and came across the Oregon National Guard armory. He stopped by to check it out. When recruiters asked if he’d ever applied to the military before, he said no. This was 1989, before the Army began keeping computerized records, so they didn’t find out about his previous application. Five weeks later, he was on a plane to Fort Benning in Georgia for an Army infantry training school.

In basic training, Lickey found himself wondering: “What am I doing here? I’m not an aggressive person, not ever going to be a good soldier.”

He doesn’t regret it. The four months at Fort Benning “gave me a real opportunity,” he says today. “I grew up a lot.”

When he began thinking about what to do next, Lickey wrote his mom a letter from boot camp asking for information on “teacher colleges.” After leaving boot camp, he volunteered at a school in Eugene for a year because he had to have experience working with youth in order to attend a college for his teaching license.

Lickey got his teaching license in 1992 from Western Oregon State University and began substitute teaching in Portland. Then, in the middle of the school year he took a long-term substitute job at George Middle School. He taught students who were so misbehaved that they’d gotten their teacher to quit mid-year. Lickey remembers his excitement on his first day and his hope for the upcoming months, only to find a tack glued on his chair within the first few minutes. But Lickey didn’t give up and continued to do his best “even though my best was not enough.”

He made a good impression and a staff member recommended him for a social studies position at Grant High School. He was accepted for the job and began teaching in the fall of 1993. “I got this job. I consider that to have been the greatest good fortune of my lifetime,” Lickey says.

As the 2008-09 school year approached, the Grant Con Team found itself lacking a teacher. Lickey remembers when the topic came up during a meeting. “Everybody in the department looked at their feet and my heart started going bum-bum-bum-bum,” he recalls. “So I said, ‘Okay, goddammit, I’ll do it.’”

The Con Team class is different from his other classes. Though in the beginning of the year the class looks similar to any other history class with its textbooks, lectures and class discussions, by spring term the structure is greatly changed. These past few months, his students came into the classroom, wrote down what their unit needed to do and got to work. Because the students had so much work to do, “When I tell them to update their logs and get to work, they get to work,” Lickey explains. “If I can help them with something, then I will. Sometimes I can, sometimes I can’t.”

Lickey believes the students get the real expertise from the volunteer coaches. Con Team is “possible because the 12 adults are willing to come in here and do this for the kids in their neighborhood,” says Lickey.

Teaching Con Team has made him a better teacher, he says. “Constitution Team as a teacher taught me how to stop teaching to make room for students to learn,” he says.

In his history classes at Grant, Lickey used to give lectures to his students. Today, he writes an outline on the board and starts asking his students questions. “Learning happens in the mind of the learner. It’s not something that is put in your head by the skill or the will of the teacher, and that’s something that the Constitution Team helped me to see,” says Lickey.

January’s victory has made the ride this year that much better. “The thrill of winning the state competition and beating our rival, Lincoln, that is sweet. There’s nothing better,” says Lickey.

Despite what he says, Lickey’s contributions aren’t small, team members and coaches say. “It’s hard because I have a family with three small children and a wife who works, whose job is more important than mine financially and has pretty big obligations,” Lickey says. He won’t be able to teach Con Team forever, he explains. In fact, this year will be Lickey’s last.

Con Team hasn’t been a good fit for Lickey’s interests. “I’m a history person,” Lickey says by way of explanation. For Grant’s Con Team to be the best in the nation, it needs a teacher who can teach government and political science, and he says, “I’m not that guy.” Grant social studies teacher Jeremy Reinholt will take over next year, and Lickey says Reinholt’s passions match up better with Con Team as a whole. Lickey says maybe he’ll be a coach.

When he’s not teaching or helping out with Con Team, Lickey shuttles his kids around to their various practices and clubs. He also enjoys cooking and makes most of the family meals. In his free time, Lickey likes to go to Pete’s Coffee on Broadway to make conversation with strangers, who become his friends over time.

Lickey says his interests are a mile wide and an inch deep, but unfortunately he isn’t able to enjoy them very often. For example, he’s always had a fascination for motorcycles. “But do I live out these biker fantasies and ride my motorcycle and get involved in a motorcycle club?” he asks. The answer is no: Lickey’s free time is largely spent on Con Team.

“To culminate with this trip to Washington and having that be the way that the students end their high school career… it’s just what you’d want for the most high achieving, highly accomplished high school students,” he says.