Grant senior Nate Karn remembers a time he was in fifth grade and was hanging out at a friend’s house. They were playing video games over winter break when his father, Scott Karn, walked up to the door. Nate needs to come home, he said. His little brother, Eliott Karn, was in trouble.

“He told me, ‘Your little brother, he is pretty sick,’” Nate Karn recalls. “At that time, I could feel my dad was pretty panicked; he didn’t show it but he just moved quickly through the conversation. I didn’t know that it was a life or death situation until a few years later.”

Eliott Karn, known to his friends and family as Eli, was only five at the time. Doctors diagnosed him with a brain tumor at the base of his skull. The next day he was rushed into a 10-hour surgery to remove the tumor. “It was about as big as a golf ball,” says their mom, Karen Karn.

Eli Karn survived, but he developed a condition called cerebellum mutism; he couldn’t speak, swallow, or walk. And he couldn’t use his arms or legs. The doctors told the family this happens in five percent of cases for people who have this operation. They didn’t know when things would return to normal for him, doctors told the Karn family: “It’s different in every case.”

When Nate Karn found out about his brother’s situation, he was in shock. “It didn’t really hit me until a good five or six days later.” He didn’t understand the seriousness of his brother’s condition until he saw him in the intensive care unit.

It wasn’t the first time the Karns had a child with a medical serious condition. Two weeks before his eighth birthday, Nate Karn starting noticing strange symptoms. “I just remember being so thirsty all the time,” Karn recalls. “I would be going to the water fountain so much during class.” He got very thin and was exhausted all the time.

Then his family found out that his body had run out of insulin, meaning that he had diabetes – a punishing disease, especially for a young child. The body needs insulin to break down sugars and store energy.

Diabetes comes in two forms, Type I and Type II. In Type I cases, people are usually born with the condition. About 10 percent of cases are Type I, doctors say. Type II diabetes is usually caused by unhealthy habits, like eating unhealthily or not exercising.

