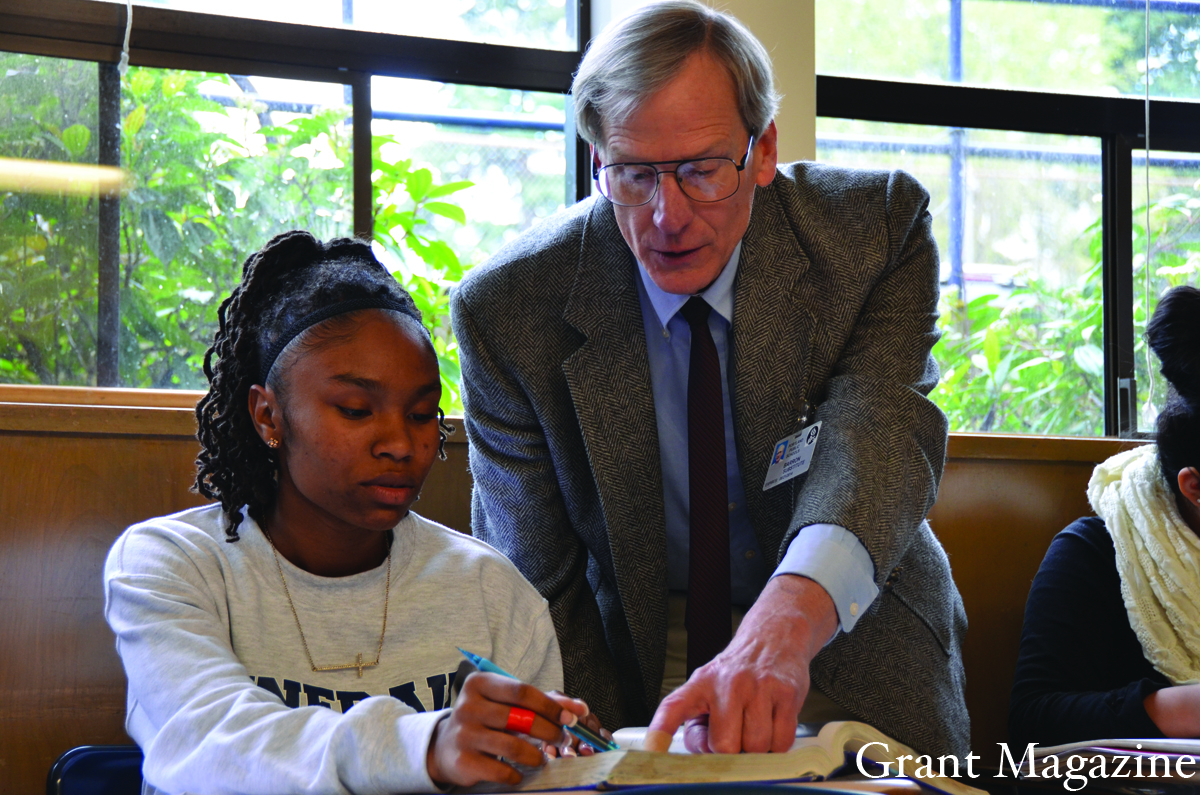

Sitting behind Grant social studies teacher Don Gavitte’s desk for the day, the man known only as Barron patiently waits as students file in the door and take their seats for the U.S. history class. Some begin chatting, while others pull out their work and start reviewing for a quiz.

He quietly observes, getting a sense of the general classroom mood. When the bell rings, he stands, smoothes his signature herringbone sports jacket and straightens his wire-rimmed glasses. He introduces himself for those who don’t know him, using only one name. He legally removed the rest years ago.

Barron has been a substitute for almost 35 years, and unlike most subs, he wouldn’t have it any other way. Rather than taking on a full-time teaching position, Barron embraces the variety and immediacy of subbing. He is commonly referred to as a “permanent sub,” having worked almost exclusively at Grant for the past 20 years.

