Freshman Yaislenis Estrada remembers coming to Grant and being somewhat overwhelmed. As her English teacher stood at the front of the class lecturing, she slowly began feeling confused.

Estrada would revisit the teacher after class or ask another student for help, but still struggled. Estrada is from Cuba and is trying to master English as her second language, but it doesn’t always come easy.

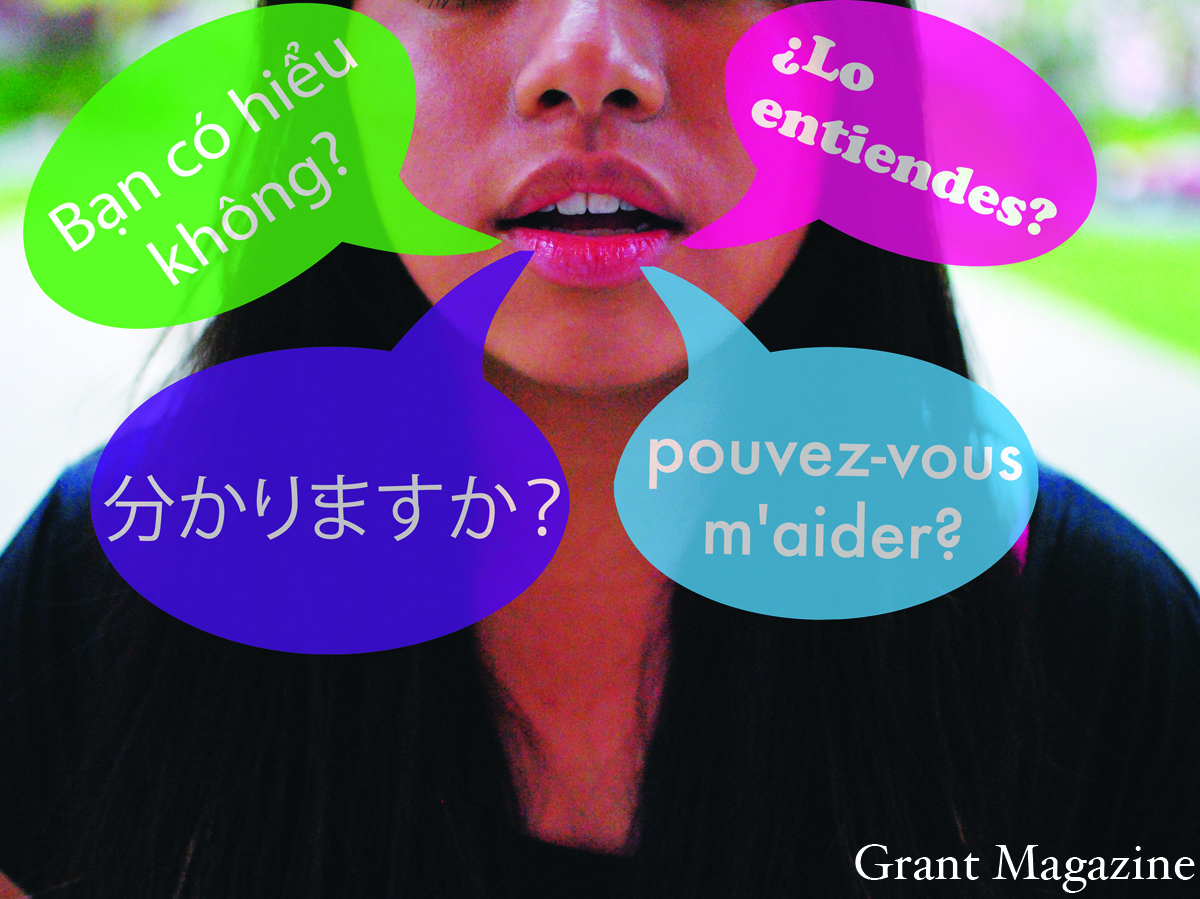

Unfortunately, this is a common occurrence for students at Grant who struggle to adapt to a curriculum taught in an unfamiliar second language. Not only is it frustrating for students, it’s also frustrating for teachers who don’t always have the time or resources to go over a lesson again with a student who does not understand it at all.

The English Language Development program at Grant is the place where these students traditionally can get help with the homework they don’t understand. But this year, Grant teacher Marta Repollet is striving to make it a place that will not only help these students through high school but will also build an English language foundation for their futures.

According the United States Census Bureau, approximately one in five Americans do not speak English as their first language. There are about 4,500 students within the Portland Public School district who are in the English Language Development program (ELD), 16 of whom are students at Grant. Across the state, Portland has the third largest ELD program.

But whether they are a part of the ELD program or not, students who don’t speak English as their first language are at a disadvantage. Not understanding the curriculum, falling behind and not getting the help they need to be successful are just some of the issues these students are facing.

Estrada also says that it can be hard to communicate and socialize with her peers because of the language barrier. Most of the ELD students feel like their closest friends are the other students in the program.

The ELD program’s mission statement declares: “By the end of elementary, middle, and high school, every student will meet or exceed academic standards and will be fully prepared to make productive life decisions.”

