Last year, Giovanna Bishop felt well prepared for her AP Calculus first semester final exam. She had worked hard and already had a high A in the class. But she knew it wouldn’t hurt to study more when a fellow classmate asked her to help with some extra problems.

Little did she know that the problems they were solving were from the actual final that the classmate, who was a senior, had stolen from their math teacher’s classroom.

Bishop, then in her junior year, wasn’t sure what to think when she found out. “This whole time I had been studying what’s on the test,” she recalls. “I thought ‘Oh great, what are we supposed to do,’ but at the same time I was like ‘OK, I guess it’s kind of like a freebie.’”

When her teacher found Bishop, the test-thief and another student studying the stolen test, Bishop and the other student received an automatic F on the final. The student who stole the test was suspended and got an F in the class.

Cheating. Most students have done it at some point or another in their academic careers. Whether it’s a wandering eye during a math test or important history dates written on the back of a hand, the possibility to cross the lines of academic honesty is always present. Even for the most honest, hardworking students, sometimes all it takes is a stressful week and having your GPA on the line to be tempted.

With current advances in technology, cheating and plagiarizing are becoming easier than ever. Where and how do Grant students draw the line between actually doing the work and faking it?

Bishop says if her teacher hadn’t found out the test was stolen, she probably would have taken the final even though she already knew some of the answers. She says she doesn’t cheat regularly and acknowledges that it’s wrong, but that it can be hard for some students to make the right decision when you get caught up in the culture of cheating.

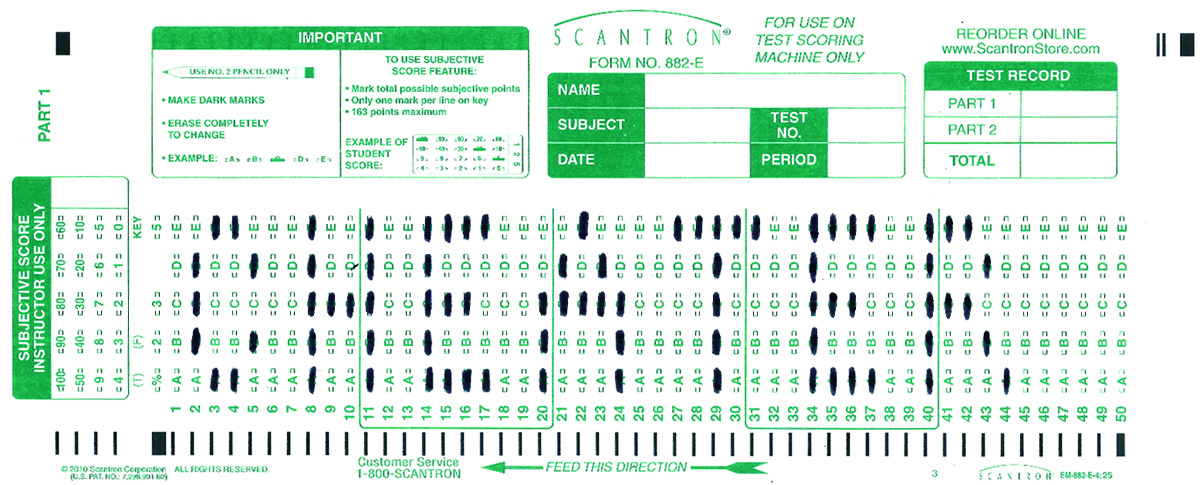

Based on an informal Grant Magazine survey, 96 percent of Grant High School students say they have seen someone cheat or plagiarize at school.

Based on an informal Grant Magazine survey, 96 percent of Grant High School students say they have seen someone cheat or plagiarize at school.

According to David Wangaard – executive director at the School for Ethical Education in Milford, Conn. – in one survey, students were asked if they thought it was morally wrong to cheat, and 60 percent said yes. But when the question was rephrased to ask if it was wrong to cheat on schoolwork, only 40 percent said yes.

When kids are constantly submerged in an academically dishonest environment, adds to the culture that there’s nothing wrong with cheating. When a number of Grant students interviewed were asked about cheating, they responded by inquiring about how broadly do you define the word. Was copying notes that would never be graded cheating? Was collaborating on an assignment or forgetting to cite a source cheating? Different students came to different conclusions, only adding to the already blurred line on what is acceptable.

“It’s something that we just do,” says sophomore Jonzanae Johnson. “You always know that if you don’t have the answers, there’s a friend that you can get the answer from. Everyone knows it’s an option. It’s something we depend on.”

Some of the most common ways students cheat is by copying off each other’s work. Grant history teacher Kevin Alvord says he often sees his freshmen copying out of each other’s notebooks. He says it’s sometimes hard to tell for sure if someone has cheated. But when a kid with an empty notebook suddenly turns in a full, well-written one, he has his suspicions.