Teachers battle to request him, as he is known for being extremely dependable. His unique character, curious way with words and mysterious life outside school have left students and staff pondering for many years. “A lot of people are afraid of what other people think, while he glows in the uniqueness of his lifestyle,” says John Mears, a Grant special education teacher who has worked closely with Barron for more than 20 years.

Mears appreciates Barron’s engaging persona. “He doesn’t throw [his uniqueness] at you, he includes you in it,” Mears says.

He compares Barron to a beatnik or a hippie from the early 1960s living an average, middle-class life today. He plays his role as a substitute, wearing what he calls the “traditional teacher’s costume” to show respect for his job and his students, and to blend in as best as possible. But beyond his clothing and riddling words, Barron is a fun-loving, passionate activist who is extremely intuitive.

Barron was born on July 20, 1947, in Madras, a small town in the deserts of Eastern Oregon. His father, Howard, was a high school English and journalism teacher. His mother, Dorothy, remained at home to take care of the five children. Barron recalls the comfort of coming home to his mother along with his three sisters and one older brother. “I felt really secure at home,” he says, “We all got along extremely well.”

Barron compares his family to that of the Cleavers in the old TV show “Leave it to Beaver.” They strived for a conflict-free home, and if they ever strayed from that, they did whatever it took to sort things out. Both of his parents were always extremely accepting and supportive, and encouraged all of their children to do what they felt was right. He recalls going on many family outings, such as making the short trip to the Cove Palisades at Lake Billy Chinook. The parents turned the children loose to climb the huge rimrocks of the canyon to the top where they would meet them.

During a time where racial prejudice was common, especially in such a small town, Howard and Dorothy did everything they could to steer clear of such intolerance. Dorothy even subscribed to “Ebony” magazine – a publication geared toward African Americans – to show the family that “not everyone was white.” They emphasized acceptance of other’s beliefs that differed from theirs, and to this day, Barron abides by these values.

In his free time, Barron enjoyed being alone, hiking and biking through the desert. He and his friends would get in cars and “drag” Main Street. Outside of town, illegal races were common, although Barron never had a car that he raced.

In high school, Barron was more of a social butterfly than a scholar. The school was a place for him to interact with his friends, and he had very little interest in his schoolwork. Although he never skipped a class, he often joked around and disturbed his classmates. He did the bare minimum. He wasn’t into sports because by the time the school day was over, he was more than ready to leave.

“After being told what to do all day by the teachers, I wasn’t going to voluntarily go back to school and get told what to do by the coaches,” he says.

He did take an interest in photography, looking up to an upperclassman who was the school’s newspaper photographer. The student eventually passed on his skills to Barron so he could take over. Barron arranged for a darkroom to be installed in his school and he started spending the majority of his time processing his photos there. As the only photographer in the school, it was like having his own darkroom.

Before he could process his own photos, he would take his roll of film to the local drugstore, which would ship them to Portland for processing. He loved being able to create something that could be shared with others, and his work ran in the yearbook, too.

He turned 18 in the summer of 1965 and a few months later began college as a freshman at Pacific University in Forest Grove. He chose journalism as a major, hoping there would be an opportunity to do some photojournalism. He quickly discovered there wasn’t, and as a freshman, he was not eligible to be on the school newspaper staff.

The school threw together a darkroom for him, but it was inadequate. In high school, the most writing he had done was creating photo captions, which he found to be quite difficult. The assignments in his journalism classes were much harder work than he was prepared for. His social ways carried over into college, where he frequently partied and received poor grades in return. He coasted through for two years, and by the fall of 1967, he had flunked out of college and was working at a farm equipment factory.

By March 1968, at age 21, Barron received a letter informing him that he had been drafted. “I disliked everything about the military; it was enduring the constant insults,” he says now. “It’s the opposite of what I grew up with where instead of you could do what you felt was right, you could only do what you were ordered to do. That just didn’t seem right.”

Having more experience than those who went in fresh out of high school, Barron was able to maintain a better sense of himself and not be completely broken down and rebuilt into the “machine” that he believes the military wanted. Having never been a fan of mindless obedience, he tolerated it because he had to, swearing he would never get himself into that kind of situation ever again.

