“Carlos Ortiz” remembers five years ago sitting in his seventh-grade math class at Vernon School in Northeast Portland. Suddenly, a teacher who had looked after him since he started at the school rushed in and pulled Ortiz aside. “Stay with me,” she told him.

Earlier, two immigration officials had walked into the main office and asked to see a student before taking her away. The teacher told Ortiz what happened. He immediately wondered if the officials would still be outside when his parents came to pick him up from school. After the incident, Ortiz stayed home for a week.

“Most people don’t understand how quickly I could just disappear,” says Ortiz, now a Grant High School senior whose real name is being withheld because he fears his family might get deported. The girl from Vernon “didn’t have a chance to say good-bye to anyone, she was just gone,” he recalls.

Many first and second-generation immigrants walk the halls of Grant every day. While most have some form of legal documentation, a few are on the outskirts – longtime residents without the right paperwork. Their families are all tossed into a completely different world, while simultaneously forced to cope with settling into a new country, home and workplace.

Language barriers, fear and the law limit opportunities and a brush with authorities weighs heavily in the background. During a period of active local and national conversation about immigration policy, Grant students are forced to make sacrifices.

Orlin Dubon-Caballero, a 19-year-old senior at Grant, remembers his middle school friends talking to him about what lay ahead when he was preparing to leave Honduras for the United States. Money, they told him, drifts through the wind and lies flat on the sidewalk in America. All you have to do is pick it up, they said.

For Saimon Asghedom, 17, of Eritrea, the process took years. In 2009, his mother left Asghedom, his sister and father and settled in Portland. She opened a small market in North Portland on Dekum Street. When Saimon was 14, he and his family moved to a small settlement in Uganda to escape political oppression and violence in their homeland.

After two years, he moved to Kenya because there was better access to the American embassy. Finally, after years of paperwork and insecurity, they received approval to join his mother. “I can say I saw the world,” Saimon says today. “My country is very undemocratic but life here is not so bad.”

The transition can be difficult, says Britt Conroy, a specialist for education and support services for the Ecumenical Ministries of Oregon’s Sponsors Organized to Assist Refugees program. Conroy works with three Grant students, whom he helps understand the school system and how to connect with the necessary services.

Last year, the federal government approved the first part of the Dream Act, called the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, enabling those who came to the United States illegally as children to begin the process toward citizenship with temporary residency. For some Grant students, this offered a tremendous opportunity.

We found three Grant students who were born abroad and have each endured their fare share of struggle. Here are their stories.

Margaret Amoo

Margaret Amoo remembers how the words stung.

“You look like ‘Coming to America,’” a classmate said to her in front of her entire Algebra class last year. The person was referring to the comedy film starring Eddie Murphy as an African prince trying to manage life in New York City.

Wearing her traditional Ghanaian orange “shada” pants, Amoo had had enough. The girl always turned to her friends and made fun of Amoo, but this was the first time she had the courage to say something to her face.

Wearing her traditional Ghanaian orange “shada” pants, Amoo had had enough. The girl always turned to her friends and made fun of Amoo, but this was the first time she had the courage to say something to her face.

A Ghanaian native who hopes to become a U.S. citizen, Amoo said she wanted to express her cultural roots openly when she arrived in 2011, but it hasn’t been easy. “I tried to ignore it because in my culture we are taught not to argue, not to fight, but to respect,” Amoo says. “But there are a lot of people that are mean here.”

Amoo, 19, moved here to be with her father, leaving her mother and sister behind. While a continent and an ocean separate her from her hometown, she maintains her love of Ghanaian dance, food and people. “In America, they have a different way of doing things,” Amoo says, “and most people don’t know anything about my culture.”

Amoo was born in Accra, the largest city in Ghana and its capital. When her mom was pregnant with her, the parents split. Her mom remarried and her dad left for the United States. Amoo was raised by her mom and stepfather.

She recalls the day Ghana’s military government gave way to the first democratically elected president. Amoo was standing on the side of the road with her sister when a driver lost control of a vehicle and ran over her leg. After five surgeries, multiple broken bones and a year in the hospital, Amoo was released. Nothing but the scars remain. “Any time I see the scar, I feel like crying,” she says.