But according to statistics from the Oregon Department of Education, fewer than 30 percent of ELD students within the district become proficient in English after five years in the program. In addition, only 49 percent of ELD students in Portland were able to hit the English proficiency test target score in 2012, which is below the expected 57 percent of students.

The statistics show that the ELD program is failing to produce students who leave high school with enough confidence to speak English well. ELD advisor and teacher Repollet is trying to change that.

Repollet has been teaching history at Grant for seven years and has been the instructor for Grant’s ELD program since November 2012. Her attraction to the program stemmed from her childhood experiences as the daughter of parents who emigrated from Argentina to New York. As a child, she herself was an English Language Development student, although she began to learn the language at a much younger age than the students in the ELD program here at Grant. “I feel like I have personal experience that sensitizes me to those students,” says Repollet. “I realized that after I got trained in ELD and looking at the stages that kids go through when they’re learning a new language, that I too went through a similar stage.”

ELD kids often go through periods in which they don’t speak at all, called the “silent period,” and this is often because they aren’t comfortable yet with the English language. “There’s a stigma, a shame thing that’s associated with speaking with an accent, as they perceive it,” says Repollet.

Going through this often makes it even harder for these students to advocate for themselves in class. Because they often can’t understand English well enough to keep up with their classes, it’s easier for ELD kids to find themselves falling behind. “They’re very invested in their classes and they want to do well, and when I see them in ELD class, immediately they want to go over their general ed. material. They want to go over their Chemistry, or they want to go over their English assignment,” explains Repollet. “And what I have to do is kind of put the brakes on that, and say, ‘We first have to learn the language.’”

Having gone through the process of learning English as a second language herself, Repollet understands the amount of patience it takes to help her ELD students when they struggle in school.

Repollet worked with Vice Principal Kristyn Westphal to add a “sheltered” class. The sheltered class is full of only ELD students to provide a comfortable environment for the students to work at a slower pace.

On a recent weekday, the ELD students gathered in Repollet’s eighth period sheltered Modern World History class. While they waited for the bell, they excitedly chattered with one another. The room filled with many languages: little bits of Spanish, little bits of Russian. When the bell rang, Repollet stood up and began her lesson, a PowerPoint on grammar.

The class listened and took notes as she led the class. Hands went up in the air and Repollet took time to slowly explain what was going on. As the lesson drew to a close, students began to pull out their homework. Repollet tried to go over the assignments that the students didn’t understand in their other classes.

It’s common for teachers to have a student help one of their struggling ELD peers. Students who speak English along with a second language can help in translating lectures for students who don’t understand English as well. Repollet says sometimes this strategy is beneficial, but other times it hinders the ELD student because they don’t get the opportunity to practice their English or try and interpret it for themselves.

“A lot of times if there’s students in class that don’t speak English they ask me to help them,” says sophomore Taney Hennick. Hennick is from Mexico and is fluent in both Spanish and English. Most of the time she says she doesn’t mind “because it’s pretty easy and fair.” But it can get in the way of her own learning.

For now, Hennick is fine with helping her peers out but she doesn’t think that is going to be beneficial for anyone long term. “Teachers should know minimal Spanish, or whatever language their students speak,” she says, noting that most teachers don’t understand key phrases.

Repollet says she’s been noticing people see the ELD students as burdened or helpless because they don’t speak English, but both she and Westphal see it the other way around.

“There’s really a focus now on talking about students who are learning another language as emerging bilinguals,” says Westphal. “So really focusing on the fact that they have a skill that most Americans don’t have, being that they speak another language other than English.”

In previous years, Westphal says that the ELD classes were more of a time where students could get their assignments completed rather than becoming familiar with the language. Repollet knows how important the language itself is, not only for the students to complete their assignments but also for their futures.

Repollet emphasizes that it’s not always about getting their Chemistry assignment done or getting their history homework out of the way. It’s about the bigger picture: learning the language. “My goal for the program is to build curriculum that’s going to steadily increase every ELD kid’s language proficiency,” Repollet says.

Ultimately, she says these kids will never be proficient in the English language unless all of the teachers get on board with balancing their general education students’ questions and helping ELD kids understand the content.

But the battle isn’t that simple. It’s true that teachers should help students to their best ability, but taking the time in class to make sure ELD students understand everything is not always realistic. Repollet says communication is important and students need to work hard to be flexible and come back after class. “I’m their advocate. I communicate between the students and their teachers,” she says.

Westphal says she would like to see more sheltered classes in the future so the students can learn at the pace they need and have a teacher who has time to re-explain what’s going on. However, it’s hard to think about adding more sheltered classes when electives are already being taken away due to the lack of financial resources within the district.

Statistics show that ELD programs aren’t doing as well as they probably should, but everyone involved with ELD at Grant feels confident that they will get there. It’s going to take time to get all of the students on the same level, but what ultimately counts is giving the students basic English skills to help them succeed after high school. Both of the two seniors in the program this year are planning on going to college.

It will take time, cooperation, and more funding to bring the ELD programs across the state to the next level, but Repollet feels confident that it’s possible.

For students like freshman Estrada, college is far into the future. But that doesn’t stop her from dreaming. “I want to go to a university,” she says. Right now she is thinking about the University of Oregon. Estrada says that thanks to the ELD class, she is now more confident with her English, and hopeful about what the future holds for her.