When Barron was drafted, he was meant to be in for six years total. During his active service, Barron was trained in artillery and was a payroll clerk for most of his time. Toward the end of his first two active years, Barron found a loophole. “I discovered that if you fill out the right paperwork and prove that it’s in the best interest of the country for you to leave early, then they’ll let you out early,” he says. “So, I did all the paperwork and got out early.”

He claimed that he would re-attend college upon his discharge from the service. In the winter of 1969 Barron returned home at age 23. He enrolled at Central Oregon Community College in Bend, taking a three-hour night class to fulfill the requirements, fearful of being redrafted if he didn’t. By the following fall, he enrolled at the Oregon College of Education, now known as Western Oregon University. This time was different. He came ready to work. “When I went back to college the second time, I learned my lesson,” Barron says now, “I treated it as a business.”

He claimed that he would re-attend college upon his discharge from the service. In the winter of 1969 Barron returned home at age 23. He enrolled at Central Oregon Community College in Bend, taking a three-hour night class to fulfill the requirements, fearful of being redrafted if he didn’t. By the following fall, he enrolled at the Oregon College of Education, now known as Western Oregon University. This time was different. He came ready to work. “When I went back to college the second time, I learned my lesson,” Barron says now, “I treated it as a business.”

He never skipped a class and always kept up on his homework. As it was a much larger school than Pacific University, Barron didn’t get into the social scene. He did, however, meet two couples: Denny and Deb Anderson, and Marv and Rindy Ross, who have since become lifelong friends.

“He was so unique; he didn’t fit into any mold.” Denny Anderson says, “He could blend in anywhere observing. He was kind of like a visitor from another dimension, searching for intelligent life on Earth.”

Denny Anderson describes them as “hippie musicians,” while Barron was “on his own wavelength.” He remembers Barron spending a lot of time in his backyard, enjoying nature. Barron valued peace, quiet and privacy, much like he does now.

The rest of us eventually came to deeply value those same things, but it took awhile for us to get there,” Denny Anderson recalls. “Now that I think about it, he was a huge influence on all of us.”

Barron says he has always felt as if he was from a different planet, and he goes about ours as a visitor and sociologist. He began questioning everything, whether it was religion, society, government or relationships. “The idea that something was right because it was the way it was always done was thrown out completely,” he says now. “It had to be right because it was right.”

After graduating in 1973, Barron began working as a counselor in a residential treatment center in Hood River. The residents in the home were wards of the state. They had been to correctional juvenile centers and were ready to integrate back into society, but didn’t have homes. Barron recalls holding group meetings to help the kids better themselves and their lives. Although he enjoyed it, Barron did not see eye-to-eye with the pair of directors. “The kids had their heads together better than some of the people I had to work with.” He says.

After a year, Barron moved on. All he had was his suitcase he had brought with him a year earlier. So he got a backpack and set out on his first hitchhiking journey in the summer of 1974. “It’s really unfortunate that people are so fearful today that we don’t hitchhike,” Barron says, “It’s really a great way to meet people and it’s pretty cheap travel.”

He traveled into the South, up the East Coast and even into Canada. Locals were always happy to show him around. Some would offer him the chance to pitch his tent in their backyard and even use their shower. The next morning, he would be on the move again.

Barron kept in touch with his family as best as he could. It was very important to him to remain close with them, especially when he made a big decision upon his return. Barron dropped his first and last name in 1975, leaving him with his middle name, which he had gone by for most of his life. It was something he had thought of doing, and at the time, “it just felt right.” He never used his first name and wasn’t going to pass it on as his father did to him, and he felt his last name was too small of a group to identify with. Barron explains that he is part of the whole human family, not just part of the “Johnson” or “Smith” family. He emphasizes that Barron is not a title, but a name. (He points out that he is opposed to hierarchy and “Baron” with one “r” is a title of a Knight, a Duke, or an Earl.)