A year before Amoo came to the U.S., her birth father Edmund Amoo came to Ghana to visit her. It was the first time they had ever seen each other. “I didn’t know my dad. I never talked to him. I didn’t even know he was my dad,” she says.

When Edmund Amoo moved to the U.S. for good 20 years ago, he took a job as a fish processor for American Seafoods. In 2010, he brought her back to America.

Today, Amoo maintains aspects of her cultural roots. She danced as a young girl, training with a group for years and even performed in national events. This year, she participated in the Grant talent show. “In Ghana, we dance with a passion,” Amoo says. “We talk through our dance. We don’t just dance. We dance with happiness and all our hearts.”

She also holds onto her community’s language of Ga, the spicy food and the clothing. Once a week, usually on Fridays she says, she tries to wear African clothes to school.

One of the greatest differences Amoo notices between America and Ghana is the concept of family and home. “In Ghana, my parents can have their own house that I can go to anytime and sleep, pay no bills, pay no rent, pay no electricity,” Amoo says.

At school, many foreign-born Grant students like Amoo seek out the English Language Development classroom as a sanctuary of respect and friendship. “I have friends, but we are all from different countries,” Amoo says. “We all want to make friends, so it’s not as hard.”

Living here has some advantages, she says. “I like it here because there’s a lot of freedom and opportunity.” In the U.S., she argues, “when you’re 18, you’re grown up, you can do whatever you choose.”

Amoo expects to graduate at the end of the year. Her dad wants her to join the military, but if she doesn’t get in she will attend Portland State University with the hope of studying business administration.

“Carlos Ortiz”

In 2010, Carlos Ortiz’s club soccer team was set to travel to San Diego for a college showcase tournament.

Ortiz stood quietly at a team meeting when his coach asked his players if there was anybody who wouldn’t be able to make it. “My parents were super fearful about me going,” Ortiz says. San Diego, he says, is regarded by many in the Latino community as a city where people often get deported.

The coach had already purchased a ticket for him and so Ortiz had to tell him the truth: His parents were terrified. The coach called them and told them not to worry. They let him go as long as he followed these rules: don’t draw attention to yourself, especially in the airport. Behave yourself. Always be on alert.

“It’s always in the back of your mind, constant fear, constant lying, constant things you have to cover up,” says Ortiz, now 17. “But there are a few people here and there that you have to open up to over time.”

The decision the family made to get to the U.S. by any means in 1997 produced a lifelong source of stress, but it wasn’t something he could talk to just anybody about. Seemingly a normal kid, Ortiz says he has lived “almost a double life,” managing social and academic situations at school while hiding his secret – he wasn’t in the U.S. legally. When the opportunity arose to change that this year, he couldn’t pass it up despite his family’s worries.

His parents went to school together in kindergarten in the small town of Ayutla de los Libres, near the city of Acapulco. His dad was a hotshot soccer player and would frequently play with his future wife’s brothers.

The first time he talked to her was at a dance. Confident and handsome, he asked her to dance and she replied: “a la otra” or “next time.” Eventually, they started dating in high school. In 1994, when they were 23, they married.

The family decided the best available opportunity to escape and gain a steady income was to get to the United States. The dad traveled with a group of friends to the border, leaving his wife and son at home. He paid a “coyote” smuggler to smuggle him across the border and quickly found his way to Los Angeles. He picked up two jobs, prepping food at one restaurant and bussing tables at another.

A year and half later, Ortiz and his mom traveled to the border to reunite with his dad. On their third attempt in four months, the dad finally landed an immigration attendant willing to grant them their temporary tourist visas.

In 1999, they moved to Oregon because it seemed the laws governing immigration in California were much more strict. Portland, they found, seemed to offer less of a risk.

“When we first got to Portland, I wouldn’t see my dad at all,” he remembers. He was working long hours.

As college approached for Ortiz, he says, “I just thought I wasn’t going to go.” His lack of a Social Security number stood in the way. “I didn’t see it as an option,” he says.

When Ortiz was in sixth grade, one of his cousins was admitted into the University of San Francisco with a generous financial aid package. After two months in school, they asked her for her proof of legal residence. When she couldn’t provide it, they kicked her out. “Knowing something like that could happen made it even worse,” Ortiz says.