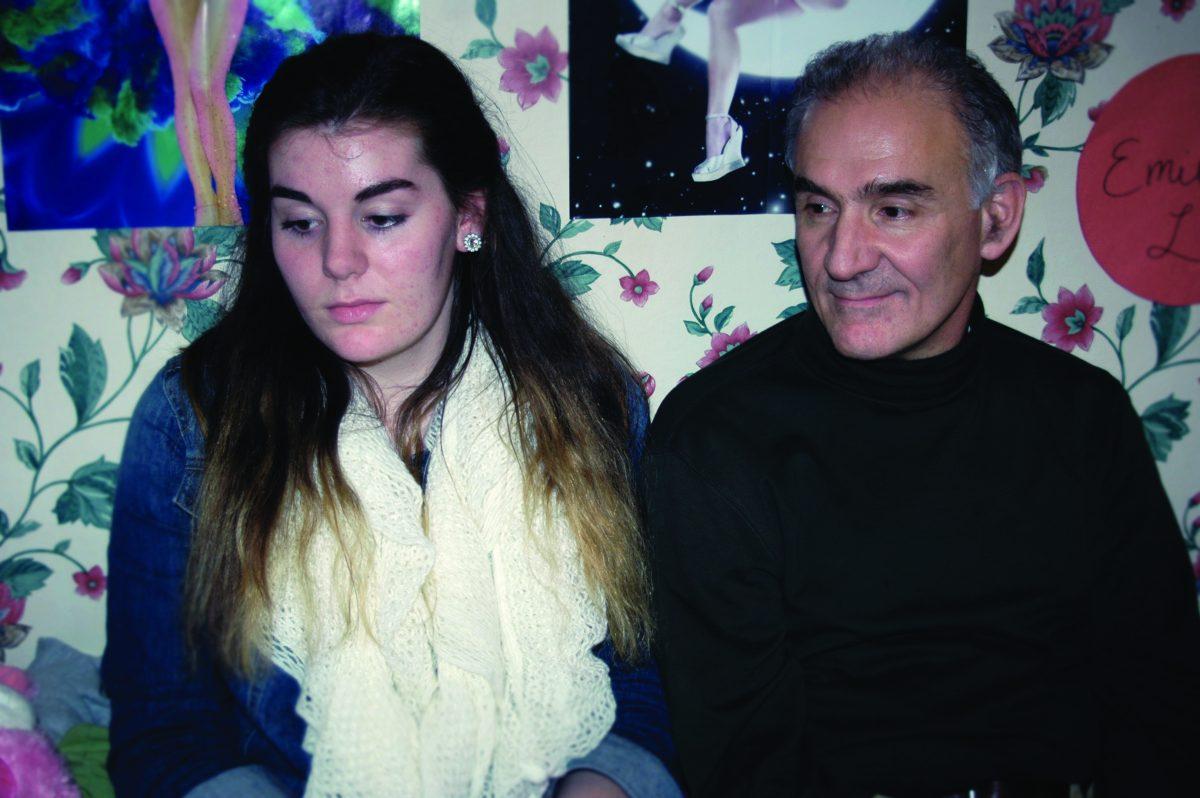

It’s not uncommon to hear about families with a child struggling with a medical condition. But having two siblings facing the reality of a lifetime battle can be a sobering experience. “It is important to get support for the family,” says Robert Finkelman, a licensed professional counselor and family therapist. “It is important for the parents to have enough of [an] adjustment before they can work as a family again.”

Nate and Eli Karn, today 17 and 12, have turned their experiences facing adversity into something more. And with the help of loving parents, they have learned from each other as they have grown. As frantic as their lives can be sometimes, they are bonded by what makes them stronger: their brotherhood and their life struggles.

In the spring of 1982, college student Karen Karn needed a typewriter; through a mutual friend she borrowed Scott Karn’s. When she returned it full of candy, she caught the eye of the Dustin Hoffman-looking college kid. After years of dating they married on July 24, 1987 and lived in the Bay Area for seven years.

When their oldest boy, Phillip, was born in 1992, they decided to move to Portland the next year. Nate Karn was born the year after they moved to Portland, and Eli Karn came along six years later.

Growing up in the Karn household, the three boys were always active: playing Little League baseball, going putt-putt golfing, and running around with the other neighborhood kids. Their house grew as they did: redoing the basement, adding on rooms, and finally getting enough furniture to fill up their house. These things changed when Nate Karn was diagnosed with diabetes, but it got even more hectic when Eli Karn was diagnosed with his tumor.

After the surgery in 2005, the family pressed ahead. Eli Karn went through chemotherapy, radiation, and had a feeding tube. He had to learn how to walk and talk again. The tumor shrunk and things were okay for a while. The small chunk of tumor left in his brain from the first surgery had to be removed, though, by stereotactic radiation. He lost his ability to walk again; he was in a wheelchair for two years after that.

Today, he has balance problems and has to use a walker. For months, Eli’s parents had to take care of him, trading off going to the hospital and staying at home. This left only one parent at the house to take care of the older boys. “A lot of times [my childhood] was skipped over. I had to be independent. My parents couldn’t be at home all of the time, which isn’t typical,” Nate Karn says.

These days, the Karns have settled down to a “new normal.”

Nate Karn continues to manage his diabetes. He has an insulin pump that injects him with insulin every hour on the hour. At lunchtime, it’s not uncommon to see him pull out a meter and test his blood sugar.

Eli Karn’s disabilities affect his academic work: his eyes have trouble tracking and reading is a challenge. He also has problems with fine-motor skills because the nerves in his brain don’t fully connect to his fingers, making writing difficult for him.