He moved into a farmhouse with his friends from college, the Andersons and Rosses, who were all full-time teachers while he began subbing. He immediately liked it. The transition from the residential treatment center was natural and easy. He was able to pick up on the students who needed extra attention, and approached them first rather than waiting for them to “demand” his help.

Barron never thought of subbing in terms of a career. “It seemed like a great thing to do, and as long as it’s great, I’ll continue doing it,” he says. “Now, 35 years later, I’m still doing it.”

He traveled to Washington, D.C., for the United States Bicentennial in 1976. There was a rally on the Capitol’s steps that overlooked a huge gathering in the park below. He listened as Jane Fonda spoke about America’s occupation in Vietnam, which had ended three years earlier.

Barron carried a journal, jotting down his day-to-day sightings and experiences. “So much happens in a day and you know you’re not gonna remember it all, so I would write down as much as I could remember from the day,” he recalls.

He returned to Bend in the fall broke and in need of fast cash. He put his degree in Secondary Education back to work and continued substitute teaching. In his time off, he moved pianos and organs. For four years, he subbed in Bend, until he met a woman at a party and began traveling with her and her six-year-old daughter. They went to New Mexico, then California, and in 1980, they split. Four years later, he moved to Portland.

In 1984, he bought the house he lives in now and became a full-time substitute. He began writing advertorials for an industrial company for trade journals on the side, where he finally got to dabble in photojournalism. Subbing was perfect because when he needed to travel for his advertorial job, he could clear his calendar and go. Barron had always enjoyed desktop publishing, and through his side job, he was able to get his dream computer – an original Macintosh, where he could publish his newsletters and magazines.

In 1987, he began putting out newsletters for his made-up religion: the Universal Church of Fun, a universal faith that doesn’t replace anyone’s religion. It just helps them find the fun. He figured: People either already have their own religion or they don’t really want any, so there’s no sense in adding more. But everybody likes fun.

“Just having fun can be self serving, but when you start making fun for others to have, then the fun spreads, and eventually you just become one with fun,” Barron says.

