Grant High School junior Adair Powers has a 4.0 grade-point average, is junior Site Council representative, and the vice president of the school’s UNICEF Club. Each Wednesday, she takes a four-hour shift volunteering at the Providence Portland Medical Center transfusion unit.

While a number of her male classmates linger in the halls after school chatting up girls or heading home to play the latest video game, Powers is on a mission. She wants to attend a prestigious university and then dive into a humanitarian-based career.

“My homework habits can sometimes be a little obsessive,” Powers says. “I hate having to do homework last minute. I feel like I am cheating myself more than my teachers. We are in the modern world. Women can strive to achieve, so I don’t see why they wouldn’t.”

Sophomore Kyle Chin recently attended a visit with a University of Southern California recruiter. He’s dreamed of attending USC for most of his life because of its science program and the wide variety of opportunities it offers students. When he walked into the Grant College and Career Center, he found himself surrounded by nine female students. He sunk into his chair as the ambitious girls flipped through informational booklets and peppered the recruiter with questions.

Chin quickly realized that he’ll be judged among an overwhelming number of outstanding female students the moment he applies to college.

Welcome to the high school world of women and boys. These days, unsettling displays of the gender gap – an academic disparity between female and male students – are found at Grant and nationwide.

Madeline Kokes, the coordinator for the College and Career Center, sees more and more students taking advantage of the college visitations and career opportunities she offers in her room. She estimates that about 75 to 80 percent of the students who show up are girls. In fact, of the 173 students who signed up for college visits for the last week of October, 136 were girls, while only 37 were boys.

Although Grant produces plenty of successful girls and boys, the difference in gender performance can be found in nearly every department of the school. This year, the average female accumulative grade-point average among sophomores, juniors, and seniors is 3.25, while the average for boys is 3.04.

In contrast with how Grant boys dominated school-wide activities 30 years ago, girls now make up the majority of participants in student government, National Honor Society and theater. Girls are less likely than boys to drop out, get suspended or run into trouble with teachers and the administration.

“Boys are forgetting how to lead,” says social studies teacher Don Gavitte, who has taught at Grant for 12 years. “No matter how you slice it, the statistics show that boys aren’t doing well. We need to work on that.”

Gavitte has found the ratio of girls to boys in his advanced classes tends to be two to one, while his other classes sit at half and half. He became concerned with this trend nearly a decade ago, after regularly observing many differences among boys and girls in the classroom.

“I see girls working harder,” Gavitte says. “They ask more questions, they work together more and they take advice better.”

Amy Ruona-Banister, an adolescent brain development expert, is the prevention education coordinator for Portland Public Schools. While she avoids making generalizations about the gender gap, she acknowledges the truth behind Gavitte’s observations.

Ruona-Banister says “with 35-40 students in a class, to make sure everybody is engaged and everybody’s learning style is being tapped into is a really hard thing to do.” When asked if this challenge for teachers has more of an impact on male students, she responds: “Definitely.”

There are exceptions to the gender gap. Nyles Green has a 4.0 as a sophomore and maintains a passion for music, math, and science. “I just do the homework, pay attention, and take notes,” Green says.

Regardless, the female competition remains fierce. Grant senior Emma Franke says she has never had a B in her life. School has always been a high priority for her and she feels pressure to extend her education. “I have always been really academically driven,” she says, “I used to ask my parents to give me math books instead of coloring books.”