Besides copying work, students who cheat write notes on their hands, Google the answers to test questions on their smart phones during tests or plagiarize papers from the Internet.

The honor code of academic honesty has become so lax that if a teacher leaves the room during a test, many students don’t hesitate to turn to their classmates and share answers.

Grant Principal Vivian Orlen acknowledges that cheating and plagiarism is an under-addressed issue at Grant. “We’ve taken for granted that students are doing the right thing and making the right choices, and we’re not spending enough time upfront reminding ourselves of what it means to be an ethical student in the 21st century,” she says.

If Alvord suspects someone of cheating, he confronts the student and gives a warning. He says the conversation usually prevents students from cheating again, but the consequences are higher if they plagiarize or cheat on a test.

Last year, Alvord caught four or five kids who plagiarized an economics essay from the Internet. “That’s pretty serious that they are just willing to go print something out from the Internet and then say, ‘Hey, this is mine. I did this.’”

If a student gets caught and sent to the office, Vice Principal Curtis Wilson says he follows district Public Schools’ policy on cheating. According to the policy, minor and first offenses warrant conferences and interventions with the student. Serious or repeated offenses can lead to a referral, suspension or expulsion from the school.

Wilson usually sees a handful of these cases a year, mostly dealing with students who have plagiarized research papers. But according to Grant Magazine’s survey, of the kids surveyed who had cheated or plagiarized, fewer than 15 percent said they had ever been caught.

Bishop says she felt awful as she sat in Wilson’s office, her notebook full of the test problems she had been solving that she technically would have been able to use on the open note final.

According to Wilson, students who get caught “are embarrassed. They feel guilty. A lot of these kids are academically sound but for some reason they think this is an easier way to keep that grade up.”

“If it’s a first offense, they come down, talk with us, and we find out what was going on and why the person cheated,” says Wilson. Teachers usually give students an automatic zero on a cheated or plagiarized assignment and a referral is logged in their academic record.

Often, students who cheat are the ones who are struggling with the academic concepts. Alvord says in his classes, he often sees kids cheating not to get an A, but so they don’t flunk. He credits a “more for nothing” type of mentality in teenagers today as one of the culprits, and says some kids think: “Fine. If I learned nothing and got a B, I’m okay with that.”

Another reason kids cheat is that a lack of respect for the teacher can cause students to not care about their work. When kids have a good teacher who is passionate about a subject and the education of their students, they will feel more willing to put in their own time and effort.

But these days, even some above-average students are taking the shortcuts.

Sophomore Annie Willis points to the pressure put on students to succeed as the driving force to why people cheat. “The pressure to not fail, the pressure to get an A and get into a good college and get a scholarship really does diminish the actual learning because we are more concerned about getting the A rather than actually understanding the subject,” she says.

Junior Kiah Stern admits she falls victim to this system. “I freak out when my grade is going down, even if I have a 90.1% I’m like, ‘I’m going to fail!’”

Sara Onitsuka, a junior, points out that a C is supposed to be average. “But I mean, how many good colleges can you go to if you have a 2.0 GPA? Even a 3.0 is kind of bare minimum,” she says.

Even though Willis, Stern and Onitsuka all agree they have seen many of their classmates cheat, they say they would never tell on them.

“I can’t imagine anyone ever going up to a teacher and being like, ‘This person’s cheating,’” says Willis. “Automatically, you would labeled.”

This only cultivates the culture that cheating is OK and that there are no repercussions. So who isn’t cheating? Wangaard says it’s usually fewer than 10 percent of students. He says the difference between the 10 percent and everyone else is that these students deeply view cheating as morally wrong, a belief that may come from faith, family or a strong moral compass.

In Leah Kirschner’s English classes at Grant, every year she teaches about plagiarism, a lesson many of her students say discourages them from trying it in the first place—or they at least feel bad if they try to cheat in her class.

Kirschner helps her classes understand plagiarism, what it looks like and the consequences. Orlen says this is an important conversation that all teachers should be having with their students—many of whom may not even know that what they are doing is considered plagiarizing.

Even with these precautions, Kirschner sees kids using the copy-and-paste tools. “I can see it in students who all of a sudden their writing skills become very advanced or there is a variance of style within one paper,” she says. “Do I always catch it? Probably not.”

This year at Grant, cheating and plagiarism has come to the forefront for some Grant teachers. Kirschner is part of a group of staff starting a discussion about how to reverse the culture of cheating. “Students think it’s OK,” she says. “The only regret they have is getting caught.”

She agrees with students that there is immense pressure to get good grades at all costs, and thinks one of the keys to the solution is taking away the emphasis on the points system. “We want our students to appreciate the learning more than the gathering of points,” she says.

Bishop says students don’t take it seriously. After the incident involving the math test, she wrote her teacher a letter apologizing for what she had done. She says she felt even worse about the whole incident because she respects the teacher and the class.

“Lesson learned,” says Bishop. “Once you go through something like that you never want to do it again.”