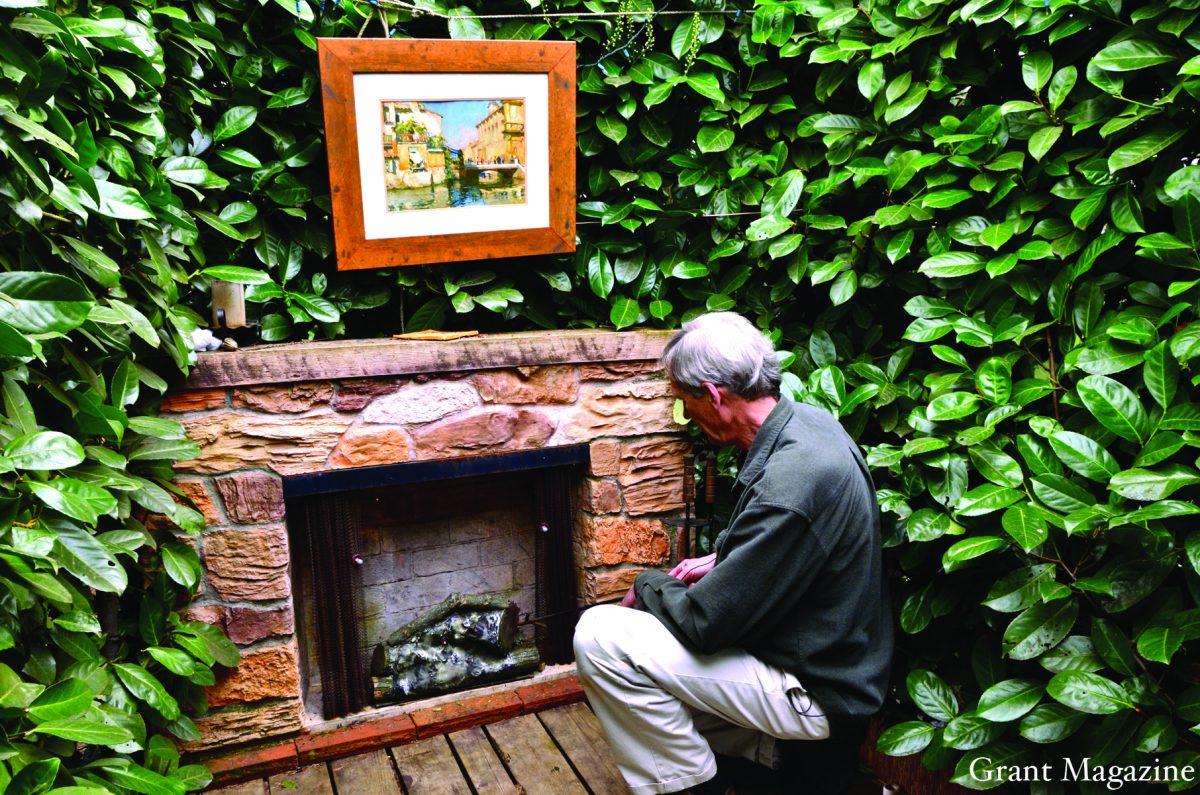

Denny Anderson remembers the day that he and Barron found an article in an old Modern Mechanics magazine from August 1932 about an entomologist with a peculiar hobby: recreational tunneling. Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. had a series of tunnels under his house. They both found it fascinating, and Denny eventually wrote a short story about it. Barron took it a step further. He has an elaborate tunnel in his backyard, which has since been deemed the “World Famous Woodstock Mystery Hole.” His backyard, which he refers to as a “big, bottomless toy box,” has grass that is bright and always freshly trimmed. It’s perfect for his favorite summertime hobby: “Zombie” croquet. At the back of his property, a neatly pruned hedge stands tall and full. It’s completely hollowed out with a ladder leading up to what he calls the “hedge walk.” At the end, he slips on his special gloves and slides down a pole, thumping against the ground.

The hole quickly became a hot tourist attraction. Barron began tours shortly after moving to Portland, ending them 10 years ago. Now, if someone wants a tour, they must contact him privately and arrange a time. He has never charged anyone for a tour.

Barron spent most of his substitute teaching time in North Clackamas. He says taking those jobs made it easier to get subbing gigs in Portland.

Grant Principal Vivian Orlen remembers passing Barron in the halls frequently during her first few months at school. But she didn’t recognize him as a staff member. Now, she can tell that he clearly “builds good rapport with students and staff.”

“He is a complete cult of personality,” she says.

Barron subbed at a lot of different schools in Portland at first, but once he established a reputation, he began subbing almost exclusively at Grant. “It makes me appreciate Grant more,” he says. Now, 80 percent of his jobs are at Grant.

Barron subbed at a lot of different schools in Portland at first, but once he established a reputation, he began subbing almost exclusively at Grant. “It makes me appreciate Grant more,” he says. Now, 80 percent of his jobs are at Grant.

Angie Payne, Orlen’s secretary, refers to Barron as her favorite substitute. She has found him to be extremely dependable over the years, and has never once received a complaint about him from anyone. Often times when Barron is subbing and has a free period, he will pop into Payne’s office and offer to help her with anything she needs. He offers to fill in if any substitutes don’t show up. “He is always willing to go the extra mile,” she says.

Kelley Lauritzon, another secretary at Grant, describes Barron as a kind spirit. “No matter what environment you throw him into, he always goes into it with ease,” she says.

He embraces the difference between a full time teacher and a substitute – he goes to different schools, has different students and different classes. Subbing has helped him appreciate each person he meets. “We never really know what will happen each day and that goes triple for subbing,” he says. “It helps not just knowing the students but having the students know me. They know by reputation that it’s probably going to be a positive experience.”

When asked if he plans to retire, Barron says he is already semi-retired, but doesn’t plan to. “I wouldn’t mind continuing to sub until I can’t remember what room number I’m looking for,” he says.