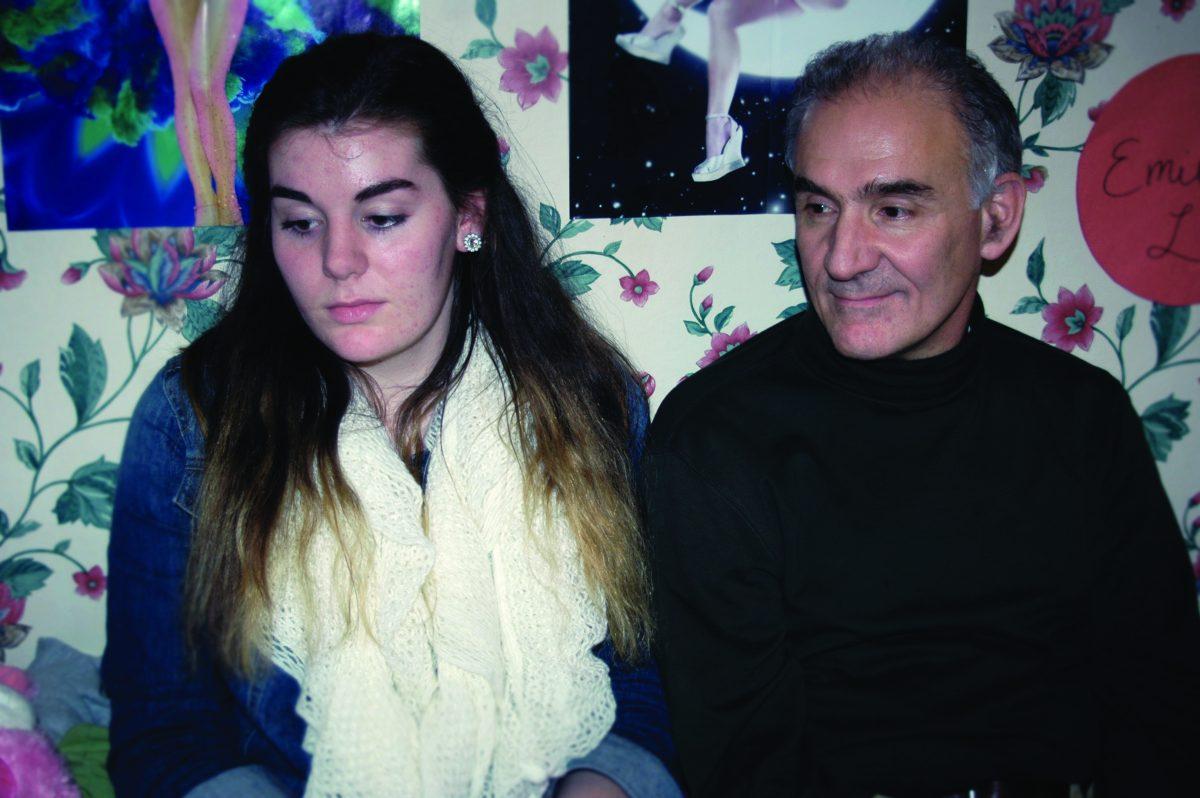

Christine Dean, the mother of a senior girl and a junior boy at Grant, has seen differences in learning styles between her children. Her daughter, Emily Turner, is extremely organized and works on homework meticulously each night, never having to be asked about it. Her brother, Alex Turner, however, would much rather submerge himself in a magazine, and usually needs to be pestered a couple times per evening before he begins his homework.

“Girls listen to the teachers and want to please the teachers,” Dean says. “But boys not so much. If they please their teacher it’s just a byproduct.”

Liz Mahlum, a counselor at Grant, feels the arrangement of the school system itself can make learning especially difficult for boys. Boys often have more trouble sitting still in class and concentrating for extended periods of time. The lack of engagement for many students stems from being placed in crowded classrooms that offer very few opportunities for kinesthetic learning, she says.

“It’s really easy for any student to become disconnected from their learning when they’ve never really felt like it fit them,” Mahlum says.

“It’s really easy for any student to become disconnected from their learning when they’ve never really felt like it fit them,” Mahlum says.

The academic gap between girls and boys at Grant is representative of the rapidly expanding national gap between female students and male students in college admissions. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 1970 the United States undergraduate college enrollment was 57 percent males compared to 43 percent females. Nearly 40 years later in 2009 – the latest figures available – that ratio has completely reversed with women now making up 57 percent of undergraduates.

Robert Street, the assistant director of admissions at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Wash., sees boys entering the college search at a disadvantage. “I don’t think guys are paying attention as much. They aren’t that involved in the actual college search,” says Street, who adds that Whitman’s application pool is 64 percent female and 36 percent male. “Girls tend to be the ones that really do the research, ask the questions and attend the events.”

The gap has its own unintended consequences and poses a threat to high-achieving female students looking to apply to college. According to a U.S. News & World report, “female applicants have faced an admissions rate that averages 13 percentage points lower than that of their male peers just for the sake of keeping that girl-boy balance.”

Maintaining the male-female equilibrium is an issue every college admissions department deals with. Now more than ever, female applicants will need something extra to help them stand out.

Grant seniors Kendall Wynde and Katrina Rapp, female students who excel in the classroom, recognize they belong to a demographic that will make it more difficult for them to be admitted into the colleges of their choice.

“I don’t have anything about me on paper that makes me more appealing,” Wynde says, pointing to socioeconomic class and gender. Because of this, she is motivated to improve her application with factors that she can control inside and outside the classroom.

Rapp, who submitted an early decision application to Pitzer College in California, says, “as frustrating as it is to be admitted at a lower rate, I wouldn’t want to go to a school with 60 percent girls and 40 percent boys.”

However, she adds: “It would be very disappointing to not get into a school because of a boy who hasn’t worked as hard as you.”

As a member of an all-girls unit on Grant’s Constitution Team, Wynde feels her group has an advantage. She says her unit is known for being on top of their work and prepared for class. “I think that it has something to do with that we are all girls,” she says. Although the team is full of high achieving boys and girls, she says: “On average the girls on Con Team are more self motivated to do their work.”