But when the Dream Act was passed, Ortiz gained hope. Two months later, Ortiz decided it made sense to participate in the process, but his parents remained skeptical. “So you apply, let’s say they don’t accept you. Does that mean you get deported?” his mother wondered.

After talking to friends and relatives who had gone through the process first hand and consulting with the lawyer about every possible outcome, “we were 100 percent sure nothing was going to go wrong,” says Ortiz.

Ortiz filled out the application and provided all the necessary documents: his birth certificate, school record and transcript. Five months and $1,500 dollars later, his Social Security card and employment authorization card arrived, giving him legal status as a temporary resident.

Ortiz didn’t apply to college until he received his legal documentation. “After, I could apply with confidence,” he says. “At this point, I think it’s very likely that my parents will eventually become citizens themselves.”

Orlin Dubon-Caballero

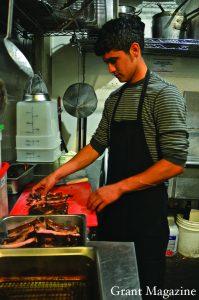

It’s 11 p.m. on a Saturday night and senior Orlin Dubon-Caballero, 19, is finishing up the last of the dishes and helping to finally close up the kitchen at Eat!, the oyster bar on North Williams Avenue where he works more than 30 hours a week.

He has been working since the afternoon. His hands feel worn and his eyes are barely open. Checking his bank account on his phone, he ensures he has enough money to pay the $300 in rent at the end of the month. “Everybody thinks it’s so easy to become rich here. It’s not true,” says Dubon-Caballero. “I know because I have been working.”

Orlin Dubon-Caballero’s mother and stepdad’s longtime effort to get him here legally from Honduras keeps him from going back, but now he is living on his own. After four years in the U.S., Dubon-Caballero still struggles to connect with new people his own age and keep his head above water.

Orlin Dubon-Caballero’s mother and stepdad’s longtime effort to get him here legally from Honduras keeps him from going back, but now he is living on his own. After four years in the U.S., Dubon-Caballero still struggles to connect with new people his own age and keep his head above water.

“When I left my mom’s house, I told her I wasn’t going to need her help anymore. I wanted to handle everything on my own,” Dubon-Caballero says.

When Dubon-Caballero’s mother was pregnant with him in the rural Honduran village of San Marcos, his father disappeared. One year later, his mother left for America, leaving Dubon-Caballero with his grandparents. She traveled to Mexico, using $5,000 from her parents to pay a “coyote” smuggler to help her across the border. Once on U.S. soil, she came straight to Portland. She was hired at McDonalds and has been working there for 15 years.

Dubon-Caballero remembers calling his mother, Jesus Caballero, from Honduras about once a month. Because she had entered the U.S. illegally, she didn’t come home. In 2007, Jesus Caballero remarried an American in Portland. They immediately worked to get Orlin and his two older brothers to the United States, legally. In 2010, when Dubon-Caballero was 16, his mother returned to Honduras for the first time since he was one.

“I had only seen her in pictures,” Dubon-Caballero says. “But I remembered her face.”

His mom asked a relative if this boy was her son. “I thought I wasn’t really talking to my real mom that day,” he recalls. “It felt strange, but I was so happy to meet her.”

Dubon-Caballero arrived at Grant that year as a freshman with no English experience. “I never wanted to leave Honduras,” he says, but once the paperwork was filed there was no turning back.

“For the first two months here, I was arguing with my mom that I didn’t want to be here,” he recalls.

Though Dubon-Caballero is still interested in returning to Honduras, he only has permission to be gone for six months. “She worked too many years to get us here,” he says. “I don’t want to lose all the work she did for us.”

Six months ago, Dubon-Caballero moved out on own. He lives with friends he knew in Honduras. He pays for his rent, food, transportation and clothes. He takes an ELD class and has finished most of his high school credits by taking courses at night school and summer school.

When it comes to budgeting, Dubon-Caballero says bluntly: “I don’t spend my money.”

He will graduate at the end of the year and plans to start at Portland Community College before eventually transferring to a four-year-college to become an electrician. “It’s not as stressful anymore. Now I know some English. I just have to keep working,” Dubon-Caballero says.