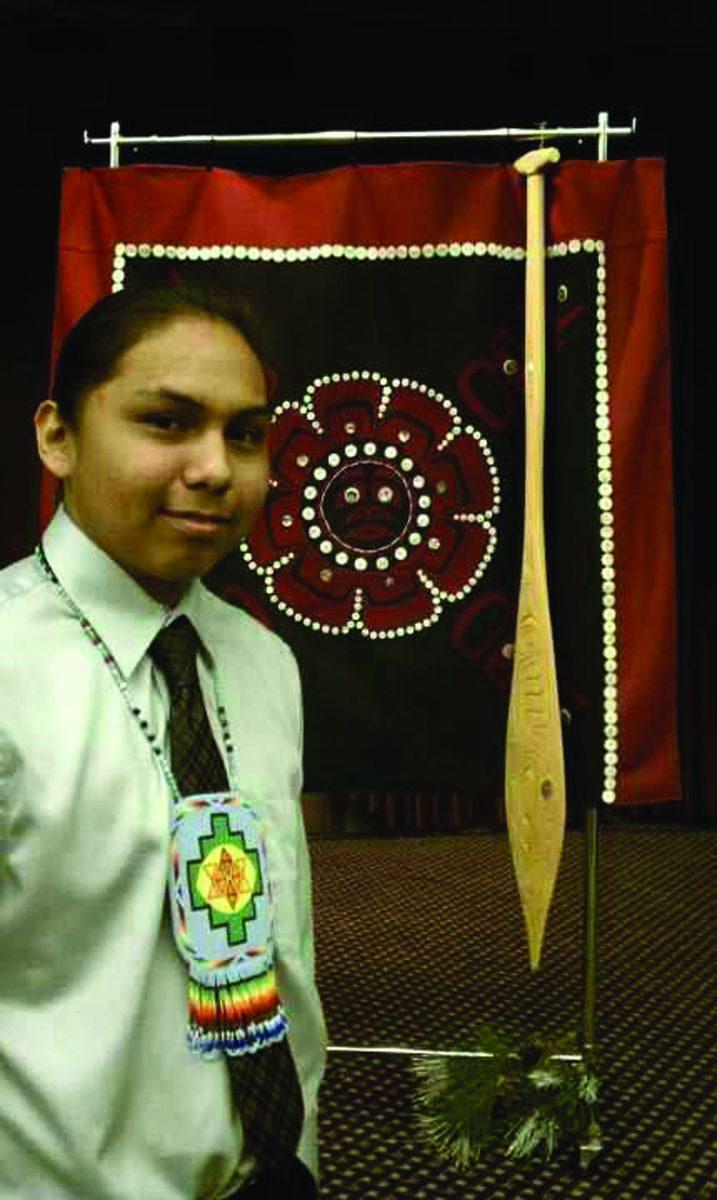

As hard as it is now, it makes it harder sometimes that he remembers what it was like before he had the tumor. Walking, playing baseball and soccer are the activities he misses the most. Though his disabilities limit him, Karn has worked around them and found a new passion: painting. He strives to improve as he grows his artistic talent at Da Vinci Middle School. “I want to be an inspiration for others,” he says.

The Karn boys are just like any set of brothers; they roughhouse, they bicker, they argue and call each other names. Phillip Karn attends Gonzaga University, where he studies. At home, the brothers turn on the TV show “Avatar: the Last Airbender” and grab some snacks before they have to start their homework.

When asked if he loves his brothers, Eli Karn keeps it hidden. “I can’t say it I because it will ruin my job: being funny,” he says.

Nate Karn smacks him on the top of his head. “You’re too proud to admit these things, you butt-face,” he says.

Nate Karn isn’t scared to say it. “I think he’s a hero. The fact that [his tumor] never affected his spirit. He’s the same kid he was before he went into surgery: kind of light-hearted and simply carefree,” he says.

As for the parents, they’re glad they still have their boys.

“Not a day goes by that I don’t feel very fortunate, that we have situations that are manageable and that we are able to move forward with our lives,” Scott Karn says. “We are very, very fortunate with both Nate and Eliott.”