Whitman’s Street attributes the gender disparity to the way classrooms are organized. He says high school teachers “can only deal with one learning style and that’s for the quiet, hard working girl, that can do fine from the back of the room or the front.”

Prashant Dubey is a Portland-area volunteer who interviews an overwhelming number of female applicants for the University of Chicago. He has noticed girls are often more organized, prepared and more likely to meet deadlines. “In K-12 education, I’ve noticed a lot of the emphasis is on organization,” says Dubey. “Girls are fundamentally more organized than boys are and maybe that’s why the dropout rate for boys is higher.”

Mahlum says the constant reduction of alternative elective opportunities has been detrimental to all students, but to boys in particular. Gavitte remembers auto shop as his favorite class in high school.

“We’ve moved away from recognizing and valuing that type of work with this huge push for college for all,” says Mahlum. “But all these other jobs are huge foundations for future careers. It’s a real disservice to a number of people, boys and girls.”

Recently, professional development district-wide has been geared toward closing the achievement gap for minority students. But Grant has wrestled with the gender question, as well.

A few years ago, Grant’s freshman English department responded to the increasing separation between male and female ninth-grade students. “We realized that a lot of our curriculum was geared towards female interest, so we looked specifically for books that would engage teenage boys,” says English teacher Stephanie D’Cruz.

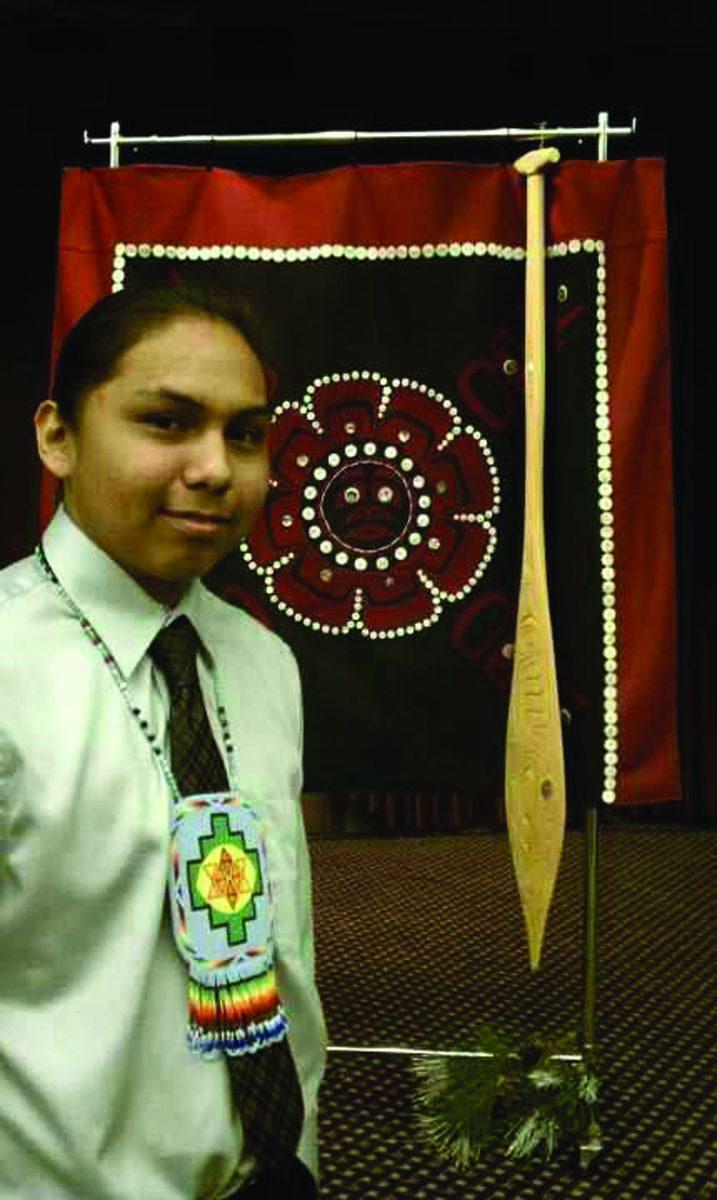

D’Cruz helped modify the freshmen reading list to include “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian,” a witty and humorous story of the struggles of a teenage boy, and “A Long Way Gone,” the journey of a child soldier in Sierra Leone.

While D’Cruz acknowledges that English classes often don’t lend themselves to the hands-on activities many boys crave, she saw a substantial jump in male student engagement with the changes.

Gavitte still worries. The way he sees it? “Boys aren’t growing up, they’re not becoming men,” he says.

But he says “that image of the slacker, ridiculous, forever-14-year-old male” permeating the media should be a call to action for educators. And it should be a signal to any mature young man that they have the opportunity to stand out.